Aviation’s Most Wanted List

The airplanes and artifacts that museum curators dream of finding.

:focal(1205x185:1206x186)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b0/79/b079d234-8ce2-4f28-806e-c0aa0f39d230/05l_sep2020_earhartnasm-nasm-9a14019_live.jpg)

The task would require nothing short of a miracle. Back in March, a reader asked if we’d ever thought about trying to find Charles Lindbergh’s logbook, which was taken from the Spirit of St. Louis in 1927 after he landed at Le Bourget airfield upon completing his solo, nonstop, transatlantic flight. We should start by compiling a list of everyone who was there—more than 150,000 people—and then contact their families to see if the logbook might be squirreled away in an attic somewhere.

The crowds went wild with joy that day, newspapers reported at the time, rushing Lindbergh and his airplane. “Four days later I still retain bruises,” wrote a New York Times reporter. “The reporters assigned to cover Captain Lindbergh’s arrival will not forget that night,” he continued. “And neither will they forget one of the toughest mobs they ever tackled. The Battle of the Argonne was a simple matter compared to it.”

While locating the famous aviator’s logbook was beyond us, we were inspired to ask aerospace historians, curators, and archivists to identify the elusive aerospace artifacts they would most like to find.

Once you read their answers, you might be inspired to create your own list. If you could find any aerospace artifact, what would it be? Send your answers to [email protected], and we’ll publish some of the responses in the next issue.

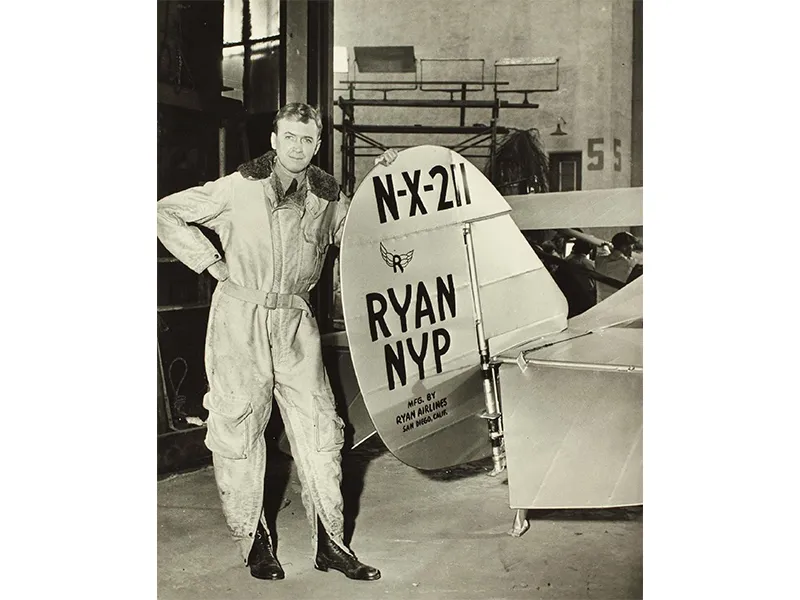

Case of the Missing “R”

“I would like to find the missing winged ‘R’ logo that was cut from the rudder of the Spirit of St. Louis after it landed,” says National Air and Space Museum curator Robert van der Linden, who wrote about his obsession in a 2014 blog post. Before Lindbergh’s aircraft could be moved to safety, “souvenir hunters had grabbed at the aircraft tearing off pieces of fabric from the wings, fuselage, and tail. The French Air Force managed to move the Spirit to a nearby hangar where they patched the wings and replaced the fuselage fabric. They also replaced a small piece of fabric that had been removed from the right side of the rudder. One spectator cut out the winged ‘R’ insignia of Ryan Airlines, the manufacturer of the Spirit, and took it home. To this day, you will notice the winged ‘R’ on the left side of the rudder, and the blank patch on the right [above].”

