AUSVI tested over 500 drones at their Las Vegas conference.

The newest eyes in the sky are drawing the attention of power companies, conservation groups, and the ACLU.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Drones-Florida-631.jpg)

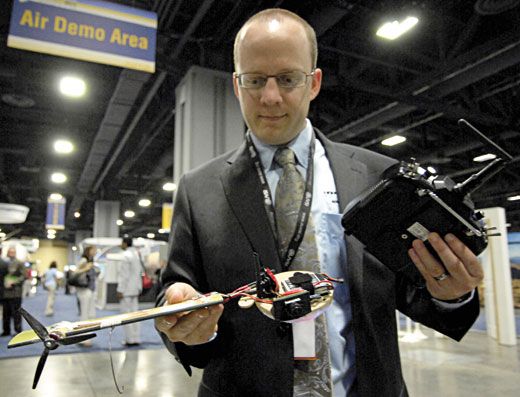

On platforms and tables in a Las Vegas conference room, little machines crawled and jumped, floated and sank, and zoomed across the air-conditioned airspace. The variety of robots and potential robot buyers at the annual gathering of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International last August indicates the changes that have taken place in the industry. Back in 1973, at AUVSI’s first meeting, there were only a handful of exhibitors and the only drone customer was the U.S. military, looking for small, agile, pilot-free aircraft it could risk sending across enemy lines.

This year, AUVSI made space for 572 exhibitors, most with a cadre of drone models—some hover quietly over a target, others disassemble on command, at least one looks like a flying garbage disposal—and they’re starting to move off the battlefield. In preparation for potential Pentagon budget cutbacks, the unmanned aerial vehicle industry is eager to shift to civilian markets, and, after years of silence on the subject, Congress last February ordered the Federal Aviation Administration to open the skies to drones by September 2015. Although there are many hurdles to cross between now and then, I came away from the AUVSI conference with this much: Pilots, you’ve got steely-eyed competition.

The FAA has focused its initial UAV rollout on small craft, under 25 pounds, which include almost 150 models made in the United States. To streamline the Certificate of Authorization process—a goal mandated by Congress—the agency is fast-tracking these little drones into parts of the domestic airspace, as long as they’re flown under 400 feet and by public safety agencies. (Many other potential users, like land-use managers and scientists, are trying, with some success, to get certificates as well. The FAA is making decisions on a case-by-case basis.) While public safety agencies are putting drones to work on various operations, a handful of sites will soon open to test general airspace integration. This December the FAA plans to designate six, in addition to an existing site, run by New Mexico State University, which since 2011 has tested drones in 15,000 square miles of lightly trafficked airspace around Las Cruces. At the test sites, operators will work out systems and protocols so they can advise the FAA as it creates nationwide regulations.

Unpiloted vehicles—some light enough to be hand-launched and often small enough to fit into a backpack—are already being used for everything from forest fire spotting to animal migration studies. The military-surplus, 4.2-pound AeroVironment RQ-11A Raven is one of two types of drones now flying for the U.S. Geological Survey. The USGS’s National Unmanned Aircraft Systems Project Office flies its Ravens for land management agencies in the Department of the Interior. Each project requires a special waiver from the FAA, which can take from a few months up to a year to obtain. In one test project, a Raven has been examining drainage infrastructure at a West Virginia surface mine. The drone team requires a pilot plus two observers to watch for aerial traffic. After a half-hour to assemble the vehicle, set up the ground terminal (a rugged laptop), a generator, and a communications antenna, launching the fixed-wing Raven is as simple as turning on the motor and hurling it into the air like a javelin. The drone, which has stabilized and gimbaled optical and infrared cameras in its nose, can fly for as long as 90 minutes, beaming live video to a monitor. When the team members see something on the ground that needs more attention, they instruct the Raven to circle the target while the pilot adjusts the camera to keep it in view. The Office of Surface Mining then uses the images to pick out trouble spots, such as a landslide that has blocked the flow of contaminated water to a treatment pond, and an inspector will follow up on foot.

When the Raven’s flight is over, landing is as low-tech as it gets: The vehicle comes to a stall about 20 feet overhead, then plummets nose-first, breaking into designated pieces that are easily reassembled. Reclamation specialist Natalie Carter explains that piloted helicopters once did the overflights, but they have become far too expensive; the office hopes that drones will now help inspectors cover the rugged ground.

