The First Arctic Flight—in 1914

A little-known Polish aviator got there more than a decade before Byrd and Amundsen.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/d0/c4d0a1cf-b0d5-4f1c-b57a-7d4848788704/nagorski_and_crew.jpg)

Aviation’s first decade coincided with another great adventure—a race, almost a frenzy, to reach the poles of the Earth. It was natural for balloons, airships, and eventually airplanes to be part of that quest, but as of 1914, no one had yet managed to fly an airplane in the stormy, frigid conditions above the Arctic Circle. In April of that year, Robert Peary, who had reached the North Pole (or very close to it) in 1909, could only speculate that aerial trips to the far north “will be simple matters of course in five years’ time.”

He didn’t have long to wait. In August and September of 1914, a 26-year-old Polish aviator named Jan Nagórski became the first to pilot an airplane successfully in the Arctic, covering some 650 miles in five flights totaling more than 10 hours, and venturing as far north as 76 degrees latitude. He never reached the pole, but he pioneered techniques for Arctic flying that later explorers, including Richard Byrd and Roald Amundsen, would find useful. Even so, Nagórski’s story was all but forgotten, even in his own country, for most of his life.

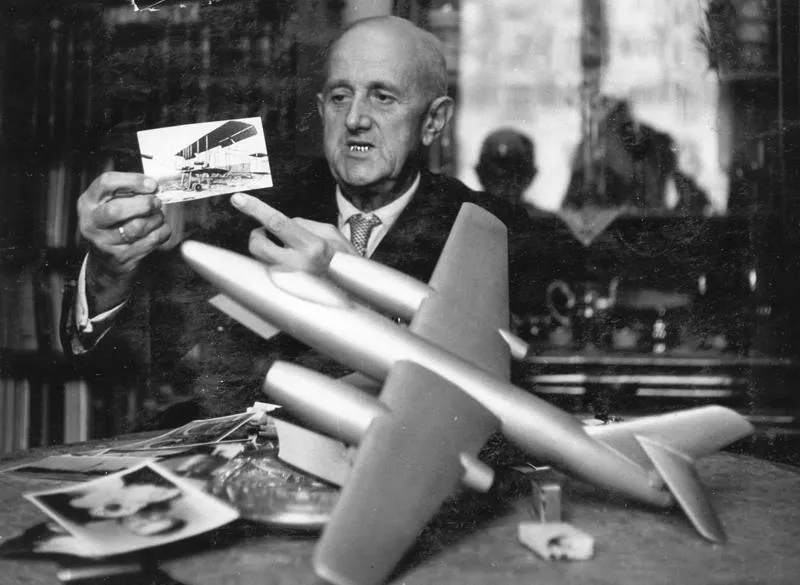

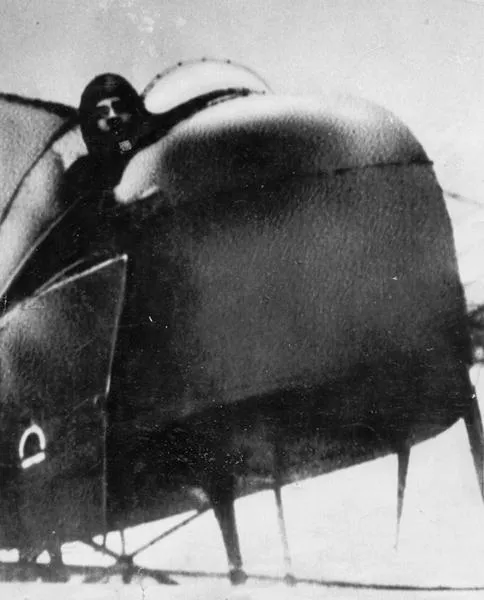

Born in a village on Poland’s Vistula river in 1888, Nagórski was caught up in the excitement of early aviation as a young man, and graduated from flight training school as a military pilot for the Russian navy in 1913 (Poland was then part of the Russian empire). A year earlier, three Russian Arctic expeditions had all gone missing, and Nagórski’s commander at the Chief Hydrographic Administration asked the young officer if airplanes might be used in the search. The answer was yes, and Nagórski was named the pilot. He was allowed to pick the airplane for the expedition, and in May 1914 went to the Maurice Farman factory in Paris to supervise construction of his craft: a biplane mounted on floats, with an air-cooled Renault engine, room for two people, and a top speed of about 65 mph. By mid-August he and the mechanic who would accompany him, Yevgeniy Kuznetsov, set sail for Novaya Zemlya, a remote island above the 70th parallel where the missing explorers were last seen.

In five flights ending on September 13—100 years ago tomorrow—Nagórski skirted the northwest coast of Novaya Zemlya, while the ship Andromeda stayed anchored nearby as a base, both crews searching for the lost explorers. They never found them, although they did discover notes and caches of supplies left by one of the expeditions.

Nagórski did learn plenty about operating a wood-and-canvas biplane in freezing Arctic conditions, however. On one fog-bound trip, the Farman’s compass stopped working. On the second flight, Kuznetsov started stamping his feet to ward off the chill, and stamped so hard he put his foot through the cabin’s thin wooden floor. On another flight the engine conked out, fortunately still within site of the ship (Nagórski ranged as far as 60 miles from the coast over the Barents Sea). The aviators were able to scout floating ice conditions from the air—a great value for ships in the area—and correct flaws in existing maps of Novaya Zemlya.

Nagórski returned to Russia with a list of recommendations for future Arctic aviators: paint your airplane red so it stands out in the whiteness; take along spare floats and propellers (he broke two propellers in the span of a month); and watch out for changes in wind speed, which are frequent in the far North. Most important of all, he came back confident that airplanes could reach the North Pole, as Byrd and Amundsen proved more than a decade later.

As for Nagórski, he went on to fight in World War I, and was shot down and reported killed in action over the Baltic in 1917. He had in fact survived, but here began his descent into obscurity (he finally did achieve recognition for his Arctic flights in the two decades before his death in 1976). In 1918 Nagórski made his way back to Poland, eventually taking a job as an engineer in a sugar factory. During World War II he ran a small antique store in Warsaw that doubled as a secret storage center for bomb-making chemicals used by the Polish resistance. After the war he settled into an office job, but always kept up his interest in Arctic exploration.

In the winter of 1956 he attended a public meeting where the speaker, in recapping the history of polar expeditions, happened to mention one Jan Nagórski, a Russian who had made the first Arctic flight but had died in 1917. The audience was surprised when an elderly man stood and said, “I’m sorry, but I was not Russian. And I absolutely do not feel dead.” Newspapers took up the story, and before long Nagórski was famous in his own country and throughout the Soviet Union.