Taking Flight

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/40/2e400a79-0f43-445c-8892-ba9650aec610/01-1a_as2021_weallflyintroduction-fromawindowone_live.jpg)

How do we love flying? Our readers count the ways. Balloons, gliders, biplanes, jets—the methods are many. But no matter the type of flying machine or the mission that called it to the sky, all have one thing in common. Every flight has a story.

Let’s Just Take the Train

I have a commercial license with multi-engine and instrument ratings, but the story I want to tell is about an experience that my dad had in 1918. He is no longer here to tell about it, so I’m going to do it for him.

My dad, Lieutenant Clarence R. Walker, was a flight instructor in the U.S. Army in 1918 when he was ordered to survey the route from Taylor Field in Montgomery, Alabama to Arcadia, Florida in preparation for moving his unit to the new location. (The U.S. Army Air Service had established a primary flight school at Taylor Field with nearly 200 Curtiss and de Havilland trainers.)

He and another lieutenant left Taylor Field in a Curtiss JN-4D Jenny on the morning of August 12 with fuel stops at Souther Field in Americus, Georgia; Pine Park, also in Georgia; and on to Perry, Florida—roughly the halfway mark of the journey—where he was forced to land in a field because of a rain storm. After the storm subsided, he was unable to get off the sandy field, but townspeople helped him push the airplane to the road. On his first takeoff attempt, he had engine trouble and smashed a wing on landing. Because Perry was a sawmill town with plenty of woodworkers, he found a few folks who could repair his wing, and he set out on his second takeoff attempt. This time he struck a tree with the wing and wrecked the machine. The airplane was returned to Taylor Field by rail. His logbook makes no mention of injuries to himself or to his passenger, so I assume they returned on the train also. —James Walker, Westmorland, CA

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/01/560127e4-77f5-4917-be54-bb4da97fe0a5/01-4r_as2021_varietyreadersstories_100bwalkerjenny_3108_live.jpg)

“The ground under you is at first a perfect blur, but as you rise the objects become clearer. At a height of one hundred feet you feel hardly any motion at all, except for the wind which strikes your face. If you did not take the precaution to fasten your hat before starting, you have probably lost it by this time.”

—From “The Wright Brothers’ Aeroplane” by Orville and Wilbur Wright, The Century Magazine,

September 1908. This was their first published description of their flights.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/95/de952bac-aade-45e5-b21f-e17166a24beb/wright-brothers.jpg)

The Night, the Ocean, and the DC-3

We staggered off the reef runway at Honolulu and ascended over the utter black of the Pacific at night—two overloaded DC-3s. We grunted and groaned our way up to 6,000 feet, and tacked south and west for Tarawa, some 2,100 miles from Hawaii. Our ultimate destination, Bangkok, lay far over the horizon in both conception and reality. Our job was to deliver these venerable Douglases for a film being made in 1991 Vietnam. With extra fuel bladders, tanks, and a barrel of oil battened down in the back, a rudimentary GPS, and a sometimes contrary radio navigation system to guide us, we took on the night and the big blue sea. We were without radar, and soon, because of solar storms, without communications—the high-frequency band was reduced to a hash of impenetrable static.

We kept a casual station with each other, the sight of the other’s flashing red beacons providing comfort, as we quietly noted crossing our point of no return, trusting in God and Pratt & Whitney, as our bards Gann and St. Ex had in eras past. Dawn crept up on us, and soon we were in the Intertropical Convergence Zone, where storms boiled up into the flight levels beyond our ability to climb. We gamely dodged, getting shoved and bumped by the turbulence, till finally we were clear, in full daylight, with HF communications miraculously restored just in time to spy our destination emerge from the sea: Tarawa, a string of pink coral islets, a beautiful sight for our land-hungry eyes. We descended like two weary seabirds and gently alighted, after 15.5 hours aloft. I will always love the DC-3. —Tony Buttacavoli, Commerce Township, MI

Narrow Escape in a Privateer

We were 30 feet above the water, 220 knots in a PB4Y-2 with a 12,000-ton Japanese tanker broadside in front of us. Our intention was to kill it like “shooting fish in a barrel.” The problem was it could shoot back; we had to get in and out fast.