“We expect that by 2020, unmanned aircraft will be the primary platform [for data collection] for the Department of the Interior,” says Mike Hutt, USGS’s unmanned aircraft project manager, who notes that drones not only perform surveys once flown by expensive piloted aircraft, but also have started to take on tasks no one has undertaken before. “We have a mandate to record what’s at an archaeological site, which includes ancient artwork,” like cliffside carvings, he says. “A lot of these have never been photographed.”

Drones would be particularly useful in Big Bend National Park in southwest Texas. The 800,000-acre park is one of the most geologically rich sites in the United States, featuring a once-active volcano system and ongoing, large-scale erosion from the melting Rocky Mountain snow that forms the Rio Grande, and it is exceptionally difficult terrain to study on foot.

The USGS has taken on dozens of these kinds of unmanned trials: checking fence lines in Hawaii that keep feral hogs from protected vegetation, counting migratory sandhill cranes, and monitoring the temperatures of mountain streams threatened by climate change.

For surveys of vast areas, fixed-wing drones are suitable, but when the task requires carrying a payload or hovering over a spot, agencies are turning to rotary UAVs. Most have multiple motors, each sitting at the end of arms radiating from a central hub that houses navigational instruments, microprocessors, and a rechargeable battery. Depending on its diameter and number of rotors, a multi-rotor like DraganFlyer X8, microdrone 1000, or Ascending Technologies’ Falcon 8 can lift payloads weighing nearly two pounds.

Typical multi-rotor flights last less than 10 minutes, but some models can stay aloft for more than an hour. In Britain, music video producers and real estate firms have used them to provide potential buyers with aerial videos of properties (not yet legal in the United States). Authorities in Germany used microdrones to carry sampling equipment to test hazardous smoke during a chemical plant fire.

Multi-rotors still have a way to go: They’re inefficient in cruise, short on payload, and unable to autorotate to a safe landing if a motor fails. But for simplicity, durability, and ease of modification, they are hard to beat. Michael Achtelik of Ascending Technologies points out that, aside from the mounted camera, the quadcopter has only 12 moving parts: four motors and two bearings per motor.

In Colorado, at the Mesa County Sheriff’s Office, Unmanned Aircraft Program Manager Ben Miller uses one of DraganFlyer’s smaller versions, the X6, for capturing quick information above crime scenes, accidents, and fires. (The office also has on hand a Falcon fixed-wing drone, suitable for covering more territory during searches for lost hikers in rugged country.) The X6 weighs two pounds, flies at up to 30 mph, and, at about $22,000, costs a fraction of what a new squad car costs. An hour in a manned helicopter can cost 50 to 300 times more than one in the little multi-rotor. One September morning, Miller heard that the Grand Junction Fire Department was fighting a fire at an events center, so he hurried to the location with his X6 and told the incident commander that he’d “brought a helicopter.” The chief looked around for the aircraft, then looked stunned when Miller pulled it from the back of his SUV. The little drone found an active part of the fire that firefighters had missed, and its stack of aerial photographs helped the arson squad later pinpoint the fire’s origin.

Hutt says the USGS experience with drones is similar: They show their greatest worth not in spotting a fire at its outset, when the smoke is easy to see, but in the final, grueling task of stamping out every last ember. In rough country, buried hotspots can be hard to pinpoint, especially when fallen trees or rocks have thrown an insulating cover over them. “One fire in Colorado that they thought was out, wasn’t,” says Hutt. “On a huge fire, mop-up is very labor-intensive. If they had a small unmanned aircraft, handcrews could operate it.”

While rotary drones were being tested over U.S. forests, on the other side of the world a hybrid drone was undergoing one of its first civilian trials. After four nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi complex in Japan were catastrophically damaged during the March 2011 earthquake, Tokyo Electric Power Company engineers called for help from above. They needed information about the upper reaches of each reactor building, but because the exposed fuel rods were giving off hazardous gamma radiation, sending in piloted aircraft was out of the question. The task required something that could hover and take images amid gusty coastal winds, and fly around and into the wreckage. It was a job for Honeywell’s RQ-16 T-Hawks, drones about the size of pony beer kegs. The T-Hawk is known as Dusty Bin by military units that have been using it for patrols in Afghanistan and Iraq. (The battlefield drone was named for the tarantula hawk, a vicious wasp that preys on spiders, though the shortened name sounds much more civil.)

