The Day After D-Day

When the beaches were won, P-47 Thunderbolts were ready to take the air war to the ground.

:focal(2008x1774:2009x1775)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/dc/56dcb429-f066-414e-bab6-d55125ed487d/03s_am2015_49cas-bai-p47raywalshrocketsnormndy6-23-4401069634_194_tml-live.jpg)

In 1943, Nazi Germany controlled almost all of Europe and much of Russia. Less than two years later the regime was in ruin, its leaders dead or imprisoned, its military reduced to scrap. To its commanders, one cause of the catastrophe stood out: the ability of the Allies to exploit their control of the air. Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of all German forces in the West, expressed the exasperation felt by many soldiers when he told his captors, in an overstatement, that air attacks had made it “impossible to bring one single railroad train across the Rhine.”

Key to making Allied airpower so overwhelming was the routine use of Republic’s P-47 Thunderbolt as a swing-role fighter-bomber, sent to take on the Luftwaffe’s pilots and airplanes as well as Germany’s mechanized ground forces. First conceived as a high-altitude interceptor, the Thunderbolt performed so well against German fighters that few expected it to be assigned the ground-attack role in 1943, eight months after its combat debut. But its added skills and great survivability made the P-47 the most significant air weapon in the Allied push into Germany following D-Day. Developing those skills began a few months in advance of the June 6, 1944 Normandy landing.

