D.A.S.H. Goes to War

The first rotary-wing UAV entered military service in 1962—and remained in operation until 1997.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/in_the_museum_03012012_1_FLASH.jpg)

In hindsight, it was kind of hard to overlook. When we ran our tribute to 100 years of naval aviation (Feb./Mar. 2010), we listed the Fire Scout as the Navy’s first unmanned helicopter.

We were wrong.

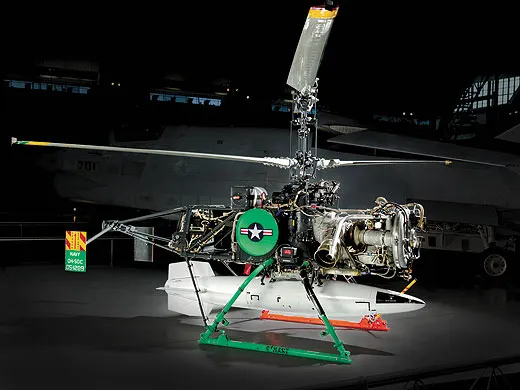

It turns out that the Gyrodyne QH-50 D.A.S.H. (Drone Anti-Submarine Helicopter) was the first rotary-wing unmanned aerial vehicle to enter military service. And this past October, the National Air and Space Museum acquired its own D.A.S.H., when Peter P. Papadakos and his family donated a QH-50C to the collection.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Soviet nuclear-powered submarines began to proliferate. As part of a program to increase anti-submarine coverage, the U.S. Navy brought older destroyers back into service. Unable to fit a full-size helicopter onto the destroyer’s deck, the Navy looked for a solution. The service needed an aircraft armed with a Mk. 57 nuclear depth bomb or two torpedoes that could take out a Soviet submarine before it could come within striking distance of U.S. ships.

For help, the Navy turned to Peter J. Papadakos, the founder of Gyrodyne (and father of Peter P.). The company, along with Hiller Helicopters, had competed in 1953 for a Navy contract to provide a helicopter that could be delivered to downed pilots behind enemy lines. While Gyrodyne’s coaxial Rotorcycle design wasn’t selected, the Navy was interested in using the airframe as an unmanned drone for anti-submarine missions.

The updated design would become the QH-50A, which entered service with the Navy in 1962 and remained in operation until 1997. Most QH-50 deployments consisted of anti-submarine patrols.

A number of the drones were used during the Vietnam War for spotting naval gunfire. The drones’ job was to determine the accuracy of the guns by reporting—with a live TV signal—where the rounds hit so that the aim could be sharpened.

In the anti-submarine role, the QH-50 would start its mission on the flight deck of a destroyer, where it was connected to two umbilical cables: one to start the engine, the other to power the gyroscopes of the flight control system. From the safety of his station, the controller in the Combat Information Center disconnected the two umbilicals. If the umbilicals’ ejection buttons didn’t work, emergency release cables were pulled free by a more limber, lower-ranking crew member. “We became excellent duckers,” recalls Robert Mack, a former engine technician who was present at the donation ceremony and who served aboard the USS Fred T. Berry from 1965 to 1967.

The QH-50 is also unofficially credited as the first UAV to rescue a soldier in combat. “There’s a man who will say categorically that his life was saved by a QH-50,” said Papadakos at the donation ceremony. On a special operations mission during the Vietnam War, this Marine (the military is currently withholding his name) became separated from the rest of his unit. A nearby destroyer dispatched a QH-50 to pick him up. “He climbed on one of the skids and they hauled him back,” says Papadakos.

By the late 1960s, QH-50s were providing real-time surveillance to the military in Vietnam. But by 1971, the Navy cancelled the D.A.S.H. program due to costs; until 1997, spares were used at the Naval Air Weapons Center at China Lake, California, as targets and target-tows.

The legacy of the anti-submarine warfare (ASW) program is mixed, says Roger Connor, the Museum’s vertical-flight curator. “Part of it was a high loss rate due to both electronic malfunctions and operator error,” he says. “Naval aviators also viewed the program as a reckless intrusion onto their turf—or, more literally, their airspace. The program was ahead of its time, both technically and culturally, but its limitations meant that when the ships could support them, manned ASW helicopters were the weapon of choice for the remainder of the 20th century.”

This past December, the Kaman/Lockheed Martin K-Max unmanned helicopters began supplying troops in Afghanistan. “This was an idea that was tested and demonstrated on the QH-50 airframe back in the 1960s,” says Connor. “We’ve really lost a few decades there when we had a remarkable capability on hand, and it’s only now being realized again.”