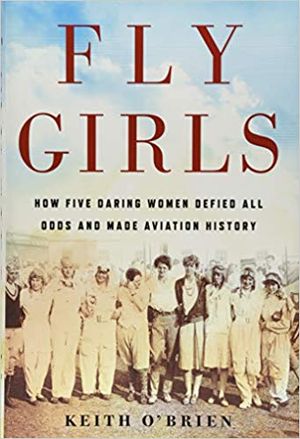

Fly Girls

During aviation’s golden age, female pilots struggled to participate.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/a0/97a01c63-be27-4b93-982e-3a67c48c15d3/louise_thaden_edited-1.jpg)

In the 1930s, air racing was a wildly popular spectacle. While men were encouraged to race, women who wanted to fly the daring cross-country routes often experienced discrimination. Former Boston Globe reporter Keith O’Brien has written Fly Girls, a new book that profiles five female pilots willing to risk their lives to advance the sport: Florence Klingensmith, Ruth Elder, Amelia Earhart, Ruth Nichols, and Louise Thaden. O’Brien spoke with Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in November.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

O’Brien: I was on an airplane, of all places, in June 2016, when I read a stray line in a different book about all an all-female airplane race in 1929 that had featured Amelia Earhart. The line caught my attention because I had never heard of Earhart racing airplanes—or any all-female airplane race. So I started poking around on it, doing what journalists do, pulling the string and following it where it led.

How did the women handle discouragement?

The sexism was blatant—and everywhere. Male pilots belittled the women. They didn’t want them flying in the air races—and the women knew it. The press often disparaged the women too, with demeaning comments and headlines. In order to keep going, Louise Thaden said: “It took dedication—and the courage to accept defeat, after defeat, after defeat.” But at least they had each other. That was one thing that really struck me about these women: Even though they were rivals in the sky, they were friends on the ground.

Did newspaper reporters give equal coverage to the women’s air races?

The women, at least in the early days, sometimes attracted more attention and more headlines than the men. Because there were so few women flying—and even fewer of them racing airplanes—the female pilots were unusual, different. People just had to see that—they’d push to get close to the women in wild mobs. During the first women’s air race—from Santa Monica to Cleveland in 1929—tens of thousands of people waited at small-town airfields across America, hoping to catch a glimpse of the women, shake their hands, or get their autographs. So by the time the women reached the finish line in Cleveland that week so many Americans had seen them, heard them on the radio, or read about them in the newspaper that they had become some of the most famous aviators in the country—male or female.

Based on your research, what is the most egregious example of sexism one—or all—of them faced?

Sadly, it’s easy for me to answer this question. In September 1933, air race officials invited one woman to race against the men in a 100-mile competition around pylons placed on the ground in a triangular course in suburban Chicago. Her name was Florence Klingensmith, and she was one of the most accomplished female air racers of the time. That’s why the men invited her to compete. And, by all accounts, Klingensmith flew a beautiful race, better than most of the men. But her plane that day—a Gee Bee Super Sportster—failed her. Everyone saw it happen. The right wing, buckling under the strain of the speed, fell apart in midflight, and Klingensmith crashed and died.

When this happened to a man—when a man crashed and died in the air races—he was treated as a hero, and sometimes given grand tributes right there on the airfield. Klingensmith didn’t get even the most basic, decent human respect. Investigators and reporters blamed her death not on the plane, but on what they described as her own “weakened condition.” During the autopsy, it was determined that Klingensmith was on her period at the time of the crash. She was menstruating. Or, as one newspaper put it, she was “ill.” And they used this detail to criticize Klingensmith, doubting her skills and her motivations. I was infuriated when I first discovered this during my research. I’m still infuriated now.

Florence was a great and daring woman. She sacrificed everything to do the thing she loved. Then the men blamed her for what happened in Chicago. And then—on top of everything—we forgot her. History erased her. All of that, to me, is wrong.

Why was Amelia Earhart so famous while the other four women never became well-known?

Let me make one clarification: All the characters in Fly Girls were well-known in the 1920s and ’30s. They were all famous—at the time. Stories about Ruth Elder, Louise Thaden, Ruth Nichols, and Florence Klingensmith filled American newspapers. At times, some of these women were—objectively speaking—even more famous and more accomplished than Earhart herself.

In the 1930s, this began to change. Earhart flew the Atlantic solo, then the Pacific solo, and she really did become, at this point, the most famous of them all. But she didn’t do it alone. In 1931, Earhart married the man who initially discovered her—New York publishing magnate George Putnam. He had both means and money. And his publicity machine would help keep Earhart in the news, giving her opportunities the other women didn’t have.

That shouldn’t take anything away from Earhart’s accomplishments. She was—and is—an American icon, who risked her life to prove what she, and other women, could do. But her connections to Putnam help explain why we remember her and have forgotten the others. And of course the mystery of what happened to her in 1937 only deepens our fascination.

What is the most surprising thing your research uncovered?

I am not an aviation historian: I’m a journalist. So I came to this story with a blank slate. And because of that, many things were surprising to me. But one of the things that shocked me the most was our tolerance for death and disaster. In the 1920s and ’30s, people crashed in the air races all the time. Pilots often died right in front of the grandstand. And those who attempted to fly across the ocean in the days of Lindbergh and Earhart often failed too—crashing, dying, or disappearing, never to be found again.

You’d think this would have given people pause. And in some ways it did. Lots of experts wondered whether flying would ever become a reliable mode of transportation.

But in the face of all these problems, all these dangers, pilots were still willing to go, still willing to race, still willing to make daring flights, pushing the limits of what a plane could do—and risking their lives to do it. It’s hard to imagine people today having the same tenacity. But it’s important that we do—that’s what I learned from my research. It’s critically important for a culture, a country, to tackle the challenges it faces, even in the face of failure. It was only because of the advances we made in aviation in the 1920s and ’30s that we were ready for war in the 1940s, that we could mass produce planes, and fly them around the world, fighting on two fronts. Our problems today are different. But we need to face them—and solve them—with the same persistence.

Of the five pilots covered in your book, which one do you most admire?

Oh, gosh. It’s impossible to answer this question. I adore and admire all of these women. And I hope that, with my book, other people will feel the same way. We’ve been handed a very reductive history about this time—like it was just Amelia Earhart making daring and historic flights, like she was all alone. It wasn’t like that at all. Earhart was essentially part of a small, scrappy squadron. They all did amazing things in the face of almost impossible odds.