Extraterrestrial Outfitter

If you’re planning an off-world vacation, there’s only one name to call: Eric Anderson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Extraterrestrail_outfitter_03012012_1_FLASH.jpg)

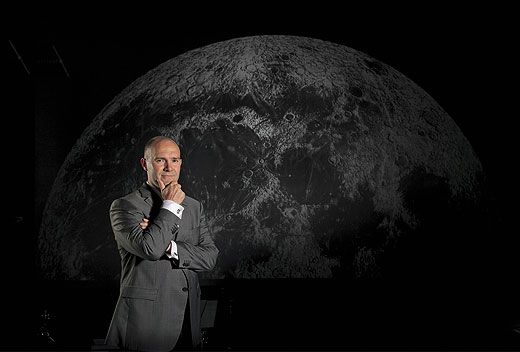

Eric Anderson is clear about his goal. “I’d like to go to space in the next five to 10 years,” he says. “I don’t want to wait.” He sits comfortably on a white leather couch in his office at Space Adventures in Vienna, Virginia, wearing a dark suit and open-collar shirt. A trim, fit man with a closely shaved head, he acts like he’s ready to go tomorrow. But wait he must, until he develops the net worth required to take his dream trip. That may explain why he’s working two high-profile jobs at once: chairman of Space Adventures, and president and CEO of Seattle-based Intentional Software. “Intentional actually could be worth billions and billions of dollars,” he says. “It could be my ticket.”

For the last 10 years, Anderson and Space Adventures have been brokering deals for well-heeled passengers to fly aboard Russian Soyuz spacecraft to the International Space Station. Now that those trips have become more or less routine, Anderson is primed for his own ride. And he’s ready to take Space Adventures to the next level—to the moon.

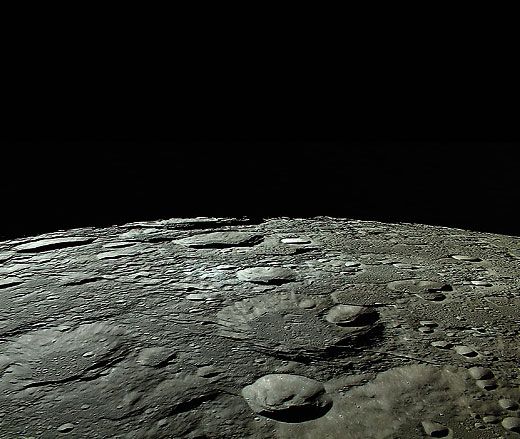

The idea of a private company sending paying passengers into space was outrageous in the late 1990s, when Anderson first floated the idea, but at least professional astronauts were already traveling there regularly at the time. No one has been to the moon since 1972, nor does any government space agency have a solid plan to return. No matter. To Anderson it’s just another challenge, like starting a space travel business in the first place, at the age of 23.

Eric Anderson grew up in the Denver suburb of Littleton, Colorado, the son of an Argentine mother and an American real estate investor. As a boy, he and his family made frequent excursions into the mountains, and he credits the view from the Rockies with sparking his passion for spaceflight. “There is little on Earth that is as beautiful as the night sky in the mountains of Colorado,” he says. There was more to it than that, of course: a steady diet of Star Trek and Star Wars, and a dad who was curious about the natural world. The young Anderson became a math whiz, jumping two to three years ahead of his classmates. By fifth grade he was writing computer programs on early Apple computers, and by his freshman year, Anderson had taken all the math classes his high school offered. He began making plans to attend the Air Force Academy, not far from home. His goal of becoming an astronaut came plummeting to Earth, though, when he was diagnosed with myopia. “That was a really big setback,” he recalls.

It wasn’t until after graduation from the University of Virginia with a degree in aerospace engineering, an internship with NASA, and finally a job writing software code for a company that did spacecraft modeling that another way to reach space occurred to Anderson.

Entrepreneur and fellow space enthusiast Peter Diamandis, who several years later created the X PRIZE to kick-start commercial spaceflight, introduced him to adventure travel operator Mike McDowell, who was sending customers on Arctic voyages and underwater trips in Russian submersibles. Together the three hashed out the initial idea for Space Adventures and ZERO-G Corporation, which would offer rides on aircraft that flew parabolic curves, producing brief bouts of weightlessness. Diamandis provided inspiration and a chunk of financing. “We scraped together $250,000 to start Space Adventures,” says Anderson. In 1998, the world’s first space tourism company was born.