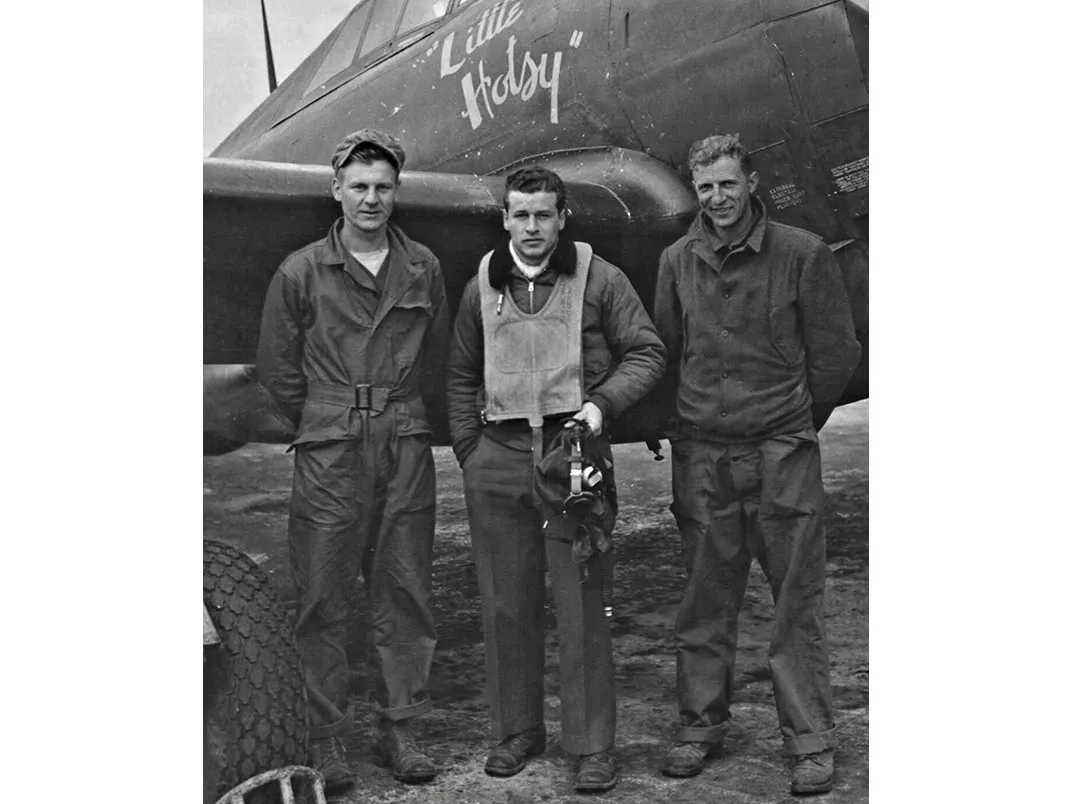

Major Glenn E. Duncan, a rangy, aggressive Texan who would become a triple ace with the 353rd Fighter Group, pioneered using the P-47 to strafe and dive bomb. “Duncan was one of those colorful characters who inspire the rest of us to exceed our perceived limitations,” Norman “Bud” Fortier of the 353rd recalled, “never expecting others to take risks he didn’t take himself.” In March 1944, Duncan persuaded commanders to authorize an operational evaluation of the P-47 as a fast, low-level strafer.

Fighters, half-again as fast as a typical attack airplane, had a degree of speed and agility that made them much more survivable than the light, low-level attack bombers intended for the job. And this fighter had an imposing appearance: Its tail-sitting attitude, wide-stance landing gear, and flat-face radial engine gave it the aggressive look of a bulldog. With a 2,000-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-2800 18-cylinder radial engine, it could fly faster than 400 mph. And it was big. Its porcine fuselage—necessary for housing the complex ducting running from the turbosupercharger to the engine—earned it the nickname “Jug.” The P-47B wing spanned more than 40 feet, and, with an empty weight of more than 9,300 pounds, the fighter was heavier than the Supermarine Spitfire and its U.S. stablemates, the Bell P-39C, Curtiss P-40B, and North American P-51B. Only Kelly Johnson’s distinctive twin-engine P-38 weighed more. The late Donald Lopez, a longtime deputy director of the National Air and Space Museum and a fighter ace who flew P-40s and P-51s during the war, rarely missed an opportunity to joke about the Thunderbolt’s size. In his memoir, he wrote, “the cockpit was so roomy that supposedly, when a pilot was under attack, he could run around the cockpit and yell help every time he passed the radio.”

Duncan found 16 volunteers who devised attack strategies, then took their Jugs down to ground level to test how they performed at strafing. After five successful missions, the pilots returned to their original units to impart their newly acquired experience in low-level attack. In the months before Normandy, P-47s continued to escort bombers on raids deep into occupied Europe and Germany, but once the bombers were safe, they began descending “on the deck” to strafe airfields and find other targets of opportunity before heading home.

