Deadstick Landings

Brace for impact! Unless you’re the pilot!

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11E_DJ10-flash.jpg)

It's a bit of a mystery how the aeronautical lexicon came to include "deadstick." When the engine goes dead, the control stick remains effective. The word emerged from Britain's Royal Air Force during World War I, so one guess is that in the era of wooden propellers, an engine failure reduced the propeller's usefulness to that of a dead stick.

During the war, engine reliability was so poor that pilot recruits had to prepare for the likelihood—not just the possibility—that an engine would quit. They were taught to land within a 150-foot-diameter circle with the engine off. Today, engines are so reliable that most pilots will never have to make a forced landing; nevertheless, in flight training, engine-out procedures are still standard. To prevent a simulated emergency from turning into a real one should the engine fail to restart, instructors simply pull the throttle to idle and direct students to set up an approach to a suitable landing site, then add power before touching tires to ground.

Still, deadstick landings do happen. If an aircraft loses power, a useful number to know is the aircraft's glide ratio: the ratio of horizontal distance traveled to vertical distance descended. Say, for instance, a paper airplane travels 30 feet for every five feet it falls. Its glide ratio—30 divided by 5—is 6.

Modern glider: 70

Hang glider: 15

Boeing 767: 12

Space shuttle orbiter during approach: 4.5

Human body: 1

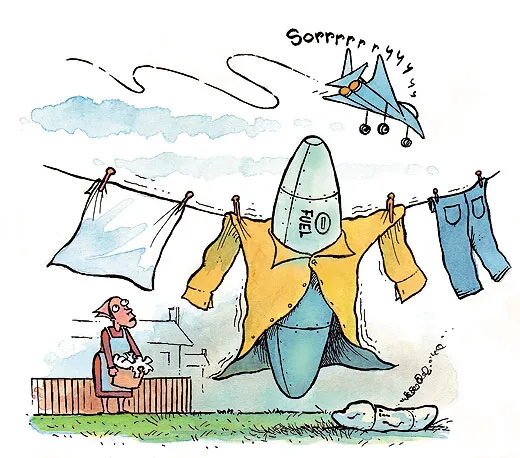

Least Graceful Deadstick Landing

Agricultural pilot Boyd Morgan was flying over pasture land along a ridge near his home in Belgrade, Montana, in 1982 when the engine on his Cessna Husky quit. Barely 20 feet off the ground, Morgan didn't have a lot of options. Pushing the nose down to preserve airspeed, he headed straight for the trees, aiming for a spot between them so that the wings, rather than the cockpit, would bear the brunt of the impact. Then the wind shifted. The airplane stalled and cartwheeled. Morgan ended up upside down about six feet off the ground, hanging by his shoulder straps. He got his seat belt unfastened, but as he fell through the open cockpit door, the door handle caught his pants, pulling them around his ankles. Other than a wrecked airplane and injured dignity, Morgan came away relatively unscathed. "It wasn't funny then," he says, "but I can laugh about it now."

Most Graceful Deadstick Landing

The legendary Bob Hoover designed an entire airshow routine around a deadstick landing. Adapting a training exhibition he did for pilots learning to fly the twin-engine Lockheed P-38, Hoover flew a twin-engine Rockwell Shrike Commander, a business aircraft never designed for aerobatics, in a performance that culminated with a low-level, high-speed pass in which he shut down both engines; did a loop, an eight-point hesitation roll, and a 180-degree turn; "danced" the Shrike down the runway, touching the left landing gear to the pavement and then the right; and finally coasted to a stop at show center. Hoover called it the energy management maneuver—converting potential energy (altitude) to kinetic energy (airspeed) and back—and dedicated it to another Rockwell product, the space shuttle, which also glides to a landing without power.

Best Ditching

(Deadstick Landing on Water)

The most famous example in recent years: After a US Airways Airbus A320's engines ingested Canada geese and shut down last January, Chesley Sullenberger and copilot Jeffrey Skiles set the aircraft down in New York City's Hudson River. All 155 passengers and crew members evacuated onto the wings and were quickly retrieved by watercraft.

Most Embarrassing Ditching

In February 1994, Alan Clark took off in his twin-engine Piper Seneca from Springfield, Kentucky, bound for Crossville, Tennessee, a hop of less than an hour. Clark awoke five hours later, in the dark and over water. He radioed a mayday, reporting that he was running out of fuel. Air Force and Coast Guard aircraft patrolling the Gulf of Mexico found Clark 210 miles south of Panama City, Florida, and led him toward the closest airport. Clark was about 70 miles west of St. Petersburg when both engines quit from fuel exhaustion. Clark ditched the airplane, and a Coast Guard helicopter plucked him from the water, uninjured. In its summary report, the National Transportation Safety Board cited "the pilot's physiological condition (failure to remain awake)" as a significant contribution to the accident. The airplane sank and was not recovered.

Most Frequent Deadstick Landings

For glider pilots, every landing is deadstick. Like Bob Hoover (a glider pilot himself), glider pilots also employ energy management to stay aloft. But even without the advantage of a glider's light weight and high glide ratio, any airplane with sufficient altitude should be able to glide to a safe landing.

