My Mother Flew Bombers

In 1939, at the age of 17, Geraldine Hardman found her dream job.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/59/285971c7-817b-4436-b754-21645995410f/geraldinehardman.jpg)

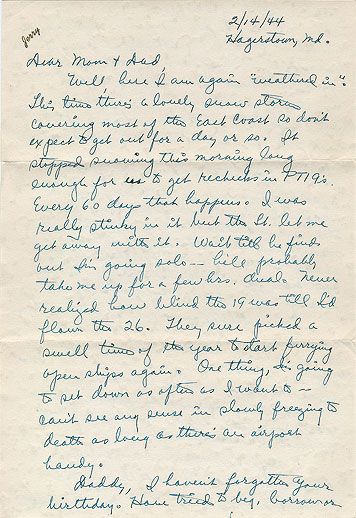

My mother still smiles out at me from a small black-and-white photo on my bookshelf. In the picture, she is a prim young woman in a crisp white shirt and smart pinafore. You can just make out a set of wings—her first—pinned to her chest. It is 1939, and she is only 17 years old. That gleam of silver over her heart and her grand smile say it all: She had achieved her dream. She could fly.

My mother, Geraldine “Jerry” Hardman Jordan, was one of the Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II. She knew she wanted to be a pilot from the time she was five years old, and she could pinpoint the moment she made that decision: May 22, 1927. On that day, she was at her grandparents’ farm outside the tiny town of Ontario, Oregon. The farmhouse had no radio or telephone; when major news broke, a neighbor simply saddled up his horse and rode from farm to farm to spread the word. The news he brought that day: Charles Lindbergh had flown across the Atlantic and landed in France. As my mother would tell us again and again, when the neighbor rode away, she looked up and said, “That’s what I want to do.”

With encouragement from her father and brother, Mom began flying when she was 15. Her uncle, a larger-than-life character named Casey Jones, was a pilot; he ran the small airport in Ontario, and let Mom work at the field. Her first paycheck went to buy a pair of jodhpurs and riding boots, so she could be decked out like her hero, Lindbergh, but after that, every dime of her pay went toward flight time. She did all the airport scut work imaginable: sweeping the enormous hangar, washing airplanes, and—in a demonstration of true dedication—cleaning the inside of Casey’s airplane after he’d taken passengers with fragile stomachs up for their first flights. In return, Casey gave her flying lessons. “I took my time however I could,” she told me. “Fifteen minutes here, 20 minutes there—whatever I could scrounge up the money for.”

Casey had spent some time barnstorming and had a surplus Curtiss Jenny that he used to teach her the basics. “We’d pick out a straight line on the ground, like a road, and fly back and forth making S turns across the road,” my mother explained. “Our favorite entertainment was to fly over the mountains of Idaho and look for landing spots.” On one of these trips, her pocket change hadn’t bought quite enough to fill the tank, and she and Casey had to make an unscheduled landing in a farmer’s field. She told me about chasing away cows, eager to lick the Jenny’s fabric skin, while Casey hiked to the nearest town for gas.

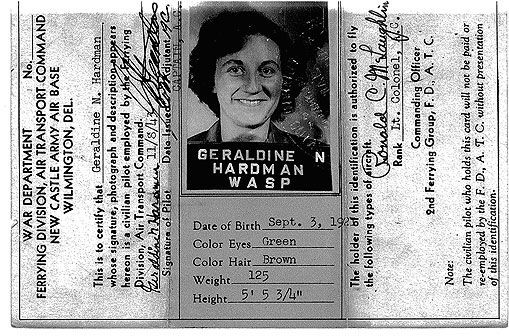

In 1939, the University of Nevada at Reno was granted 20 slots for Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) trainees. Ostensibly established to increase general aviation opportunities, the unspoken message of the CPTP was clear: As conditions deteriorated in Europe, the country needed a pool of well-trained pilots ready to take on military duties. My mother, who had graduated high school early, was working as secretary to the university president. Nineteen young men came forward for the training at the school that year, leaving one slot open, which Mom took. The program provided a 72-hour ground school and 35 to 50 hours of flight instruction. My mother earned her pilot’s license that year, but after war was declared in 1941, pilots had to prove their identity to get a wartime aviator’s ID. She couldn’t produce a birth certificate, and struggled for a year to get authorized to fly. At the same time, efforts were under way in Washington, D.C., to put America’s female pilots to work for the war effort.

