Discarding Shuttle: The Hidden Cost

A symposium entitled “U.S. Human Spaceflight: Continuity and Stability” was held at Rice University’s James A. Baker Institute of Public Policy

On February 15, 2011 a symposium entitled “U.S. Human Spaceflight: Continuity and Stability” was held at Rice University’s James A. Baker Institute of Public Policy. Organized by George Abbey, the resident space expert at the Baker Institute, one might have suspected that it would be Shuttle-centric and indeed, it was. Many pertinent points relevant to the current discussion about NASA’s human space program and its future (or lack thereof) came out of the presentations at this symposium.

The program featured several speakers, all of whom played major roles in the Shuttle program. I found comments by Robert F. “Bob” Thompson most interesting. Bob Thompson is one of the true “old guard” – an original member of Bob Gilruth’s Space Task Group at NASA Langley, a group pre-dating the Mercury Program. Thompson was head of the Apollo Applications Program (Skylab) and the first manager of the Space Shuttle program. Many of his remarks resonate strongly with points I have made here and elsewhere about serious problems being dismissed or ignored in the unseemly rush to re-vamp NASA from an operational space flight agency into a check-writing bureaucracy for New Space endeavors.

Thompson’s theme was a considered and educated look at what discarding the country’s Space Shuttle Program means. Both his talk and the talk by Howard DeCastro (Shuttle Program Manager at the United Space Alliance, which operates the Shuttle system for NASA) carefully outlined the history of the Shuttle program and the possibility of flying the Shuttle commercially until a new system becomes available, thereby retaining our national spaceflight capability. They covered the many compromises made both in Shuttle’s conception and in its execution, as well as its unique capabilities. The Shuttle can both deliver and retrieve payloads from space; it is a fully integrated transport and servicing system in low Earth orbit. The famous Hubble Space Telescope would be a useless piece of junk instead of a national treasure without the Shuttle missions that first allowed for the repair of its defective vision and then returned to service the instrument in space multiple times over the ensuing decade.

An often ignored but critically important issue is the supporting infrastructure for spaceflight. Thompson made the analogy that when people see a Shuttle Orbiter, they really are seeing just the “tip of an iceberg.” The Shuttle is more than an orbiter vehicle; it is also the servicing facilities at the Cape that process and prepare the orbiter for launch. It is the ET fabrication facilities at Michoud and the SRB plant at Promontory as well as the Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME) that has performed flawlessly over the 133 flights to date. It is the mobile crawler and the launch towers at Pad 39-A. And it is the trained cadre of people that put all the pieces together and make them work in concert to deliver and return people and equipment from space. Thompson rhetorically encompassed his argument thusly: The Shuttle is a “dumb vehicle that cost too much” but is a “fully functional part of a space transportation system – an 18-wheel, extended cab work vehicle.” He told the audience that Orion, Soyuz and Progress were more like “taxis” and “pickup trucks.” He said that the Constellation vehicles (chosen to implement the 2004 Vision) were bad decisions, followed on now by an even worse decision.

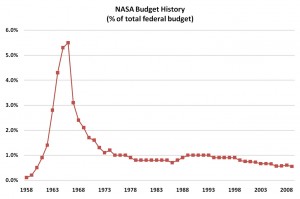

Thompson used a familiar graphic, the chart showing NASA’s fraction of the annual federal budget over decades (see above). The large spike centered around 1966 represents peak spending for the Apollo program. Thompson made two specific observations about this graph. First, Richard Nixon (who took office in 1969) is often damned as the President who “killed Apollo." But the graph shows that the ramp-down in spending for Apollo began two years earlier in 1967, in Lyndon Johnson’s administration. The Vietnam War required some of NASA’s money, so Apollo-Saturn production managers were told to build the equipment needed to fulfill Kennedy’s decadal goal and shut down thereafter.

Additionally, Thompson made the very significant point (one usually ignored by many engaged in space policy debates) that the “Apollo spike” paid for the infrastructure – the buildings, laboratories, test and training facilities, and launch systems – that Apollo used and that the Shuttle uses to this day. By terminating the Shuttle with no follow-on, the fate of most of this infrastructure is the scrap heap. Note that the “Apollo spike” in funding happened forty years ago. To design and build the supporting infrastructure for human spaceflight in the mid-1960s, we annually spent ten times the fraction of the budget that we do now. Given the reality of the nation’s finances, NASA will be lucky if they can continue to get one-half of one percent of federal spending per year. This does not seem to be a good time to throw away three functioning Shuttle orbiters, thereby discarding a working national space faring capability, one carefully built and paid for over the last 50 years.

Several New Space companies are working on vehicle designs, which, if successful in creating a replacement space “work vehicle,” will need their own supporting infrastructure. These efforts will necessitate creating all the facilities mentioned above for their vehicles and systems. The cost of any given single launch is rolled into one number, but it must cover a multitude of expenses. Amortized over many decades, they may eventually pay for it all, but only if they can get enough business to fly their vehicles regularly and often. With NASA as their principal customer, will enough flights be purchased to take these New Space companies to the level they need in order to make a profit and survive?

Finally, Thompson asked, what is exploration if not living and working in space and contributing to the economy? He understands that exploration is more than going somewhere and planting a flag or collecting some rocks. Each time NASA launches a Shuttle, it puts 100 tons in space. By replacing the orbiter body with a cargo faring, we are creating a heavy lift launch vehicle. This Shuttle side-mount launch vehicle is something that fits the requirements placed on NASA for a new heavy lift vehicle. Its reliability has been consistently improved over the course of more than 30 years of flight experience and is more than adequate for many different kinds of missions throughout cislunar space. This is where the focus of our space program ought to be – and a zone of space specifically mentioned in the new agency authorization.

Preserving, adapting and using what we already have is smarter than destroying capability and starting again from scratch. We are putting faith in the emergence of space systems that will do what we want, when and where we want. We are told that to nurture and foster other providers of space access, we must throw away the bird in our hand and plant a revolutionary new bush, hopeful that it will grow and attract a variety of new birds. I leave it to you to decide the wisdom of such a restrictive course. Plant the bush but don’t throw away the only bird we now hold. We must be fully conscious about the realities of non-existent systems and preserve the space transportation capability on which America can rely.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)