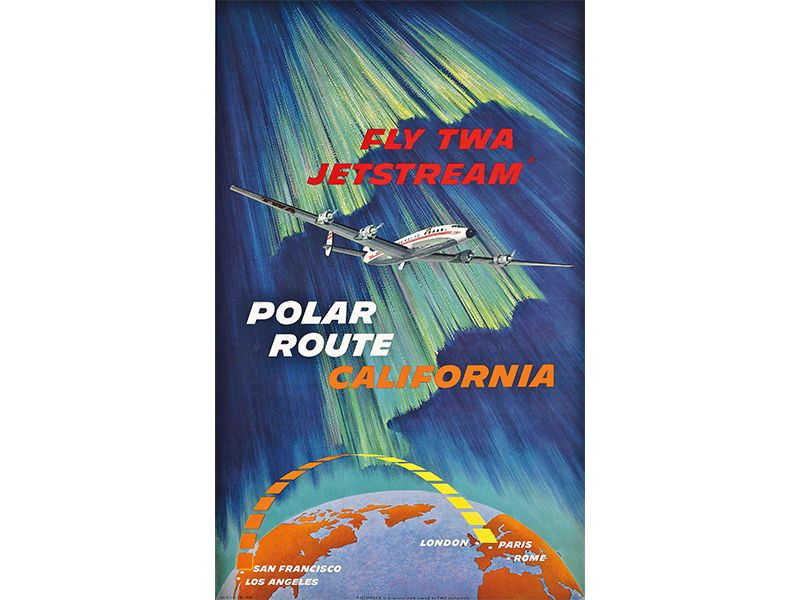

The Polar Express

“I wish we could have the Lockheed Constellation that made the polar flight from London to San Francisco nonstop in 23 hours in 1957,” says Wayne Hammer, a volunteer at the TWA Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. “It should be preserved exactly as it was on that day. Same engines, same cockpit, same cabin. Not renovated or refurbished. Frozen in time after it landed in San Francisco. I’d like to stand next to those propellers that turned for all those hours and sit in those same seats people sat in as they observed the landscape of the extreme northern latitudes of Earth. All in 1957.”

