Dutch Safety Board: Ukraine Should Have Closed its Airspace Before MH-17 Was Shot Down

The investigators’ preliminary report details the airliner’s last moments.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/54/0654df51-9661-45c4-8ef7-43e92757c711/mh17_missile.png)

The missile that brought down Malaysia Flight 17 on July 17, 2014, detonated just feet from the left side and above the cockpit of the Boeing 777, the Dutch Safety Board announced today. The 9N314M missile warhead was loaded with small bowtie and cube-shaped metal objects that “ejected with tremendous force,” according to Tjibbe Joustra, chairman of the government board that presented its findings to journalists at the Gilze-Rijen air force base in southern Holland.

Hundreds of these projectiles were embedded in the bodies of two pilots and the purser who was on the flight deck at the time. They were killed immediately. Missile fragments were also found in the cockpit. Damage to the front of the airliner caused it to separate, after which the rest of the airliner came apart.

There was no evidence that the passengers were injured directly by the missile, but the impact of the cabin falling from an altitude of 33,000 feet and hitting the ground while inverted was not survivable, the investigators found. The board’s report pointed out that the rapid decompression of the cabin, along with turmoil from wind and debris flying around, would have probably led to unconsciousness or reduced awareness among the passengers in the minute to 90 seconds it took for this section of airplane to fall from the sky. All 298 people onboard died in the attack, 193 of whom were Dutch.

Anyone expecting the Dutch Safety Board to identify who was responsible for firing the missile would have been disappointed; Joustra said the subject was “outside the mandate of the safety board.”

It is commonly believed that a BUK surface-to-air missile system provided to Russian-backed separatists in Eastern Ukraine was used by them to fire on the airliner because the fighters believed the plane to be a Ukrainian military airplane.

Even without an answer to the troubling question of who did it, the safety board’s news conference was a dramatic affair complete with videos, animations and a theatrically illuminated, partial reconstruction of the airplane.

And Joustra did have an accusation to make.

Standing on an elevated platform only slightly farther away from the cockpit than where the authorities believe the missile detonated, Joustra said that no nation or aviation organization paid enough attention to the risks associated with flying airliners over combat zones.

In the days prior to the downing of MH-17, two Ukrainian military planes were hit while flying at altitudes used by airliners. That should have prompted the country to close the airspace, the Dutch investigators concluded, but it did not.

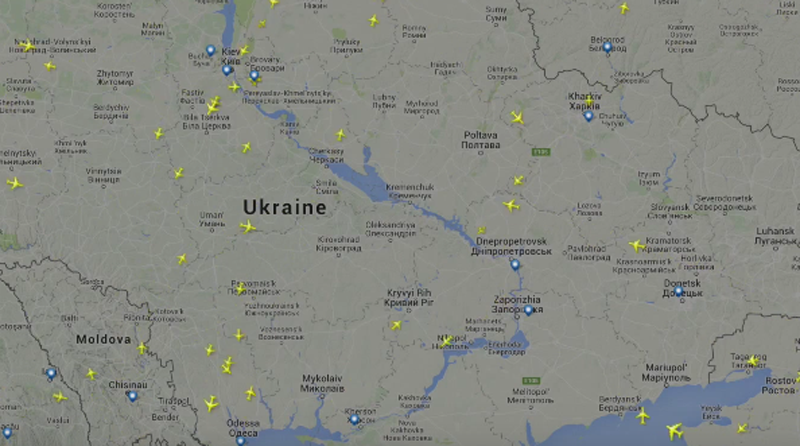

“Thirty-two different countries flew over an area where armed conflict was taking place. MH-17 was one of 160 flights that operated there,” Joustra said. In the opinion of the air safety investigators there was sufficient reason to close the airspace but Ukraine authorities failed to do so. States collect fees from airlines for the use of their airspace. Whether this contributed to Ukraine’s decision was not addressed.

Flight 17 points up the flaws of relying on states in political turmoil to recognize just how risky their airspace is, the report said. The board recommends that airlines, governments and the International Civil Aviation Organization perform their own assessments.

In its lengthy report, the safety board writes that instances are rare of airliners being hit by missiles over conflict zones, but the consequences are catastrophic, so statistical improbability isn’t an adequate measure of whether the practice is safe.

The board did not absolve Malaysia Airlines or organizations like the International Air Transport Association from responsibility for the decision to fly over Ukraine. “Operators cannot take it for granted that open airspace above a conflict zone is safe,” the report said.

One of the board’s recommendations is that governments require airlines to justify routes over conflict zones regularly, or at least once a year.

Earlier this year, the International Civil Aviation Organization launched an information-sharing website where nations can contribute intelligence about threats to civil airspace. In October, 12 hotspots had been identified from Afghanistan to Yemen, including Ukraine.