It was 1944 in Tsushima Strait, between Korea and Japan. Kenny, the pilot, and me, the co-pilot, were part of a crew of 13 in a four-engine airplane with a 500-pound general purpose bomb fused for a four-second delay. The plan was to drop the bomb about 500 feet short of the ship so that it would either skip into its side or explode under it. We would immediately climb over the superstructure and masts and, unscathed, leave the scene. This all went well except the “unscathed” part.

At about 200 feet, we heard loud reports and the PB4Y yawed hard to the left, with heavy vibration, and started down. Kenny strained at the yoke to recover, but was losing. I grabbed the yoke and together we got the ship righted, but we were still losing altitude, so straining on the yoke with my right hand, I adjusted the trim tabs with my left and increased the two port engines to takeoff power. By now, we were down to five feet above the water. I called out over the intercom, “Prepare for ditching.” This meant jettison all ordnance and non-essential equipment. This the crew did energetically.

With the lightened load, better trim, and increased power we began a climb back to 1,000 feet. We still had 800 miles to go to get back to base. Navy ships and radars based on Okinawa guided us home. But Kenny had no aileron control and could only turn to the left, and then only by skidding with rudder. It was a rough trip. Later, we learned we took three 40mm rounds in the port wing and flak in the tail.

I am now 101 years old and still recall the day! —William W. Howison, Parrish, FL

A helicopter is like a magic carpet. You can’t believe the places it takes you. Once we flew News Chopper 3 from Phoenix up to Seattle. We flew the coastline the whole way at 200 feet. We saw whales, dolphins. We flew over Alcatraz. But the highlight of my flying career was flying under the Golden Gate Bridge. I know what you’re thinking. And yes, it is legal.

—Bruce Haffner, Chopperguy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/07/6f0758f2-8207-4e0c-88cd-2cb0e942adb9/01-4ze_as2021_varietyreadersstories_brucehaffnerggbridge_live.jpg)

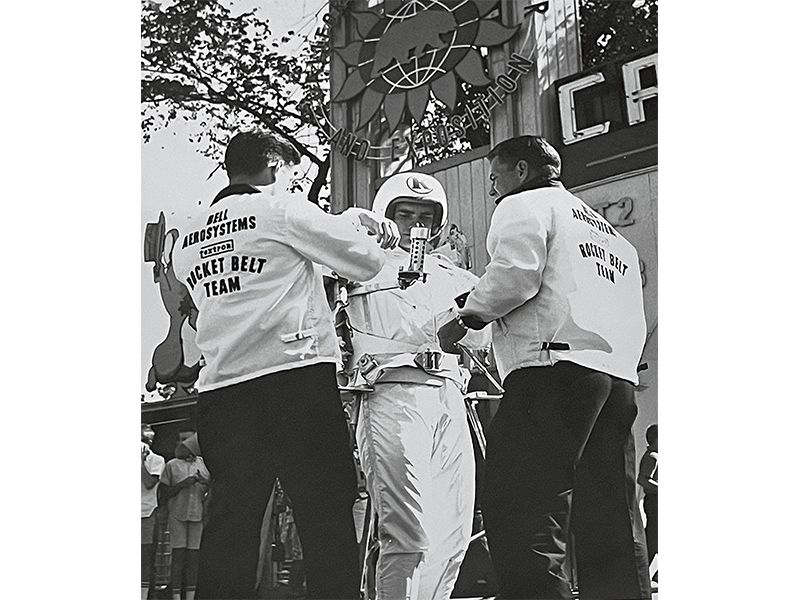

The Rocket Belt Takes Center Stage

Up to this point the demo flying I had done was on the grass strip at the Bell plant. Now here I was at the 1964 California State Fair in front of thousands of people. Our part in the Grandstand Show was to take off halfway down the racetrack, fly up in front of the grandstand, turn, and land on the stage set up across the track from the stands—about a 100-yard flight. As evening approached, I could feel my pre-game jitters. Time to fuel the Belt and get into my flightsuit. I’m to fly in the dark—all lights will be out except one spotlight that will be following me.