Working with the Russian space program was an obvious choice. The company hoped to eventually send paying customers to orbit, and “there was no way that NASA was going to let anybody buy a flight on the shuttle,” says Anderson. Even if the agency did permit it, the price would be around $200 million per seat—10 times a ride on a Soyuz.

In fact, the door to Russian-backed space tourism was already ajar when Anderson approached it. In 1990, the Soviets had sent Japanese TV reporter Toyohiro Akiyama to space station Mir in exchange for money (the Soviets claimed to have earned $12 million). Akiyama wasn’t a private tourist, but he was no professional cosmonaut either. A year later, British chemist Helen Sharman followed him, having won her seat to Mir in a contest sponsored by a consortium of British companies.

As the Soviet Union broke up, so did its space program, and Russian space organizations like Energia, makers of the Soyuz and Mir, were left to strike their own deals. Chris Faranetta, who would later become a vice president at Space Adventures, recalls those “crazy, crazy times” in the fledgling Russian commercial space business. Faranetta had started his career working on the Lunar Prospector mission at Gerard O’Neill’s pioneering Space Studies Institute. At an international space conference in 1988, he struck up a conversation with officials from Energia, and asked if he could help market their technologies in the West. Three years later, he and Jeffrey Manber, another young American space entrepreneur, opened the offices of NPO Energia in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C., to explore, among other things, cooperation with NASA.

When Space Adventures entered the fray in 1998, establishing good connections in Russia was a must. Company co-founder Mike McDowell already had been arranging for private explorers (including Titanic director James Cameron) to ride in Russian deep-water vehicles. Faranetta joined Space Adventures in early 1999. “What I brought to the table was the connection to Energia,” he says. Sergey Kostenko had led a Russian team competing for the X PRIZE, and was soon “very well known by all the senior space management,” says Faranetta. Marsel Gubaydullin, who had been the official photographer in the cosmonaut village of Star City, also signed on. When Space Adventures client Anousheh Ansari was introduced to him before her 2006 orbital flight, she was told, “Marsel knew everybody in Star City.”

As his team fell into place, Anderson put together deals with Russian service providers for ersatz “space” experiences, like rides to “the edge of space” in a MiG-25 fighter. Space Adventures no longer offers that package, but more than 7,000 people have paid its subsidiary ZERO-G several thousand dollars each to experience weightlessness in a modified Boeing 727.

Always, though, Anderson kept looking for a way that his customers could experience actual spaceflight. “The way the Russians work is, they sort of say ‘No’ to everything,” he explains. “And then eventually they tell you the reasons.” His task, in the early days of Space Adventures, was to ferret out the reasons. It took patience.

“Well, [a Soyuz flight to the International Space Station] might be possible,” he recalls being told by one Russian official, “but we don’t think you could find anybody who could pay enough money.”

“Well, okay,” replied Anderson. “Assume that we would.”

“They’d have to pass the medical exam.”

“Okay, what’s the medical exam?”

Slowly a picture began to emerge: the training that would be required, the approvals that would be needed from the space station partners, the liability waivers the company would have to secure.

Sensing that the ice was about to break, Space Adventures paid Energia $200,000 for a feasibility study, according to Faranetta. The document spelled out in detail what would be required to train, launch, and host a private spaceflight participant on the International Space Station. To be sure, it wasn’t a promise to fly paying passengers. Rather, it was a blueprint of all the obstacles they’d have to overcome first.

“The Russians took this very seriously,” says Faranetta. The study convinced Russian space officials that flying a paying non-professional to the station was safe and, just as important, legal. And it gave Space Adventures something solid to show to potential clients.

Finding that person with the special blend of money, time, and inclination to fly in space was, then as now, a major undertaking. “The challenge is not finding people who are interested,” Anderson says. “Actually, there’re a lot of people who are interested. But will they actually do it next week, or next month, or next year? Everybody’s got an excuse as to why they should wait till later.”