The sturdy T-Hawk—a single rotor tucked inside a shroud, plus two stubby protrusions for navigational gear and sensors—can knock into things without flying to pieces. Over three months and 40 missions, the T-Hawks’ sensors, including radiation dosimeters attached with zip-ties, scrutinized the damage at Fukushima. Reactor engineers watched the live video and made on-the-spot suggestions to the drones’ pilots about where to go next. “It was more like operating a [ground robot], with one person to drive and one to look,” recalls Robin Murphy, director of the Center for Robot-Assisted Search and Rescue at Texas A&M University, who helped coordinate the effort from a crisis headquarters in Tokyo. Using the T-Hawks, the engineers and operators were able to perform assessments out of range of the high-radiation zones.

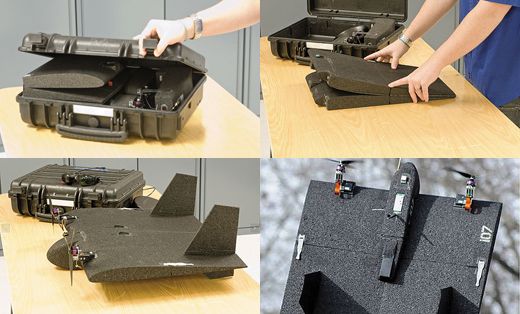

An important feature of these small drones is their portability; because their range is relatively short, operators need to pack up and move to reach greater distances. Terrence McKenna at the Aurora Flight Sciences booth at the Las Vegas show demonstrated to visitors how the new Skate vertical-takeoff model shifts from flight mode—when it looks like a flying shingle—to backpack mode. To break the Skate down, McKenna removed the two motor pods (attached with magnets), slipped off the vertical stabilizers, pulled loose the battery and nose-mounted electronics pod, and pulled out stiffener rods at the ends of the wing. Then he folded up the wing, made of hinged panels. The whole two-pound machine fits into a sling-pouch of the size used to tote a camping chair. The price for Skate, including ground control equipment, starts at around $35,000.

Before DraganFlyers, T-Hawks, Skates, and their compadres can fly in the United States—beyond a handful of trials and operations requiring waivers—regulations have to be established and the drones themselves have to be improved. The biggest challenge is getting drones to play nice with everything else that’s in the air.

Requirements for collision avoidance gear and rules for flights near airports and beyond the pilot’s line of sight must be established. Today, with few exceptions, drones have to stay five miles from airports. Keeping no-fly zones that large would be a big problem for routine drone use over a city like Seattle, which is spotted with airports, heliports, and seaplane bases. Honolulu officials learned this rule the hard way after the city bought a $75,000 drone to assist with port security, only to be notified by the FAA that this would put it too close to the international airport on Oahu. The aircraft currently sits in storage.

AUVSI attendees in Las Vegas were quite eager, then, to hear University of Alaska’s Greg Walker, director of the Unmanned Aircraft Program, tell them that during a January 2012 fuel shortage in Nome, the FAA granted an airport-proximity exemption for a drone. To prepare for the much-needed arrival of a Russian fuel-oil tanker, state authorities requested permission to fly a Datron Scout multi-copter to photograph sea ice—including at locations within a mile of the city’s busy airport. Just three days after the state’s request, the FAA signed off on it. Alaskan operators offered to set up their prototype ground-based sense-and-avoid system, since the Scout has no sensors aboard it to enable the craft to steer clear of collisions on its own, but the FAA required only automatic radio recordings that notified pilots in the area to keep an eye out for the unpiloted vehicle and increased staff to watch the airspace.

The agency won’t let that deficiency slide forever, though. “If unmanned aircraft had ‘sense and avoid,’ ” says Patrick Currier of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida, “the FAA would be that much more willing to open up the airspace.” Drones sold today don’t yet have such smarts. Currier explains that with existing technology, the most autonomy drones get is, after a remote-controlled takeoff, being let loose to fly from one GPS point to another, adapting for crosswinds.

