The First Airliner to Vanish

In 1930s aviation, airline passengers took the same risks as record-setting adventurers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/18/b918dc90-f4bd-4acd-bb1a-e658ebc3933b/09c_sep2017_southerncloudoversydney.jpg)

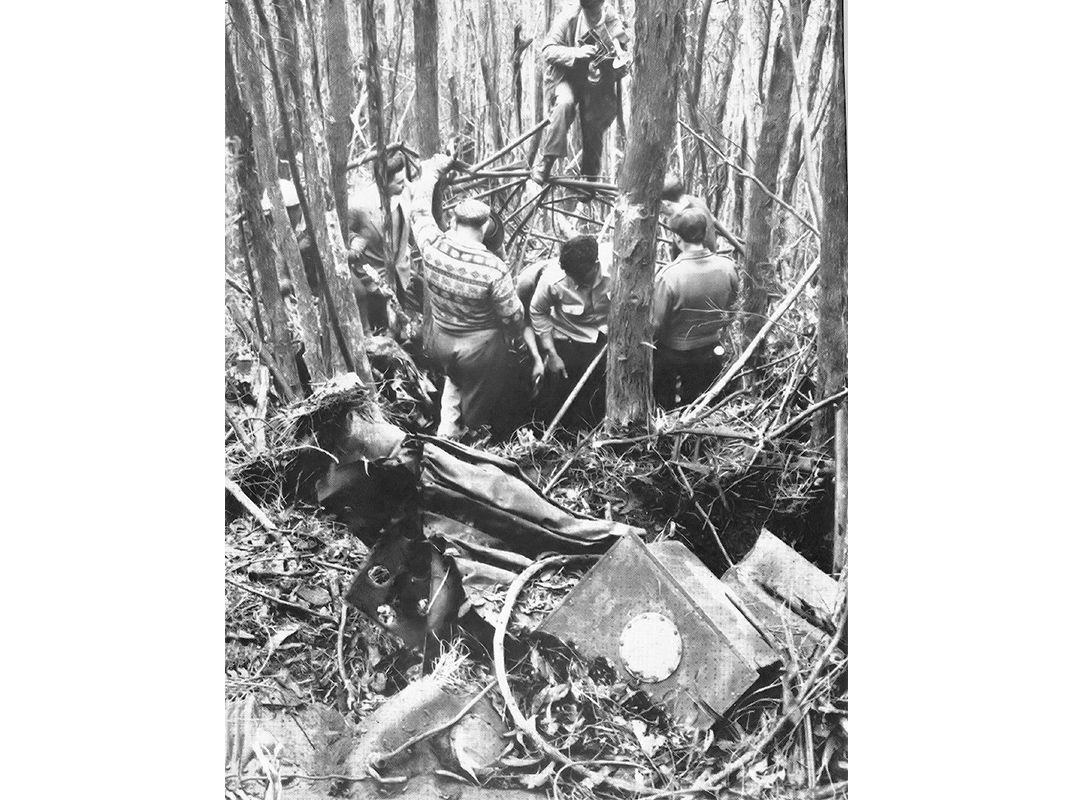

On a wooded slope of the snowy mountains in Australia’s Kosciuszko National Park, located about halfway between the coastal cities of Sydney and Melbourne, an odd memorial is nearly hidden among the trees. A four-foot-tall sheet of wrinkled aluminum, embossed with eight names, marks the site of a 1931 airplane crash that killed two pilots and six passengers. Strewn about the aluminum marker is the wreckage of the Avro Ten tri-motor Southern Cloud.

It’s easy to forget, in this era of reliable weather prediction and wireless communication, that air travel began before the routine use of radio or any means of communication between the air and the ground. Passengers flying even short distances couldn’t know what awaited them along the way. Southern Cloud, an Australian National Airlines tri-motor bound for Melbourne, departed Sydney in rain on March 21, 1931, and flew into history as the first airliner to disappear.

Australian National Airways (ANA) was among the earliest commercial airlines, the creation of aviation pioneers Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm. Kingsford Smith was the Australian Charles Lindbergh, a record-setting pilot and aviation evangelist. Ulm, Kingsford Smith’s trusted partner, accompanied him on many historic flights, including the 1928 10-day crossing of the Pacific from America to Australia in a Fokker tri-motor named the Southern Cross.

The Southern Cloud was a licensed production version of the Fokker on which the Southern Cross was based, but there was a critical difference between the two. For their trans-Pacific journey, Kingsford Smith and Ulm had two-way radio equipment and were in touch with ships and shore stations. The Southern Cloud, like most airliners of the day, had no radio.