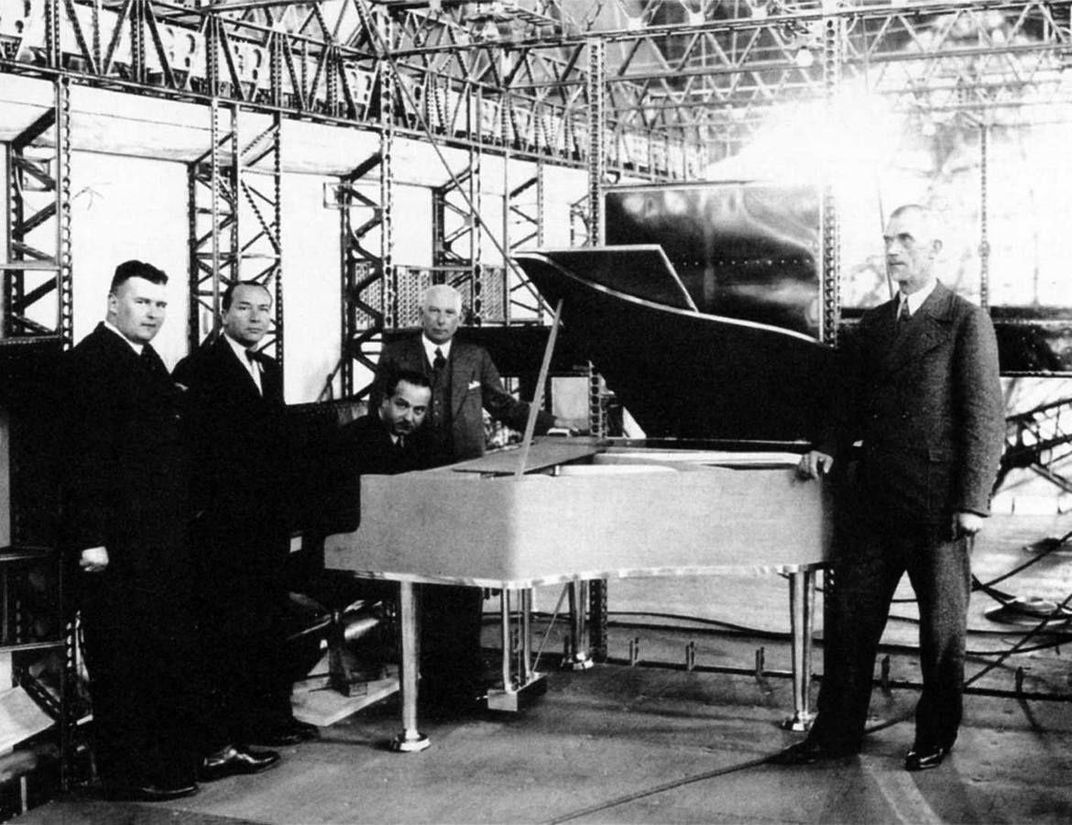

Music in the Clouds

“Blüthner, the Leipzig pianoforte factory, built an aluminum grand piano weighing only 162 kilograms [356 pounds] especially for the Zeppelin [Hindenburg], which, according to one reporter, delighted the passengers with ‘a particularly large and full tone’ despite its metal construction,” says Simone Lipski of the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen, Germany. “On the first trip of the Hindenburg to North America, the Dresden pianist Franz Wagner inaugurated the grand piano, playing works by Chopin, Liszt, Beethoven, and Brahms.” The piano maker’s staff say the instrument was removed from the Hindenburg in 1937 and placed on display in the factory, where it was later destroyed in an air raid. But the Zeppelin Museum has found evidence that the piano was last seen in 1938 in a shipyard crate. And there the trail goes cold.

Profile in Courage

“What I find most tragic is Mildred Doran’s blind courage,” says Dennis Sharp, curator at the SFO Museum in San Francisco, about the only woman to enter the Dole Air Race, the 1927 challenge to fly nonstop from California to Hawaii. “In spite of earlier mechanical problems with the Buhl Air Sedan, Doran, pilot John Pedlar and navigator Vilas Knope took off and headed west over the Pacific. They were never seen again. How close did they get? What happened? We will never know until the wreckage of the plane is found and recovered.”

Hope Floats

In 1933, the Seversky SEV-3 was the world’s fastest amphibian and the first aircraft built by the Seversky Aircraft Company on Long Island, says Josh Stoff, curator at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, New York. “Only one was built and it was sold to the Spanish Republican Air Force in 1936. It was shipped to Spain, then disappeared during the Spanish Civil War. Could it still be in Spain somewhere?”