***

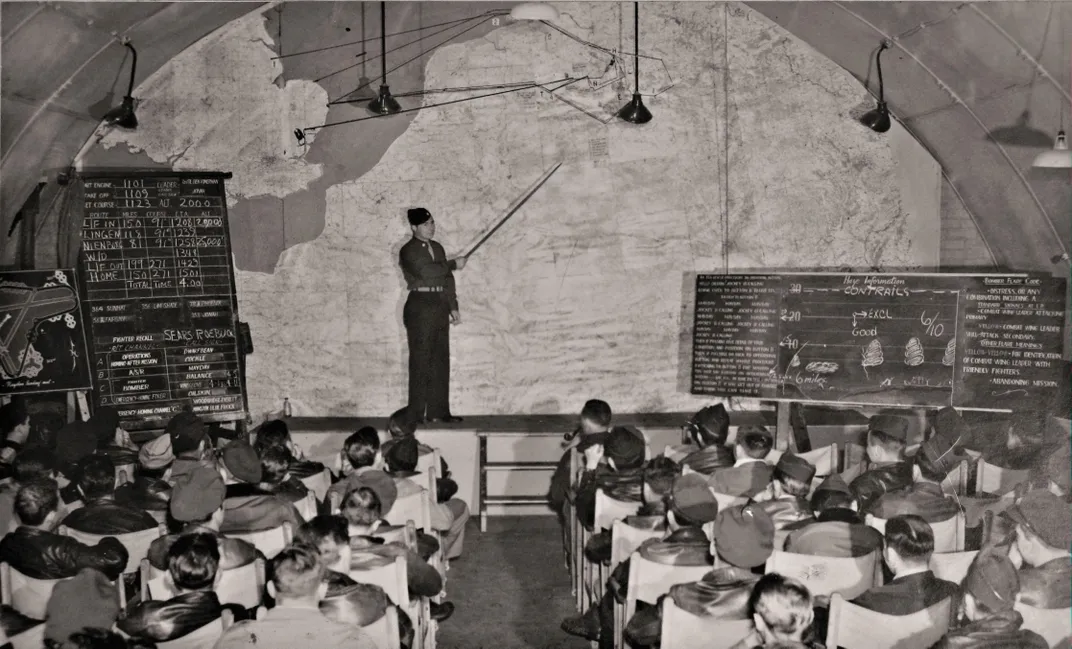

For the ground crews and pilots of the P-47 fighter-bomber groups in the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces, D-Day began well before dawn. The airmen had learned their part in the invasion the day before, and Lieutenant Ernest Stowe wrote in the 50th Fighter Group historical report that “it became apparent that nobody was going to get much sleep.” Pilots, ground crew, and other support personnel “stood by, checking last minute arrangements, maps and time schedules, and drinking great quantities of hot coffee, sweating out take-off time, and the weather.” Finally, at 3:36 a.m., the first Thunderbolts took off. “The sky seemed full of circling lights” as “one P-47 after another, with navigation and dome lights winking,” climbed away, joined up in formation, and then turned toward France.

All day, at any particular moment, hundreds of P-47s were ranging across France and patrolling over the beachhead. Early missions sighted no enemy aircraft and little flak, as the P-47 pilots, enjoying complete air supremacy, marveled at the unfolding invasion. In a typical example, one group watched shell splashes and shore bursts as Allied ships and German coastal batteries exchanged fire.

The German perspective was markedly different. An early morning fog had offered some chance of hiding units on the move, but as it burned off, road convoys and vehicles stood out starkly. Nicolaus von Below, Adolf Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant, recalled that from the outset, “enemy air superiority was clear-cut,” adding: “By that same evening it was already clear the invasion was a success.”

***

June 6 served merely as an introduction to the massive air-ground campaign that followed. The 50th Fighter-Bomber Group’s daily action report of June 8 gives a sense of the pace of activity of the entire Eighth and Ninth Air Force P-47 squadrons in the days after Normandy:

“One squadron...comprised of 16 P47D’s took off on a Dive Bombing mission at 1356 hours 8 June 1944…. Good results were claimed. At [Cerisy-la-Forêt] a tank column of 12 plus was attacked at 1440 hours and many were left burning and demolished. About 30 bombs were dropped on these tanks and they were strafed as well. A direct hit was made on a halftrack at road intersection S of Cerisy La Ford [sic] and left a complete wreck. 18 bombs were dropped on a hutment area near Foret des Biards and area was then strafed.”

U.S. and British combat engineers had landed immediately after the first invaders, and begun scraping and clearing the area to build forward airstrips, the first of which was available for emergency use within a day. These increased the number of sorties fighter-bombers could fly, their on-station duration, and—by eliminating the need for shot-up airplanes to make perilous overwater crossings to get back to British bases—a pilot’s chances of survival if hit.

The Thunderbolts quickly relocated to France. Lieutenant General Elwood “Pete” Quesada recalled, “There was a period of time when we were moving one group every two days.” If saved from ditching, however, Jug pilots were now so close to the fighting that, as Lieutenant Jimmy Wells from the 365th Fighter Group recalled, they “got shot at by rifle or machine gun fire right in the traffic pattern.”

