The First Aerial Combat Victory

Airplane vs. airplane over France in 1914

:focal(380x186:381x187)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/79/a079d4fd-012d-4e55-be10-6919ca0eb480/frantz_and_quenault.jpg)

By the time World War I began in the autumn of 1914, airplane engineers and pilots had been thinking about aerial combat for years, even if nobody had yet seen what would later be called a dogfight.

Aviation historian Harry Woodman considered a 1913 incident from the Mexican Revolution to be the “first aerial duel in history between two airplanes.” American pilots Phil Rader and Dean Ivan Lamb, who were on opposite sides of the conflict, fired revolvers at each other while airborne. Neither one got hit.

The first aerial battles of World War I were variations on that same theme. French aviation historian David Méchin ticks off a list of “firsts” that all happened within a few weeks of each other in 1914. On August 25, Roland Garros and Lt. de Bernis became the first flyers to damage an enemy aircraft. Flying a Morane Parasol, they shot at a German airplane, which escaped in a dive, although one of the two men onboard was wounded. On September 7, Russian Pyotr Nesterov was the first pilot to destroy an enemy airplane, but he did it by ramming his Morane into an Austrian Albatros. Both air crews died as a result.

Then, on October 5—100 years ago tomorrow—French pilot Sgt. Joseph Frantz and his mechanic/gunner, Louis Quénault, shot down a German biplane near Reims to record what is considered the first official aerial combat victory. Méchin tells the story in detail in this month’s edition of the French aviation history magazine Le Fana de l’aviation.

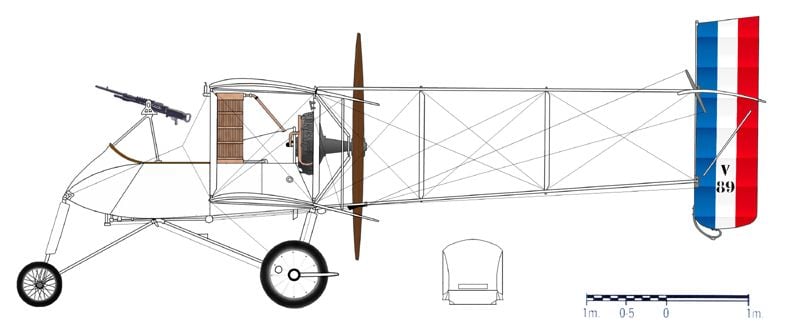

The key difference in this encounter was the 8-millimeter Hotchkiss machine gun fixed to the front of the French Voison biplane. Mounted guns would soon be standard equipment for WWI combat aircraft, but when the head of Frantz’s V 24 escadrille had requested them for his squadron, he was at first ridiculed for his “Jules Verne” idea.

The Hotchkiss proved its worth when Frantz got into a chase with a two-man German Aviatik biplane during a morning bombing mission near the village of Jonchery-sur-Vesle, not far from the trenches. Frantz recalled later that he saw the passenger in the enemy airplane ahead of him take out a rifle as Quénault fired a few dozen rounds, finally hitting the Aviatik’s fuel tank. The Germans went down, trailing smoke, and crashed in a swamp. The pilot, Wilhelm Schlichting, had been killed by a bullet. His observer, Fritz von Zangen, died in the crash. Frantz, who lived to the age of 89 (he died in Paris in 1979), would later recall his enemies’ deaths without satisfaction, according to Méchin. After the French pilot landed and arrived at the crash scene, souvenir hunters were already going through the wreckage, and someone handed Frantz a picture of one of the Germans. He handed it back moments later.

The victory was applauded in the French press, and Frantz was awarded the Legion of Honour, while Quénault got the Médaille militaire. Part of the reason for their fame is that there had been so many witnesses. According to an account in the Daily Telegraph reprinted in Flight magazine on October 16, 1914, “All the French troops on the spot forgot the danger of passing shells, and jumped out of the trenches to watch the air fight.”

The age of aerial combat had begun.

Frantz appears in this video clip (at about the 10:30 mark) reminiscing about the incident many years later.