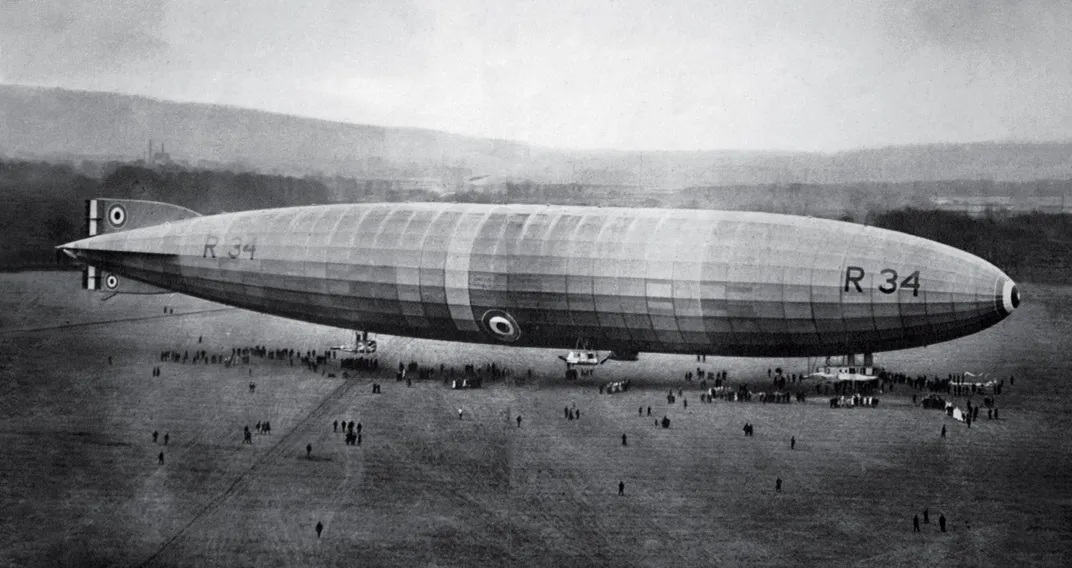

Nickname? “Tiny”

“We have pieces of the mammoth R.34 airship in our collections: fabric, structure, and gas valves as well as lots of photographs, but nothing gives a sense of scale like a complete example,” says Ian Brown, assistant curator of aviation at Scotland’s National Museum of Flight. “None of the great airships from between the wars have survived, but they would be an impressive sight now, and we would love one for the museum.”

Animating Space

“I’d love any of the spacecraft models used by Wernher von Braun in any of the 1955 Disneyland episodes, particularly the intricate and fanciful three-stage rocket in the episode Man in Space,” says Ben Page of the EAA Aviation Museum. An estimated 40 million viewers saw the episode on TV and, later, in theaters. “In those models, I see a moment where the space program was really ‘sold’ to Americans, taking full advantage of the communication medium of the day.”

Reap the Whirlwind

“I would love to find a Westland Whirlwind fighter,” says Rebecca Harding, head of technological objects at the Imperial War Museum. (No interest in the Whirlwind helicopter.) “It was the first twin-engine, single-seater fighter to enter service with the Royal Air Force, back in 1938. Although a relatively successful aircraft and generally liked by pilots, just over 100 were produced, and production was halted when Rolls-Royce, who were responsible for the Whirlwind’s Peregrine engine, chose to focus on the rather better-known Merlin engine. So, ultimately the Whirlwind lost out to the Spitfire.”

Test Tube

“Historically accurate North American F-100 Super Sabres have a very distinctive pitot tube mounted under the aircraft and forward of the cockpit,” says Rod Bengston, a curator with the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum in Hawaii. “Our F-100 came with a homemade copy. One would think that pitot tubes in reasonable condition would be more or less available. Although our jet now has little use for any measurement of its airspeed, its silhouette would be far more accurate if it had a proper pitot tube. I have been offered ‘authentic plans,’ for fabricating a pitot tube, and had conversations with individuals claiming to have seen this object under a pile of debris in a remote airfield. But all to no avail.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/9e/2d9e1a53-586f-4bb1-a930-cdbef46a71b2/05k_sep2020_f100pitota24788_live.jpg)

Queen of the Sky and Sea

They would come to epitomize the romance of flight during the inter-war period, but only 12 Boeing 314 Clippers were built, and none remain, the fleet either destroyed, canibalized for parts, or deliberately sunk. “It was a very elegant way of flying,” says National Air and Space Museum archivist Brian Nicklas. “If you were even more posh than a first-class cabin on a steamship, you flew on a -314 to Hawaii or to China.” The enormous flying boat, says Nicklas, is used even today in movies—think Indiana Jones—to illustrate luxury and point-to-point travel on a map. “If it’s over the water,” says Nicklas, “it’s either a Martin M-130 or a -314 Clipper.”

Part of the demise of long-range flying boats is due to logistics and economy, says Nicklas. “In many ways, paved runways are far easier to deal with than docks.”

Could the submerged hulks of the China Clipper, which crashed in the Caribbean, and the Cape Town Clipper, which the U.S. Coast Guard sank in the Atlantic, be recovered and restored one day?