In the advancing armored columns, fighter-bomber pilots were placed in command tanks equipped with air-ground radio. The partnership between airmen and tankers heralded a new mission: “armored column cover,” which transformed the operations of ground forces from blind, incremental progression to informed, speedy breakout. So rapidly did the ground forces advance that by the end of August, even French-based P-47s had to carry drop tanks to ensure they had both the range and the duration on station to meet the needs of the tankers.

America’s most famous armored commander, General George Patton, had warned one fighter commander, “I will go so fast that the Air Forces are going to have a helluva time keeping up with me,” and in the breakout across France, that’s just what happened. In the first month of the advance, Patton’s Third Army moved so far and so quickly that his air support headquarters relocated five times.

The pace of air operations remained intense; on July 29, for example, the three P-47 squadrons of the 50th Fighter-Bomber Group flew a total of 23 missions. At the cost of three aircraft lost to flak and three others damaged, the group’s pilots reported destroying 46 tanks, more than 80 other vehicles, eight horse-drawn guns, “many” buildings, and an anti-aircraft gun, as well as killing an estimated 50 German troops. Altogether, the Wehrmacht lost thousands of tanks, armored cars, mobile artillery, and other transports. Units fortunate enough to withdraw from France did so with few, and in some cases no, mechanized vehicles, returning on foot or by horse-drawn wagon.

A desperate German counterattack in early August, attempting to split the Allied front in two, withered at Mortain, a town close to the Normandy-Brittany border. Intensive British Typhoon and U.S. P-47 attacks, coupled with resolute resistance on the ground, quickly ended the advance. The Panzers made good progress until “Allied fighter-bombers swooped out of the sky,” Generalleutnant Heinrich von Lüttwitz, commander of the Second Panzer Division, recalled morosely.

Daily, fighter-bomber pilots whittled away at the Wehrmacht. On August 8, they claimed the destruction of 47 tanks and 122 other motor vehicles. On August 12, they destroyed or damaged an estimated 350 locomotives and over 3,000 rail cars, transports, and wagons, together with nearly 800 other vehicles and nine oil barges. “It was a big day,” reported Brigadier General Francis H. Griswold, Chief of Staff of the Eighth Fighter Command, “but not unique.”

Just days afterward, over the Falaise-Argentan gap in northern France, the full fury of Allied tactical fighter-bombers fell upon the Wehrmacht as it desperately strove to escape. Destroyed and abandoned vehicles, and the bodies of soldiers and horses, clogged the roads and country lanes. “Appalling scenes took place,” veteran Panzer commander Hans von Luck recalled, adding, “Enemy planes were swooping down uninterruptedly on anything that moved. I could see the mushroom clouds of exploding bombs, burning vehicles, and the wounded, who were picked up by retreating transports.” Jack Dentz, then flying with the 386th Fighter Squadron, had similar memories. “We went in like flying artillery and just destroyed it all,” he told historians Robert Dorr and Thomas Jones, recounted in their book Hell Hawks, adding remorsefully, “It was hideous. It was the only time I actually came home feeling sick. I killed over 60 horses on just one mission; they had been pulling 88mm guns.”

***

The Ninth Air Force P-47s were particularly influential during attacks on Brest, a German-occupied coastal fortress city, and in forcing the surrender of German troops south of the Loire in August and September 1944. A XIX Tactical Air Command report gives an account of the action at Brest: “In the final phases of the assault, fighter bombers were directed to attack individual houses which were obstructing progress of the ground attack—in effect street fighting with P-47s.” So feared were Allied fighter-bombers that Generalmajor Botho Elster surrendered his entire command of 20,000 troops to the advancing Americans, and at the surrender ceremony, he pointedly surrendered not to the Ninth Army’s general but to the general’s Army Air Forces representative.

***

P-47s were, of course, active in America’s other combat theaters. During the Italian campaign, 12th and 15th Air Force P-47s flew on Operation Strangle, an air campaign to interdict German supply lines. In June 1944, 12th Air Force P-47s even took on Axis shipping, dive-bombing and crippling the ex-Italian aircraft carrier Aquila at its dock in Genoa harbor.