The Explorers Club in New York City provided many of his initial leads. The group’s annual black tie dinner at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel was the ideal place to meet wealthy adventurers. It was there that Anderson met Richard Garriott, video game impresario and son of NASA astronaut Owen Garriott, an early Space Adventures advisor. Garriott the younger also had a strong interest in space, enough to kick in some initial investment in Space Adventures (including the money the company paid for the Energia study). Richard hoped to become customer number one himself, but the collapse of the tech bubble in 1999 wiped out much of his fortune, delaying his trip until 2008. He remains one of Space Adventures’ top investors.

In the early days, Anderson says, “I was always looking for investors, and I always had all my [briefing] stuff with me.” During a trip to Los Angeles in early 2000, he got a meeting with former NASA engineer and now successful money manager Dennis Tito. During a half-hour presentation in Tito’s Santa Monica office, Anderson was typically understated, matter-of-fact, and utterly confident that Space Adventures was going places. “You have a great vision and I love this,” he recalls Tito saying when he was through with the pitch. “But I’m really not interested in investing. I’m interested in going myself.”

Anderson didn’t skip a beat. “Interesting that you mention that,” he said. He just so happened to have in his bag proof that the Russians were practically on board with the project already. Tito was impressed. A few weeks later, he signed a contract as Space Adventures’ first customer.

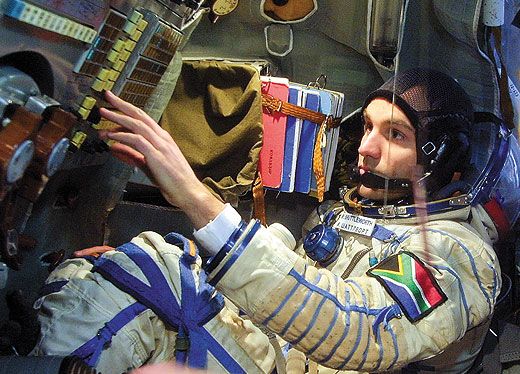

The road to the launch pad was not entirely smooth. Tito had long been looking into other options for a Russian ride to orbit, and when a company called MirCorp, headed by Faranetta’s ex-colleague Jeffrey Manber, offered an earlier trip, to Mir instead of to the International Space Station, Tito jumped ship. Then, when the Mir deal cratered, he came back to Space Adventures. He even weathered the embarrassment of having NASA (temporarily) refuse his training with the cosmonauts and astronauts in Houston. But in April 2001, Dennis Tito became the first person to pay his own way into space.

Success bred success. Space Adventures’ second orbital customer, South African Mark Shuttleworth, called while Tito was still in space. Since Shuttleworth’s 2002 flight, five more customers (including one repeat traveler, ex-Microsoft billionaire Charles Simonyi) have paid Space Adventures to arrange their trips to the International Space Station. Even though the price has gone up (from Tito’s $20 million ticket to around $50 million), Anderson and company have continued to find buyers. In the post-space-shuttle era, Soyuz opportunities have become scarcer, but three seats remain available in the 2013-to-2014 timeframe. Meanwhile Space Adventures is offering the wealthy space traveler an even more deluxe package: a trip to the moon.

It was initially Chris Faranetta’s idea. A student of space history, Faranetta knew the Soviets had sent unmanned Zond spacecraft on circumlunar trips in the 1960s, and that modern Russian launchers, vehicles, and upper stages could, with some modification, do it again. In 2001, around the time of Tito’s flight, Faranetta developed concepts for using the Soyuz-TMA spacecraft to carry two paying passengers and a professional cosmonaut to the moon. Internally, Space Adventures called the plan “Project: Talent.”

It wasn’t until 2005—after the viability of private space travel had been well established—that Anderson and company went public with the idea. Last spring, around the 10th anniversary of Tito’s flight, Space Adventures revealed that it had already sold one of the two seats for a lunar voyage, and was looking to book the second. That’s where the 13-year-old company still finds itself—on the verge, but not quite ready, to pull off a spaceflight that no one, not even NASA, has accomplished in a generation.