Start of Something Good

“The original, unaltered prototype Spitfire, K5054, as it appeared in 1936, was the progenitor of one of the most beautiful and symbolic families of flying machines, but still showed its roots in the Schneider Cup racers of the early 1930s,” says Ben Page, of the EAA Museum. “The test pilot is supposed to have said after landing, ‘I don’t want anything touched.’ Hindsight is 20/20, but oh, if only people at the time had listened. A bit of bias here—if somewhere K5054 existed it would be a companion of sorts to our XP-51.”

Beatlemania Begins

“When the Beatles landed in New York on a Pan American World Airways Boeing 707 for their first American tour in February 1964,” says Tomohiko Aono, the aviation collection registrar at the SFO Museum, “the band’s famous descent from the jet’s ramp stairway was immortalized in photographs. Pan Am’s blue globe logo appears prominently at the top of the steps. What happened to this ramp vehicle, and were any components from its famous appearance saved?”

Pan Am was the first to operate the 707—the first U.S. commercial jetliner—and had been flying the route for only six years. The 707 would transform the passenger experience, and lead to design changes in airport terminals, baggage handling, and food service.

Speed Is Life

“The Republic XF-103 was meant to be a radically advanced all-titanium Mach 3 turbo-ramjet interceptor in the 1950s,” says Josh Stoff, at the Cradle of Aviation Museum on Long Island, New York. The aircraft was one of the first to use titanium in its construction, in hopes of handling the extreme heat of high-speed flight. It also featured an ejection capsule for the pilot, should something go wrong. (The pilot also entered and exited the aircraft through the capsule, which was designed to be lowered and raised on rails.) After continued problems with the titanium construction and the Wright J67 engine, the project was cancelled in 1957.

“The full-scale metal mockup and the prototype,” says Stoff, “were supposedly buried on or near the Republic factory in Farmingdale, Long Island.”