On August 15, the Allies launched the invasion of southern France. As with Normandy, Allied airmen had worked out their targets weeks before the invasion—in this case, airfields, roads, and rail lines. On August 28, Captain William B. Colgan was leading a flight of three P-47s up the Rhône River valley when he spotted a long column of vehicles heading north. It measured fully 30 miles long, with many vehicles proceeding two, and even three, abreast.

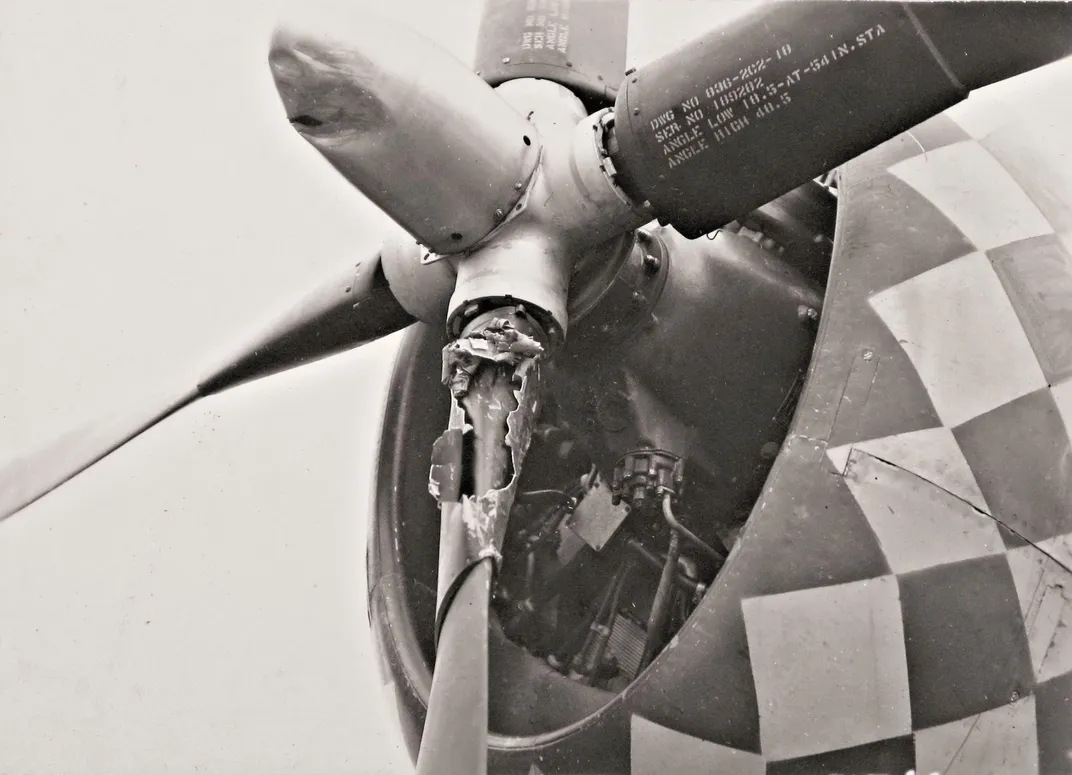

When the three P-47s attacked, a storm of light flak greeted them. They pressed on, destroying and damaging several vehicles and bringing the column to a halt. All three were badly shot up, and two crashed. “Strafing was tougher shooting than air-to-air,” Colgan recalled at a veteran’s reunion over seven decades later, adding “20mm light flak was a killer.” One pilot died, but the other who had crashed hid in a vineyard and then, sheltered by French farmers, made his way to safety.

Colgan’s own P-47 took a hit in the right wing that blew out two of its guns and the ammunition bay, leaving it in a vertical bank, followed by another punishing hit that damaged the engine and caused a serious oil leak. Prepared to bail out, Colgan was amazed that the badly damaged Pratt & Whitney R-2800 continued to run, and even more that the landing gear functioned, enabling him to land safely back at base, though his airplane was beyond repair.