The announcer begins, “Ladies and gentlemen, you are about to witness a scientific demonstration of the Rocket Belt, designed and developed by Textron’s Bell Aerosystems Company of Buffalo, New York.” (Over the next six years, I’ll hear that introduction hundreds of times.) Suddenly, I feel the weight of the 125-pound load that’s strapped to my back. The announcer finishes the introduction, and almost without thinking I hit the throttle and down the track I roar. The guy on the spotlight can’t keep up, but there’s enough light coming in from the fairgrounds to light my way.

Off to my right, a distraction—pop, pop, pop—a hundred flash bulbs are going off, and I’m there already, at the stage, and I begin to descend. Next to the stage is the orchestra pit with 35 musicians.

The spotlight is shining on the spot where I’m to land on the stage. I decide rather than a sharp turn, I’ll make a sweeping turn over the orchestra pit and land facing the crowd. As I enact the plan, I get my first low-fuel warning alarm—10 seconds left. As I pass over the orchestra, I have no idea—and neither do the musicians in the pit—what is about to happen. No one had warned the musicians about the blast, the heat, and the noise. The rocket blast begins to blow sheet music all over the place. The musicians jump up and scurry to get out of harm’s way. Instruments fly everywhere.

I do a lateral side-slide to get out of the paper storm and over the stage—six seconds left; I must set this thing down—but the stage is covered with what seemed like miles of wires for all the microphones and stage lights, whipping dangerously in the rocket’s blast. I try backing up, and the blast blows the stage clear. And I land. I wave to the crowd. —William Suitor, Youngstown, NY

Solitude Above 70,000 Feet

The U-2 demands a uniquely physical engagement from its pilot at low altitude, but at its classified operational altitude, the experience is, in a word, serene. The steady resonance of the single engine is one of a few sensory inputs, accompanied by the flow of cooling air feeding into the pressure suit and pressure-fed oxygen pumping into the helmet. The sense of motion is almost imperceptible, and the pilot is left to marvel in near silence at views bested only by true orbital flight.

On a U-2 pilot’s patch are the words Solum Volamus, or “We Fly Alone.” Flying a U-2 to base after a long mission can be trying for a pilot exhausted by hours aloft, followed by increasingly heavy control forces as the air thickens in the descent. But the real challenge is the isolation faced at the most distant point on a mission—a single ship with a single pilot, and often deliberately in radio silence. That point captures the spirit of a mission that relies principally on the airmanship and experience of aviators who face the threat of malfunction or provocation by an adversary with little beyond their own resources to determine the outcome. —Andrew McVicker, Califon, NJ

First Flight: A Love Story

The Noorduyn Norseman floatplane docked on a lake in northern Ontario was loaded with camping and fishing gear and four other passengers besides me. At 12, I was ready for the adventure of fishing on an isolated lake for 10 days. But I wasn’t prepared for experiencing my first flight. I was assigned the co-pilot’s seat. I gazed in wonder at the wall of instruments and watched in total awe as the pilot started flipping switches, pushing and pulling as the engine caught and came to life.

As we taxied away from the dock it seemed as though we were sitting high in a bulky, overloaded boat. But then, as our speed increased, a battle emerged between the water saying “You’re a boat” and the air insisting that the airplane rise. Nothing could have prepared me for the feeling of breaking free of the lake. The fishing and camping were great, but I fell hard in love with flying.

Twelve years later I would find myself out over the Gulf of Mexico, calling ball on final approach during my carrier qualification on the USS Lexington in a T-2 Buckeye jet. —Ross (Tony) Costanzo, Monroe, CT

The Salvo Bombing Contest

By August 28, 1969, my best friend and I had convinced his dad to allow two 17-year-olds with less than 200 hours between us to fly his 1939 Porterfield to the Antique Airplane Association’s annual fly-in at Ottumwa, Iowa. A dawn launch from Tulsa’s Harvey Young airport followed by a quick right turn put us over the east-bound lane of I-44. Our onboard collection of TEXACO road maps verified we could pick up railroad tracks at Joplin that would lead us to Ottumwa.