Remember the Heroes

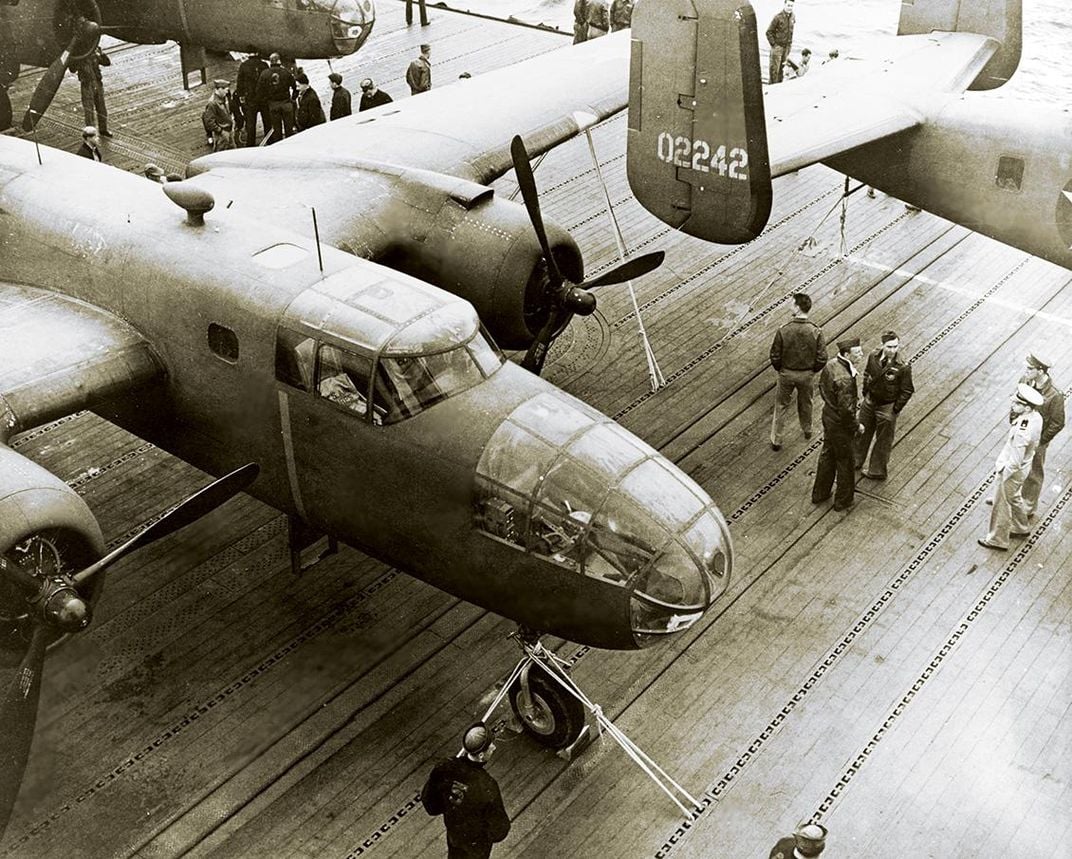

The 16 B-25 Mitchell bombers that were launched from the USS Hornet on April 18, 1942 were supposed to bomb Japan and then continue on to land in China. Fifteen of the B-25s reached their goal, but all crashed. The remaining B-25 landed at Vladivostok in the Soviet Union. While the surviving crew were eventually allowed to “escape” and return to the United States, the aircraft was confiscated.

Wreck hunters have claimed that the aircraft was later used by the Soviets to shuttle mail and military personnel. “From time to time a rumor pops up that the aircraft still exists,” says Chris Henry, programs coordinator at the EAA Museum. “If it did, it would be an amazing tribute to the brave crews who flew one of this nation’s most daring missions.”

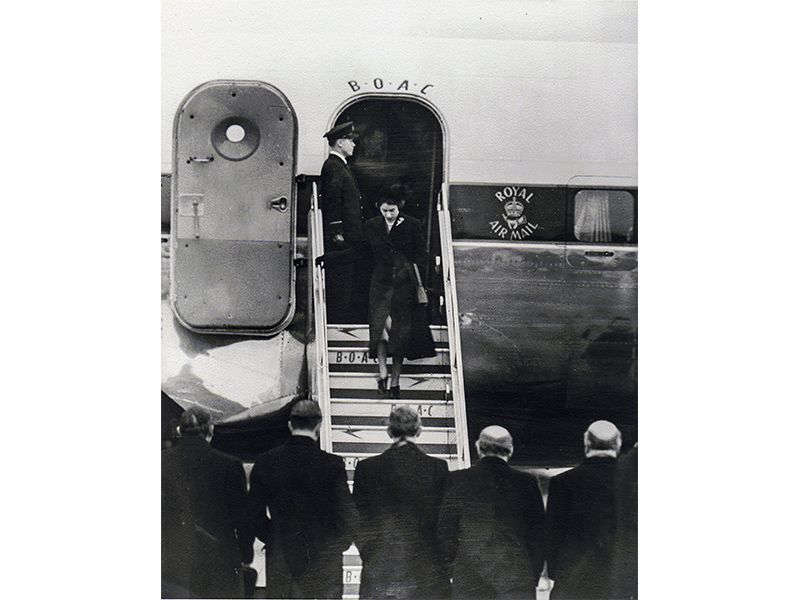

Carrying the Queen

“On January 31, 1952, BOAC, a predecessor of British Airways, flew Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh to Kenya, a royal trip being undertaken on behalf of King George VI, who was unwell,” says Jim Davies, of the British Airways Speedbird Heritage Centre in England. “Just six days later the King died.” The new queen was flown home aboard a Canadair Argonaut named Atalanta. Davies would like to acquire the plaque that BOAC was given royal permission to place in the aircraft.

Looking For Amelia

“We feel like understanding her state of mind after her Electra was damaged on Ford Island puts the world a little closer to understanding her disappearance,” says Rod Bengston from the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum. He is hoping for photographs, correspondence, or references to Earhart’s ground loop in 1937 on Ford Island. Amelia Earhart’s missing aircraft was on the wish list of several aviation museums—and is still one of the most sought-after artifacts in aviation history.