Five Reasons to Like NASA’s Asteroid Retrieval Mission

So it’s not the Moon or Mars. Get over it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/50/85501c96-cbe8-426c-a777-099d8bf6a61f/asteroid_retrieval1_946-710.jpg)

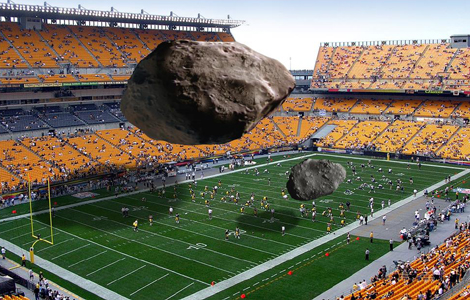

This week NASA announced plans to capture a small asteroid in 2019 and bring it back to the vicinity of the Moon for later study by astronauts. It’s a good idea, for several reasons.

It’s of real importance to society.

The asteroid threat is sometimes overhyped, and it’s no wonder politicians don’t consider it an emergency when the last Extinction Level Event (to borrow a term from Deep Impact) happened 64 million years ago. Still, the fireball over Chelyabinsk in February demonstrated that even a small space rock can do damage, and hinted at even scarier scenarios. The rock that NASA plans to retrieve would be just half the size of the 60-foot Chelyabinsk object, small enough to burn up harmlessly if it entered our atmosphere. But learning to deflect or move even a mini-asteroid should give us valuable experience.

The 2012 DA14 asteroid that bypassed Earth last February compared to the (smaller) object that entered the atmosphere over Russia on the same day. The rock to be retrieved by NASA would be half the size of the smaller asteroid. (Art by Michael Carroll, courtesy B612 Foundation)

Public support for asteroid research is a no-brainer, yet NASA has had trouble allocating even a few million dollars a year (in an $18 billion budget) for a comprehensive search using a modest, space-based telescope. This new mission would help get the hunt started, because it requires an inventory of even smaller objects than we’ve tracked in the past.

Meanwhile, NASA still struggles to find a compelling destination for future astronauts that will sell with the general public. Expeditions to Mars or setting up an outpost on the Moon are fascinating projects, but hardly essential, and many taxpayers still consider them frivolous. Understanding asteroids and learning how to alter their course, on the other hand, are critical to humanity’s ultimate survival.

It advances space technology.

A mission that sounds straightforward, and is expected to cost no more than NASA’s latest Mars rover, would nonetheless require several new technologies that could also be applied to other projects. Solar electric engines for the unmanned tug that retrieves the asteroid can be used on future planetary spacecraft. Robotic tools for snagging an “uncooperative” target like a tumbling asteroid might also be used to clean up space debris or refuel satellites in orbit. After the rock is retrieved, astronauts will have to learn to live and work in what’s called cislunar space, something they’ve never done. In short, there’s plenty of cool and useful technology in an asteroid retrieval mission.

It sends astronauts farther than they’ve ever gone.

Does human spaceflight have a future? In 2013, the answer is not obvious. The technologies of robotics and telepresence are advancing far faster than rockets and space capsules, which are still spinning off ideas developed in the 1950s. Those who doubt that humans will ever be content to explore deep space virtually, as opposed to going there in person, should consider Skype and Oculus Rift. Behaviors deeply embedded in human culture are changing before our eyes. Military forces are rapidly evolving from a centuries-old model of flesh-and-blood warriors facing off on battlefields to drones fighting drones. Why should space exploration be any different?

This may not, in fact, be the last hurrah for old-school (human) astronauts. But choosing a just-over-the-horizon destination like the lunar far side, while reviving some of the old Apollo mojo, will help us decide whether to continue sending people farther out into the solar system.

It encourages cooperation.

Groups including the B612 Foundation already are working to characterize the threat of larger incoming asteroids (“city killers” upwards of 100 feet in size), while others have announced plans to mine smaller rocks. NASA might be able to leverage these private ventures to keep its own costs down and encourage more players in the space business.

Within the agency itself, an asteroid retrieval mission would demand closer collaboration between the astronaut program and the science side of the house than at any time since Apollo. Meanwhile, partners in the International Space Station, who’ve shown only polite interest in the Moon or Mars, might be more willing to join in a smaller-scale mission with obvious benefit to all nations.

It’s doable.

Maybe the biggest advantage of all.

Every so often, a U.S. President (Bushes 41 and 43 most recently) proposes a grandiose go-to-the-Moon or –Mars scheme, which quickly peters out when everyone realizes, once again, that it costs way too much. Space advocates with long memories might be forgiven if they no longer expect Charlie Brown to kick the football.

Today the economic situation is worse than at any time in the space age. With millions unemployed and uninsured, and with public and private debt skyrocketing, no politician is about to suggest an expensive mission to the moon or Mars. Sorry, that’s not strictly true. Those representing districts with NASA centers will. But don’t expect many others to join them.

That leaves NASA building a new rocket (the Space Launch System) and new vehicle (Orion), with no obvious place to go. Space agency managers rightly asked themselves what they could realistically do with the tools and money on hand, in a relatively short time. And the asteroid retrieval mission is what they came up with.

Some will say that grabbing a space rock – a tiny one at that – is not ambitious enough, not worthy of the nation that launched Apollo. “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp,” so this argument goes. Maybe. But while Robert Browning’s advice may be good for an artist, it can lead to frustration and failure for engineers and accountants.

So here’s a more pertinent line from the same poem: “Less is more.”

Let’s do something we can actually accomplish. And let’s get on with it.