On the day of its disastrous flight, Captain Travis Shortridge and the pilot-engineer apprentice, Charles Dunell, guided the tri-motor down the runway at Sydney’s Mascot Aerodrome and into the sky with six of eight passenger seats occupied. Among the passengers were Bill O’Reilly, a young accountant who was expanding his practice in Melbourne; Elsie May Glasgow, who was flying home after a holiday with her sister in Sydney; and American Clyde Hood, a theater producer. For a weather forecast, Shortridge relied on that day’s Sydney Morning Herald, which had compiled its weather report the night before.

The airplane had been in the air for an hour when an updated meteorological report reached the airline’s headquarters in Sydney. The Southern Cloud was headed for driving rain, strong winds, low clouds, and cyclonic conditions. The only thing anyone on the ground could do, however, was worry. With no radio, the Southern Cloud was unreachable.

When the airliner failed to arrive in Melbourne, a massive search began. ANA flights were suspended so that the line’s pilots and aircraft could scour a broad area along the Cloud’s expected flight path. The Royal Australian Air Force helped search for 18 days. ANA carried on for several weeks longer. From far-flung areas, prospectors, schoolchildren, shepherds, and even a community postmistress reported seeing or hearing the missing airliner.

In April 2016, I visited the historical society museum in Tumbarumba, a small New South Wales town on the western edge of the Snowy Mountains. In the museum, a comprehensive display on the Southern Cloud features a map showing the locations of the reported sightings.

“It’s here, it’s there, in all the places between Sydney and Melbourne,” said historical society president Ron Frew, who with his wife Catherine created the map. “Most had to be completely false.” The airplane wouldn’t have been carrying enough fuel to travel as far as most of those locations.

This part of the story sounded familiar to me, having spent most of the spring of 2014 in Kuala Lumpur, covering the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH 370 for ABC News (“What Went Wrong on Flight MH 370?,” Sept. 2016, an excerpt from the author’s book The Crash Detectives).

After MH 370 vanished, we heard from a fisherman off Malaysia’s east coast, an oil worker in south-central Vietnam, and residents of the Maldives, all of whom reported seeing a jetliner in the early morning of March 8, the day MH 370 disappeared. Last January the search was finally abandoned, after a survey of more than 46,000 square miles. Despite searches with sonar, the site of the aircraft on the sea floor was never located. Why not?

The best response I’ve heard comes from a book about the Southern Cloud published in 2010 by the late Macarthur Job, Into Oblivion: The Southern Cloud Enigma. Trying to find the Avro Ten in a 100,000-square-mile mountainous area, he wrote, was like looking for “one needle in ten haystacks.” But miraculously, on October 26, 1958, 27 years after the Southern Cloud had disappeared, a hiker stumbled onto just the right haystack.

Tom Sonter, a 26-year-old construction worker enjoying time off from his job at a government-sponsored hydroelectric project, was walking in the densely forested area now known as the Kosciuszko National Park. An energetic hiker and photography buff, he was scouting for a shortcut back to camp when his attention was drawn to a mound of earth that looked out of place.

“There was a small piece of steel poking through the leaves of the saplings,” says Sonter, now 85. The metal had the unmistakable shape of an airplane tail. “I didn’t speak a word or make a sound, but my brain yelled out, ‘It’s a plane.’ ”

At the time, the Southern Cloud meant nothing to Sonter, who hadn’t even been born in 1931. Among those he told of his find, however, were several who remembered the quarter-century-old mystery. Soon, Australia’s senior inspector of air safety, A.H. Jim Green, was on the scene, arriving around the same time as the souvenir hunters who absconded with anything they could carry.

In the years after the airplane’s disappearance, there was so much speculation about what had happened that it was hard to separate facts from folklore. The 1934 film Secret of the Skies, which was based on the mystery of the Southern Cloud, suggested that one of the passengers had been carrying the proceeds from a bank heist.

As far as the crash investigation, though, the resolution of the Southern Cloud mystery was notably anticlimactic. After examining the wreckage, including the way the airplane’s metal frame had telescoped into itself, Inspector Green came to a conclusion not much different from what was suspected from the start: Captain Shortridge had unknowingly flown into terrible weather with winds much stronger than he realized. Even keeping a heading to stay on a course north of the Snowy Mountain range, the airplane was pushed at least 25 kilometers (16 miles) south—right into the mountains.

“This was bad weather with descending air currents dragging them down toward the tree line, possibly iced-up engines not performing properly. Everything was stacked against them,” said Gary Crowley, an Australian pilot and a member of the Airways Museum and Civil Aviation Historical Society in Melbourne, which traces the development of Australia’s civilian airways system.

Crowley, like Green, believes that Shortridge probably realized at the last minute that the mountain was looming and tried unsuccessfully to turn around.

“We look back at this through the lens of today and the way we do things today,” said Phil Vabre, the historical society vice president. He had joined an impromptu conversation that started at the display case where a few pieces of the Southern Cloud are exhibited. “Look at it through the lens of their time,” he reminded me.