Saturday’s Salvo Bombing Contest announcement piqued our interest. Neither one of us knew what Salvo Bombing was, but we boldly signed up and received a bag of three tablets of Salvo laundry detergent. To us, taking off with an antique washing machine farther down the runway seemed reasonable, and joining the pattern to drop a Salvo tablet into the washing machine seemed a fair test of skill. Lining up for our third and final pass with our last tablet, undaunted by several near-death experiences, we pressed on in our bomb run. Leaving line-up to the pilot flying, I yelled commands of “Lower, lower, lower, lo….” Suddenly we impacted the runway and bounced over the tub. The impact made me drop the tablet.

The flight home, with a small trophy proclaiming SALVO CONTEST CHAMPION tucked in a sleeping bag, abruptly ended in a field outside of Neosho, Missouri. The engine had failed. Now driving back to Tulsa, I knew it would be easy to write the obligatory essay, “What I Did Last Summer.” —Carl Gull, Oklahoma City, OK

Somewhere in Nevada

Taking off in a hang glider from California’s White Mountains has to be on the bucket list of aviation: the 100-mile vistas, thermal rocket rides of 2,500 feet per minute, the bliss of silent soaring. One summer, I got the ride of my life. At about 1,200 feet, the variometer, which emits a series of cheerful chirps indicating lift, screamed like a dentist drill. My vertical ascent, I am certain, far exceeded forward flight. I was like a leaf in a windstorm. At 17,999 feet—hang glider pilots use this term tongue-in-cheek because anything above that is controlled airspace—I thought What the heck, never been here, do it now, and headed north out into the desert, into “dinosaur land,” to see how far I could go. There was rime frost on my clothing and down tubes. On the valley floor, I could see tiny vehicles and trucks moving slowly through cloud shadows on U.S. 395.

The adage “what goes up, must come down” is certainly true of air masses. I was only five minutes past Boundary Peak and into Nevada when the variometer again sounded. I was going down very fast—in the parlance, “getting drilled.”

At 4,000 feet I realized I needed a place to safely land. It was a considerable distance from 395, and I tried unsuccessfully to raise my driver on the radio. (This was long before GPS.)

And then, in the wash next to the road where I chose to land, I saw a glider on the ground. The cross-country god is with me today, I thought. Nothing better landing out than to have company. After touching down and unhooking, I looked over to see a woman peeking around her wing in astonishment. “Why did you land here?” she said in a French-Swiss accent. “Same reason you did,” I said. “Do you have a ride?” She was a professional pilot, practicing, and we had a long, interesting conversation in the dark, this woman from another continent and I, sitting by 395, waiting for one of our drivers to retrieve us after a sensational day, landing out in a dry creek somewhere in Nevada. —John Merrill, Somis, CA

A Dragon in the Tree

Anyone who has heard the roar of a hot air balloon’s burner will appreciate this story.

It was a very early Saturday morning in September 1979 when I lifted off in my balloon from a field in Jeffersonville, Indiana, a community just across the Ohio river from Louisville, Kentucky. The winds aloft were forecast to be from the west, taking me east across Louisville and into an area known to have a number of potential landing spots. As I climbed to several thousand feet and continued toward the river, I noted a gradual southerly shift in my direction. The winds aloft were not proving to be what was forecast.

I sampled different altitudes up to 4,000 feet in trying to find steering winds that would take me east—to no avail. I was being carried directly towards Standiford Field (today Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport) in Louisville.

As I continued, I found myself traveling over a part of old Louisville, an area where a co-worker lived. The area has a very heavy growth of trees making it somewhat difficult to determine a balloon’s precise position with respect to objects on the ground, but I was able to spot enough landmarks to realize that I was about to almost overfly Steve’s home. I was just above the trees when I called his name—“Steve! Steve!”—at the top of my lungs. I didn’t see anyone on the ground, so I ventured on and finally found a place to land.