The three airmen’s attack had bought time for another flight of four P-47s to arrive, and over several days of multiple air attacks, the entire column was destroyed. Altogether, the U.S. Seventh Army reported more than 2,000 vehicles of all sorts littering the route.

***

Though its rugged structure and R-2800 engine gave the P-47 a degree of survivability unmatched by sleeker thoroughbreds with inline liquid-cooled engines, such as the P-38 and P-51, it was not invulnerable, and many fell to anti-

aircraft fire. Others were lost when their pilots became fixated and flew into their targets, or flew too low and struck trees or the ground, or flew through their own bomb blast or the explosion of their victims.

Pilots had to balance the value of the target against the danger that could take them and their airplane out of the fight. “The target should be worth what you have to pay,” Lieutenant Colonel Ben Rimerman of the 353rd Fighter Group warned fellow airmen, “meaning that it is foolish to lead a flight across a heavily defended airdrome to shoot up an old beat-down Fieseler Storch [a light observation and liaison aircraft] if that is all you can see.” Airfield attacks that went awry caused several leading Thunderbolt pilots to be lost or taken as prisoners of war, notably Francis “Gabby” Gabreski, the Army Air Forces’ leading ace in the European theater, with 28 victories—all in P-47s. On July 20, 1944, flying a bubble-top P-47D, Gabreski mushed into the ground on a low strafing run against some Heinkel He 111 bombers. He bellied the airplane in and was taken prisoner.

Over the length of its European campaign, the XIX Tactical Air Command lost nearly 600 pilots, either killed or missing in action—an average of more than two per day. Over the summer of 1944, the Ninth Air Force lost nearly 23 percent of its fighter force each month, an average of 227 fighters, the vast majority to flak and small arms fire. One reason for the high losses is the extraordinary number of sorties flown. For every 100 sorties, one Thunderbolt was lost.

***

On December 16, 1944, the Nazi high command launched an offensive through the snow-filled woods of the Ardennes. Known as the Battle of the Bulge, the attack was planned by Hitler and his senior generals for winter, when the weather would prevent the Allies from using their crushing airpower.

Though weather did constrain Allied operations, famously causing Patton to summon his command chaplain to write a “weather prayer,” the airmen flew whenever a chance existed of getting aloft, spotting a target, and getting back.

The Bulge offensive marked the last gasp of the Luftwaffe, which having been husbanded for one last push, proved it could still bite the unwary.

On January 1, 1945, nearly 1,000 German fighters and bombers undertook a surprise strike against Allied airfields on the Continent. More than 200 Allied aircraft were lost, including numerous P-47s. But the industrial behemoth that was the Allied aircraft industry could easily draw on existing stocks to replace any of those lost, while more than 300 German fighters had been shot down, with nearly all their pilots out of action. Fighter General Adolf Galland wrote: “The Luftwaffe received its death-blow at the Ardennes.”

In the wake of the failed Ardennes offensive, the Allied armies continued their advance into the heartland of the Reich. As the armies pushed forward, village by village, they confronted dogged resistance. Consequently, for the P-47s, the war became a remorseless one of bombing and strafing any likely source of opposition.

By March, the Thunderbolts carried fewer bombs and relied instead on the power of .50-caliber strafing against cars, trucks, and other light craft. One such strike, on the road to Bad Durkheim, caused a U.S. Army Air Forces observer to write: “It is so enormous that the mind cannot measure it! The only impression made is that this is the acme and ultimate of death, destruction, and chaos.”

The Hitler regime collapsed into surrender at one minute past midnight on May 9, 1945. The airmen behind the P-47 had fought a hard and costly war. Republic and Curtiss produced 15,683 of the big fighters, of which fully a third—5,222—were lost in combat.