DURING MY VISIT to Space Adventures’ headquarters in suburban Washington, D.C., last October, the team was preparing to move down the road to smaller digs. Like a lot of businesses these days, they’re outsourcing some jobs that were previously handled in-house, including some of their event management. Boxes of files and videotapes were lined up along the walls in preparation for the move. A fighter pilot’s pressure suit and a cosmonaut’s reentry suit flanked the vacant front desk. Change was in the air.

These days Anderson puts in more time at his other job on the West coast, working for former client Charles Simonyi. In September 2010, Simonyi hired Anderson to run his post-Microsoft venture, Intentional Software, which aims to revolutionize computer programming by making it more intuitive and user-friendly. In the press release announcing Anderson’s appointment, Simonyi was quoted saying, “Eric is truly an outstanding entrepreneur. He’s one of very few who can take futuristic ideas and make them real.”

Back at Space Adventures, it’s usually president and sales chief Tom Shelley working the phones these days, on the hunt for future space travelers. Shelley, a Briton educated at the University of Manchester, is a marketer by training. “Five years ago I knew nothing about space,” he says. That’s partly what makes his pitch credible. It all sounds so reasonable coming from him. On any given morning, he’s on the phone during his half-hour commute, talking to a possible client overseas. To find prospects, he connects with high-end travel agents, organizers of yacht shows, and others who cater to the adventurous one percent. He also spends a lot of time at conferences, like the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and the Forbes Global CEO Conference.

“There’s no standard pitch,” he says. Sometimes the direct approach plays best: “Have you ever considered going into space?” The reactions, he says, range from “ ‘I would absolutely love to, but my wife would kill me’ to, you know, just bursting into laughter.”

Chris Faranetta has left Space Adventures (he now works for a fusion energy technology company called HyperV, in Virginia), but the company holds steady at about 20 employees. Sergey Kostenko still heads the Moscow office (while running a side business called Orbital Technologies, to market stays on a yet-to-be-built orbital hotel), and Marsel Gubaydullin, the former Star City photographer, is still director of operations in Moscow.

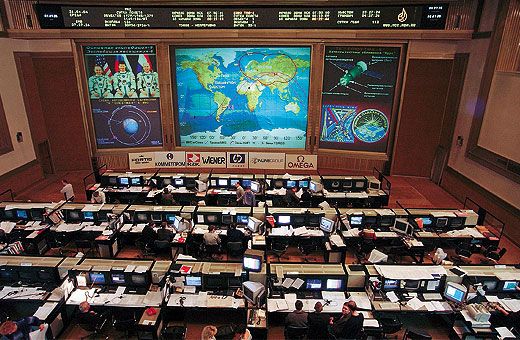

The lunar voyage is by far the most exciting thing on their horizon. The mission plan—which has progressed from Faranetta’s early concepts to a detailed, Russian-produced study similar to the one created for space station visits—now calls for a liftoff from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan with two passengers paying at least $150 million each, along with a professional cosmonaut as spaceship commander. The crew will ride in a modified version of the Russian workhorse, the Soyuz-TMA.

Another rocket, a Proton, would launch an additional habitat module designed specially for the mission, which will double the living space and carry more supplies, plus a Block-DM upper stage, normally used for boosting communications satellites to higher orbits. These pieces will link together in Earth orbit, and the Block-DM will fire to send the combined Soyuz–habitat module into deep space.

Three and a half days of travel will bring the crew around the far side of the moon, the face that Earthlings never see. The crew will skim the mountaintops without going into orbit, swing back around to the front side, and then head home to Earth—a figure-eight trajectory similar to the one traveled by the crew of Apollo 13. After another three and a half days, the crew’s Soyuz reentry module will hit Earth’s atmosphere and parachute down to the Kazakh steppe.

Sounds fantastic. And feasible, according to Space Adventures and its Russian advisers. But it will certainly be a stretch. “What I would be most worried about is the entry,” says Ken Bowersox, a former NASA astronaut and Soyuz veteran who now works for SpaceX. “The key thing is making sure they hit the Earth’s atmosphere at just the right angle.” Enter too shallow, and the crew risks bouncing back out into space, never to return. Come in too steep, and the ship would disintegrate from the intense heat of reentry.