The following Monday I saw Steve in the office and mentioned that I flew over his home on Saturday morning. He said, “Oh that was you?” He explained that he was sleeping when his two young daughters burst into his bedroom yelling “Daddy! Daddy! There’s a dragon in the trees, and it’s calling your name.” —David Arnold, New Albany, IN

Is This Robby Gaines?

All mothers worry. Unfortunately, mine knows my tail numbers.

When I was a young pilot, I rented a Cessna 172 to fly from Emporia, Kansas to Arlington, Texas. I got to the airport and walked to my airplane wearing aviator sunglasses. I was cool. The Top Gun movie theme was playing in my head.

I experienced a two-hour delay. Because this happened before cellphones, there was no way to inform my parents.

As I entered the Dallas-Fort Worth flight control zone and contacted Arlington, a sense of pride came over me. I was flying with the big boys.

“Arlington approach, 714 Foxtrot Bravo, inbound to Arlington, request airport advisory.”

“714 Foxtrot Bravo, descend to 2,000, turn heading to 270.”

I was proudly flying through one of the busiest airports in the world.

“Arlington approach, 714 Foxtrot Bravo is descending to 2,000, turning to 270.”

“Roger, 714 Foxtrot Bravo. (Pause.) Is this Robby Gaines?”

What? How did they know that? Was I in trouble? A thousand questions were running through my mind as I pressed the transmit button and hesitantly replied, “Yes, this is Robby Gaines.”

“Your mother wants to know where you’ve been.”

My pride quickly melted away. I imagined I could hear the laughter of all the pilots flying around DFW. What could I say? My mom had been calling the tower and asking, “Where was 714 Foxtrot Bravo?” —Robby Gaines, Artesia, NM

From a C-130 with Care

At Air Station Kodiak in the 1970s, I maintained rescue and survival equipment and flew as a C-130 dropmaster. One winter day, the air station’s rescue coordination center received a distress call from Gambell, St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea, 650 miles northwest of Kodiak. A small boat of native walrus hunters was overdue. I was on the C-130 “ready” crew and assembled a container of survival gear to drop.

Our flight took about two hours. The surface of the sea was a mosaic of white polygons. Only about 50 miles from USSR airspace, our rescue mission required U.S. state department approval. We descended to about 1,500 feet and searched for the boat on a track vectored from Gambell. The weather was closing in, and we had only a few hours of daylight. The vector pointed precisely toward the hunters, and we spotted them quickly. We deployed smoke and dye markers onto the location. I prepared the drop and opened the ramp. As we made our approach, I was given the command, “Drop, drop, drop!” From a 150-foot altitude, I clearly saw the men cheering. The airdrop was right on the money. We orbited until a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter picked them up.

Our C-130 crew spent the night in Nome, the aircraft in need of minor maintenance. The locals feted us with food and drink. I demurred and went back to my room, exhausted after a busy day. My reward was the laughing men on the ice. —Robert F. “Bob” Moyer, San Antonio, TX

Once a Pilot…

One of my most memorable flights was special not because of the aircraft or the destination, but because of who flew the airplane—a 102-year-old former Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) pilot named Maryalice Ford. She had not been in the cockpit of an airplane in decades, but in the summer of 2019, the organization my husband and I serve with, Mission Aviation Fellowship, gave her the chance to take to the skies again. Our chief pilot, Brian, flew right seat in a Cessna 206, and after a short circuit over our town of Nampa, Idaho, he gave Maryalice the controls. I leaned forward in my seat and caught a glimpse of the wide grin on her face as her hands confidently took the yoke. I marveled that this tiny woman, propped up on several pillows, was commanding our aircraft. I wondered if, as she flew, she was remembering her times as a WASP, ferrying aircraft for the U.S. war effort. After Brian landed, I asked Maryalice if her piloting skills came back to her. “I don’t think it ever leaves you,” she said. —Natalie Holsten, Nampa, ID