Deadstick Landing That Saved the Most Lives

Due to a leak in a fuel line to the right engine, Air Transat Flight 236, an Airbus A330 carrying 306 people from Toronto, Canada, to Lisbon, Portugal, in August 2001, ran out of fuel over the Atlantic Ocean. After discovering that fuel was low, captain Robert Piché declared an emergency and diverted to Lajes Air Base in the Azores, but at 39,000 feet and 150 miles out, the right engine quit. Thirteen minutes later, the left engine followed suit. Relying on a ram air turbine to supply limited power to hydraulic and electrical systems, Piché guided the airliner to the runway. Crossing the runway threshold at 230 mph, 70 mph faster than recommended, the airplane used three-quarters of the 10,000 feet of concrete to bounce, then screech to a halt. Fourteen passengers and two crew members were injured during the evacuation. Piché's reward: partial blame for, among other things, not recognizing the problem sooner.

All About Autorotation

When a helicopter engine quits, the aircraft "autorotates": The rotor blades spin freely in the wind. Using a combination of the cyclic control stick, the collective, which controls the pitch of the blades, and the pedals controlling the tail rotor, a pilot can alter the speed of the spinning blades, and by increasing their pitch, somewhat slow the descent for what is hoped will be a soft landing. Roger Stradley, a 62,000-hour commercial pilot who has done a little of everything in aviation—charters, flying and repairing helicopters, aerial agricultural work, firefighting, gliding, flight instruction—says the only time he lost an engine was in a Bell 47 Super G helicopter while doing a magazine photo shoot in the mountains near Big Sky, Montana. He managed to autorotate the Bell onto a highway leading up a mountain canyon, but no sooner had he set down when he saw a propane truck coming at him. "I thought we were goners," Stradley says. But the truck cab just missed the cockpit, and the helicopter blades glanced off the top of the rounded tank. "I was more afraid of telling my wife what happened than of going to the Great Hereafter," he adds.

A Most Unusual Autorotation

Vintage aircraft specialist Andrew King was making a fourth test flight of a rare 1932 Pitcairn PA-18 Autogiro in July 2008 when at 2,000 feet and a mile from the New Castle, Ohio airfield, the fuel pump quit. King was especially well suited to handle the situation. He had trained on a gyroplane, which operates on the same aerodynamic principles as the Autogiro, and had consulted with, among others, the late Steve Pitcairn, son of the aircraft's builder, Harold Pitcairn, and the late Johnny Miller, then 101, who last flew that very aircraft in 1939. Still, King had to determine the flight characteristics of the Pitcairn pretty much by feel. Being close to the airport, "I was in a good spot, relatively speaking," he says. He pitched the nose for what he guessed was the best glide speed and headed for the airfield. The rotor on an Autogiro spins freely, always in autorotation, with the spinning rotor providing lift. With the engine out, the drag produced by the aircraft's 40-foot-diameter blade made for a very steep descent, King says. When he got to the airfield, at an altitude of 800 feet, King pulled the control wheel all the way back. Unlike an airplane, King says, with the Autogiro "you can't stall it; you can't spin it, which was the whole safety concept" underlying its design. The Autogiro simply "dropped like a parachute." At about 200 feet, King pushed the stick forward a bit and made a normal landing and rollout of 50 feet.

A Harrowing Deadstick Landing

Air National Guard Captain Chris H. Rose was the fourth in a flight of four F-16s, at 13,000 feet, returning to Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C., in June 1996 from a training mission at a North Carolina bombing range. When he pushed the throttle forward, he heard a loud bang. "I didn't know what it was, but it didn't sound good," he later told a National Guard reporter. "Then the vibration started. The distortion was incredible. The whole airplane was buzzing." Rose immediately turned toward the Elizabeth City Coast Guard air station, but he was above a layer of clouds and could not see the base. His fellow pilots helped direct him, and at 6,000 feet Rose broke out of the clouds and saw the runway. He had to jettison two fuel tanks, empty but still heavy, and he feared they might hit a house in the neighborhoods below (they landed harmlessly in a back yard). Like Piché, he crossed the runway threshold 80 mph faster than usual and used the emergency braking system, taking most of the 7,200-foot runway to stop. Rose's feat won him the Koren Kolligian Jr. Trophy, an Air Force award for meritorious handling of an inflight emergency, and today the cockpit-camera video of his ordeal is a big hit on YouTube.

The Ultimate in Energy Management

The space shuttle's approach to landing begins at 400,000 feet over the Pacific, when the orbiter reenters the discernable atmosphere. At 50,000 feet, about 25 miles from the runway, the flight commander takes control. The orbiter rolls out on final approach at 10,000 feet, eight miles from the runway, at 320 mph in a steep descent with the nose as much as 19 degrees below horizontal, at a descent rate 20 times that of an airliner. At 80 feet, the commander begins to flare, bringing the nose up to slow the descent rate and crossing the threshold at some 220 mph. After touchdown, the drag chute deploys, and the orbiter uses about 8,000 feet to coast to a stop. Time elapsed since the commander took control: about five minutes.

How to Make a Deadstick Landing

William Kershner, author of many volumes on flight instruction, notes in The Student Pilot's Flight Manual: "As one instructor put it, ‘hit the softest, cheapest thing in the area as slowly as possible,' which pretty well covers it."

Tom LeCompte's story on vertigo, "The Disorient Express" (Aug./Sept. 2008), won a 2009 Aerospace Journalist of the Year award.