Other aspects of the lunar trip should be more straightforward, according to Bowersox. “If you look at the other things that have to be done, and the experience the Russians have with life support systems, with structures, with engines that work in space, they’ve demonstrated a lot of capability…that should transfer directly to being able to go out, around the moon, and back.” And, he can’t resist adding, “I’d love to do that flight. Seven days—man, you can’t buy a vacation like that. Seeing the moon up close. Get to see the Earth rise on the other side. That’s quite an experience.”

Former astronaut Jim Voss, who was onboard the space station during Tito’s 2001 visit, points out that a manned lunar trip, which the Russians have never done, “is harder than going to [Earth orbit]. I believe they are morally obligated to demonstrate the safety of their system before selling seats.” Indeed, Space Adventures and its Russian partners plan to fly at least one full-up test flight to the moon and back. Anderson says this will take place a few months to a year before the actual mission. They have not decided whether the test flight will have a crew.

Leroy Chiao, another former space station astronaut who has ridden on the Soyuz and, more recently, has worked to develop commercial uses of Russian space hardware, says he wishes Space Adventures well. But he raises a political question: Is the traditionally conservative Russian space establishment willing to take on such an ambitious project right now? This is not like sending private tourists to the space station, using well-established vehicles and procedures. “This is much more speculative, because it requires that money be put down for development work on new hardware, or to integrate existing hardware that hasn’t been integrated before.”

None of these concerns is likely to surprise Anderson. And he’s shown persistence in the face of adversity before. When Russian space doctors told Greg Olsen, Space Adventures’ third spaceflight participant, that he couldn’t fly in space due to an irregular heartbeat, Anderson sprang into action, enlisting a former NASA chief flight surgeon to persuade them to change their minds. “Obstacles? There were plenty,” Olsen wrote later. “But there’s always a way around them, if you just look long enough and argue hard enough. Eric Anderson has become a master at this, out of sheer necessity.” Olsen flew to the space station as planned in October 2005.

Space Adventures won’t reveal who has reserved the first ticket for its lunar mission until passenger number two signs. Movie director James Cameron, who has been angling to get into space for more than a decade, is said to be a likely prospect, but neither he nor the company will comment. In a recent interview with PBS science reporter Miles O’Brien, Anderson described the ideal private space traveler. “It’s not something like climbing Mt. Everest, or that requires a great deal of physical fortitude, or being in shape like running a marathon,” he said. “Those things are actually much harder. It’s something that requires a few months of your time and some optimism about the future. It’s really more an intellectual venture than it is a physical venture.”

The candidate almost certainly has to be a billionaire, or close to it. Fortunately for Anderson, there are currently some 1,200 billionaires in the world, 100 in Russia alone. (Manber, the veteran of MirCorp and other commercial space dealings, thinks the ideal candidate for the lunar mission might be someone from a country that has never had its own space program, or a Russian looking to help shore up his country’s space industry.)

Once that second customer puts down a deposit, says Anderson, metal will be bent at Energia, training will proceed, and preparations for the test flight will begin. From that point to the first tourists swinging around the moon: about four years.

If the first moon mission is successful, Anderson sees many more lunar flybys in Space Adventures’ future. In fact, he hopes to make the second or third trip himself. And from there, he says, a lunar orbital mission can’t be far behind. As for the ultimate adventure—walking on the moon—it’s not on the immediate horizon for Space Adventures or its Russian partners. Richard Garriott figures a commercial manned landing mission would cost more than a billion dollars. “We think the market for people who can afford to land themselves on the moon and get back off is pretty close to zero,” he says. Purely from a business point of view, it doesn’t make sense. Yet.

On the day of my visit to Space Adventures, Anderson had flown in from Seattle the night before for meetings at the office and on Capitol Hill. He hit the ground running, calling a contact in the car on the way in, looking for information about a billionaire prospect with whom he would meet in three weeks. His overnight bag and briefcase stood at the ready near his desk; he would jet back to the West Coast later that night. Somehow, space didn’t seem too far beyond.

Michael Belfiore is the author of Rocketeers: How a Visionary Band of Business Leaders, Engineers, and Pilots Is Boldly Privatizing Space (Harper, 2008).