Shortridge and the other pilots flying for ANA trained for instrument flying using the same techniques Kingsford Smith relied on to cross oceans. They would assess outside conditions like the weather and the wind, then add aircraft information like speed and direction and calculate their position based on elapsed time. Whenever possible, the pilots would try to use ground references. Sometimes that meant descending without being certain of what was below.

As with all airline tragedies, the loss of the Southern Cloud had repercussions. After another crash in November that year—the Southern Sun went down on the Malay peninsula in south Asia—ANA ceased operations.

Australia’s Air Accident Investigation Committee had no evidence in 1931 for determining the cause of the Southern Cloud crash, but still the committee was proactive, recommending that passenger aircraft be equipped with radio equipment. It took some time. Not until 1934 was an Australian airliner able to use wireless communications: The first was a de Havilland DH84 Dragon flying with Tasmanian Aerial Services. (In the United States, the first radio-equipped control tower began operations at Cleveland Municipal Airport in 1930. By 1932, most U.S. airlines carried radio equipment.)

The human remains found at the Southern Cloud crash site were buried in the town of Cooma, where the hydro-electric development project had its headquarters. In 1962, the aircraft’s engine casings and some other large pieces of wreckage were assembled in a memorial pavilion, designed to resemble an airplane’s wing and installed in one of the town’s parks.

That might have been the last of the Southern Cloud story, except that the crash site wound up as a day-trip destination in a hiker’s guidebook. In 1984, the Frews, then schoolteachers and the parents of two young children, read about the site and decided to make the trek to the final resting place of the world’s first airliner to disappear. “We didn’t know much about the plane other than it was in a guidebook,” Catherine Frew said, but the family walked to the site.

In their 48 years of marriage, Ron and Catherine Frew have written 10 books together on a wide range of subjects, from mountain biking to World War I history. When Ron Frew became the president of the Tumbarumba Historical Society in 2004, he and Catherine turned their attention to finding out more about the Southern Cloud and the people affected by the disaster.

“Our view of history is this: People are important,” Catherine told me. “It’s not just dates, it’s the people involved and their stories.” The Frews have spoken to daughters and great-nieces and -nephews of those killed in the crash and to those who were around when the crash site was discovered, and of course to Tom Sonter. They have organized dinners and memorial gatherings, and in 2011 they arranged for those descendants (who were physically able) to make the climb to the crash site.

Ron Frew boasts that the Southern Cloud exhibit at the Tumbarumba Historical Society museum is home to the largest number of artifacts. That collection continues to grow as residents of the area find evidence in sheds and barns of the souvenir hunting that went on after the lost airplane’s discovery.

The day after my visit to the museum, the Frews took me to the crash scene. From the parking lot in Kosciuszko Forest, the foot trail is a seven-mile paved surface leading to a 30-minute, hand-over-hand scramble up steeply pitched earth. I’m not sure anyone making the climb without a guide would even see the rusty wreckage, camouflaged as it is by forest growth. What does stand out, however, is the four-foot-tall sheet of aluminum.

Pink porcelain flowers, the type sometimes seen on gravestones, are badly worn but still perched on the lower left side. When I was in Australia, this memorial was the last mystery associated with the Southern Cloud. “Nobody seems to know who or when that was put there,” Catherine told me. She saw it in 1984 when she and her family first made the climb. But earlier visitors knew nothing about it. While no one today knows who constructed and installed it, I learned that the person who almost certainly financed it was Australian aviation adventurer Dick Smith. In 1983, Smith had just finished the first round-the-world solo helicopter flight, which would land him in the record books and burnish his already established reputation in Australia.

“I’m sure someone asked if I’d put some money towards it and I think I gave $1,000, but for the heck of me I can’t remember who did it or anything more than that,” he said.

Smith was just 14 when Sonter found the Southern Cloud, but he remembers hearing the news. He was barely 20 when he visited the memorial pavilion in Cooma. “I’ve always had a fascination with it,” he said. He was among those present in 2008 for the opening of another memorial, a roadside overlook with an expansive view of the mountain range that claimed the flight.

On the 85th anniversary of the crash and one month before my visit, Tom Sonter made the climb to the wreckage for what he estimates was his 12th time. Later he sent a letter to the local paper expressing admiration for the Southern Cloud passengers. “Governments have excelled in building airplanes and rockets for war and defense, putting men on the moon and cars on Mars,” he wrote. But the role of the courageous early fliers, including passengers, goes underappreciated. Without them, Sonter said, it would not be “possible to fly to the other side of the world in a day conquering the tyranny of distance.”

Today’s safety record is almost miraculous, but when airplanes disappear into areas of geographical remoteness, the tyranny of distance can still prevail.