What the industry really needs is a system that integrates smoothly with bigger airspace changes already happening under NextGen, the FAA’s overhaul of the nation’s air traffic control system. By shifting tracking from radar and ground controllers to GPS signals and electronics aboard the aircraft, NextGen will allow more flexible and accurate flight plans. Civilian drones rely heavily on GPS for navigation, so it seems as if the two systems should work seamlessly. But drone experts would still like to develop independent systems—giving them the redundancy that UAVs lack because they don’t have a thinking, reacting pilot on board. Researchers in one European study and at the University of Pennsylvania, among others, are working on methods to guide small unpiloted aircraft (or more likely, a swarm of them) that have no dependable access to GPS signals and instead have to rely on a mix of “signals of opportunity”: camera-based navigation, landmarks, and whatever radio signals are available. The problem of a GPS-denied environment is a hot topic among military thinkers and disaster planners, and was brought up many times at the AUVSI conference. It’s already relevant for anyone, or anything, having to navigate a GPS-blocking maze of tunnels, urban canyons, or the hallways inside steel buildings.

Some university researchers are pushing for sensors and onboard computers powerful enough to convert video into three-dimensional maps in real time, allowing the vehicle to take over some piloting duties when conventional means of navigation and control break down. The GRASP lab at the University of Pennsylvania teamed with Tohoku University in Japan to map an earthquake-damaged building in Sendai, using the Japanese team’s ground robot, Quince, and the GRASP lab’s quadcopter, a highly computerized research model from Ascending Technologies. Quince carried the quadcopter into the damaged building and up the stairs. On command, the robot’s securing arms swung away and the quadcopter lifted off its tiny helipad. Its job was to extend the reach of Quince by flying up and down the damaged corridors, mapping as it went with the help of a laser rangefinder, and avoiding obstructions like dangling wires. When the job was completed—the vehicle worked well enough to map three floors—it found its way back to Quince and landed.

For now, some of the limits on drone use will stay in place, such as flying no higher than 400 feet above ground, flying during daylight using visual flight rules, and staying within the pilot’s line of sight. Even under these rules, the public-agency experience should help pave the way for routine use by commercial drone operators: adding rich photographic detail to existing maps; inspecting roofs, towers, and bridges for needed repairs; gathering news; or serving as temporary relays. South American energy companies already use drones to inspect hard-to-reach equipment such as flare booms on offshore oil rigs.

The power industry hopes that drones can speed up preparations for transmission-line repair after big storms, explains Drew McGuire, an engineer in Southern Company’s research arm. “Repair work depends on accurate assessment,” he says, “and poor assessment means wasted money and longer outages.” The industry wants a camera-wielding aircraft that can arrive on the scene faster than helicopters (which might be grounded by storms), inspect more power-line miles per dollar, and get imagery back faster. Lightweight drones—relatively inexpensive to risk in poor weather—might meet such needs.

Though there is enormous potential for drone use in emergency situations, infrastructure inspection, and ecological monitoring, many buyers still aren’t sure exactly what they need. “The industry is pretty immature,” says Embry-Riddle’s Currier of the current offerings at AUVSI. He compares it to the early years of auto manufacturing, when motorists had hundreds of brands, and no company dominated. “It’s hard to tell which is a production-ready aircraft by just looking at it,” says Roy Minson, a vice president at AeroVironment Inc., a leading producer of unmanned aircraft, including the Raven and another fixed-wing, the Puma AE, both of which are popular with the military. But the company is spending millions to refine a multi-rotor it calls the Qube, aimed at civilian firefighters and officers who need an easy way to get a camera overhead and transmitting video within minutes.

“There’s an enormous need for fast response, to get aerial imagery in minutes,” says John Appleby of the Homeland Security Advanced Research Projects Agency. But a drone is no bargain for those who bought the wrong kind, or who can’t find enough uses for it (just ask the Honolulu port authority). In 2010, officials in Polk County, Florida, decided after a year of drone trials that the cost of meeting FAA regulations—in particular, the cost of pilot training—was too high, and halted use of its fixed-wing model. First-time drone buyers don’t always consider the limitations they’ll be under, not just the FAA oversight but also weather, battery life, image quality, piloting skills, and the public’s privacy concerns. Still, a temptation to run out and buy what Ben Miller calls the latest “shiny black thing” could grow as public agencies face less federal paperwork on the way to drone deployment. “Our advice to public safety agencies is to figure out your environment, know what data you need to collect, and then sit down and do the shopping,” says Doug Davis, who once directed the FAA’s work on unmanned aircraft and now directs the Global UAS Strategic Initiative at New Mexico State University.

When the buyers are ready, there will be plenty to choose from. The drone-making industry is furiously at work trying to make sure the vehicles will be useful once in the skies. Sensor quality is the fastest developing front in unmanned aircraft, according to Currier. Tests over the last two years by the Los Angeles County Fire Department suggest that when it comes to spotting lost hikers (simulated by actors) in rough country, machines that can deliver steadier, higher-resolution video are needed. The Department of Homeland Security began trials this fall at Fort Sill in Oklahoma to study how drones might be used to scan for hazardous chemicals and radioactive materials.

With nobody on UAVs to complain about a bumpy ride, and many niches for the vehicles to occupy, inventors are eager to develop capabilities and solve problems, like the short duration of multi-copter flights. One solution could come from LaserMotive, which recharged a quadcopter by aiming a high-powered laser at the aircraft’s photovoltaic panels. “If it’s powered from the ground, it never takes its eyes off the target,” explains Tom Nugent at the LaserMotive booth. Some new drone ideas feature flapping or rotating wings—or a single rotating wing. Lockheed’s Samurai prototype is an oversized, motorized maple seed. Sitting on the ground, this foot-long, lopsided gizmo might look like something that broke off a conventional drone, but in flight it’s a marvel. Out-simplifying even the multi-copters, it flies with just two moving parts: an electric motor and a single aileron for its wing.

While engineers fix the practical problems, drones still face one more major issue. “We understand as an industry that we’ve got a public relations problem,” says Paul McDuffee, vice president of government relations and strategy at Insitu and an AUVSI board member. He is referring to the worry that routine use of drones for surveillance in our own skies will conflict with citizens’ expectations of privacy. Some anti-drone activists want bureaucrats to throw up obstacles like “no-drone” zones and bans on purchases. The American Civil Liberties Union issued a report last year with recommendations on privacy protections, such as image retention restrictions and publicly available usage procedures, none of which were included in the bill passed by Congress. Still, many Americans accept drones’ use in law enforcement. A survey conducted in August by the Associated Press and the National Constitution Center found that 44 percent of respondents supported the idea of law enforcement using drones to assist in police work; 36 percent were opposed.

In June, AUVSI released a voluntary code of conduct for drone operators that McDuffee hopes will allay these concerns, particularly because even if privacy advocates don’t like it, drone use will expand—though, he hopes, to the public’s benefit. Responding to an anti-drone column in the Washington Post, AUVSI president Michael Toscano wrote: “With growing international demand for this technology in countries such as Japan, Australia, and Chile, where it is used in everything from agricultural to anti-poaching efforts, there is incredible job-creation potential.” Put enough bureaucracy in the way, he added, and the United States will lose out to other countries.

A few nations have jumped ahead in legalizing the routine use of small drones by commercial operators. For unmanned aircraft weighing less than 330 pounds, the European community allows its members to pursue their own rules, and several, including the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, and the Czech Republic, have already stepped ahead of the United States by passing rules that permit commercial use of smaller drones.

British company HexCam, for example, began flying its small camera-equipped multi-copters-for-hire earlier last May. It received certification of the drone gear and its safety practices under the United Kingdom’s Light Unmanned Aircraft System Scheme, a set of airworthiness regulations for drones weighing less than 44 pounds. The clearance allowed the company to get a license from the Civil Aviation Authority and acquire insurance. “It is great that we are able to operate commercially in the U.K., and I hope that the FAA opens U.S. airspace,” says Elliott Corke of HexCam. Approximately 100 commercial operators are licensed to fly small drones around Britain.

Despite trepidation at FAA delays, technology that can only move forward so fast, and a privacy rights argument that is unlikely to be resolved soon, the new world of drones is coming. Like so many things invented for war, unpiloted vehicles can be given a practical purpose in civilian life. One day, not long into the future, you might be lost in the woods and relieved to be the target of a little drone buzzing overhead.

James R. Chiles has been writing about history and science for 33 years. Random House published his social history of helicopters, The God Machine, in 2007.