Nancy Harkness Love and Jacqueline Cochran had both submitted plans to use female pilots in non-combat missions. Love established the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) with the support of Colonel William H. Tunner, commander of the Army Air Forces Air Transport Command. While Love oversaw the WAFS out of New Castle Army Air Base in Delaware, Cochran set up the 319th Women’s Flying Training Detachment at the Houston Municipal Airport in Texas. By mid-1943, the two groups were merged into the WASP, training at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas. Eventually, 25,000 women would apply for WASP training. Just over 1,800 applicants were accepted; only 1,074 would complete the program.

In assembling the WASP program, Cochran and her staff scoured the records of the Civil Aeronautics Administration to find female aviators to participate. They discovered 2,733 licensed U.S. female pilots in the files, and sent them telegrams inviting them to apply for the WASP program.

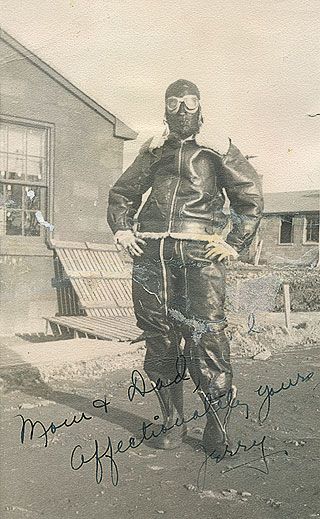

Mom was assigned to Class 43-W-5, the fifth WASP training class and the first group to go through all of its training in Sweetwater. Arriving there, the women discovered the military was ill-prepared to accommodate female aviators. The WASPs were issued men’s surplus mechanics’ overalls—in sizes 44 and up—which the women quickly dubbed “zoot suits.” One of my favorite photos of my mother is her in her baggy zoot suit, soaking wet and grinning like crazy, after going through an Avenger Field ritual: a dunk in the field’s wishing well to celebrate a successful solo flight.

WASPs went through 22 1/2 weeks of training as rigorous as the training male Army Air Forces cadets received, but the women skipped gunnery and formation flying. Simply surviving training could be risky: 11 women died before reaching graduation. My mother told stories of near disaster, such as climbing into airplanes that were sometimes missing pieces of equipment here and there. Once, during a posting to New Castle Army Air Base, she tried to land an AT-6 at night. The whole flight had been beset by mechanical problems, and, on approach, neither my mother nor the tower could tell if the landing gear was down. Mom described flying that Texan in circles over the Atlantic Ocean for more than an hour to burn excess fuel. She was terrified upon landing, but to everyone’s relief, the gear was locked down and all was well.

Although the work carried significant risks, that time in my mother’s life created some of her most treasured memories. When she talked about her WASP days, she always said that she would not have traded the experience for anything. “I just loved it,” she would say. “If I had to pay them for the privilege, I still would have done it.” She talked not just about her love of flying but also about the satisfaction of carrying out a patriotic duty.

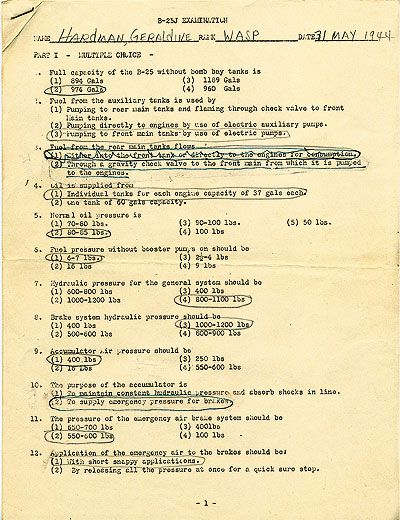

Mom graduated from training at Avenger on September 11, 1943, and was posted to the Air Transport Command at New Castle Army Air Base. During her time in the WASP, she flew Vultee BT-13 trainers, Cessna AT-17 Bobcats, Douglas C-47 transports, and, later—much to her delight—North American B-25 Mitchell bombers. “Most of us would never have gotten near these planes any other way,” my mother once said. “Who would have had enough money to put gas in a B-25?”

On occasion, the women’s challenges were compounded by chauvinism. With great amusement Mom told me a story in which she and several other WASPs delivered aircraft to a coastal base. After approaching the field in tight formation, the pilots executed a series of flawless landings. When the women hit the hangar, the mechanics were laughing. The ground crew explained that a rather blustery Navy officer had watched the WASPs approach and land. He’d declared that because of their precision and skill, the group had to be Navy men. When the women started hopping out of the airplanes, the officer’s face burned red. Embarrassed, he didn’t stay to commend the pilots on their expertise.

But sometimes the bigotry led to sabotage, as my mother wrote in a letter home:

“Yesterday it cleared up enough for me to take off so I tore into my zoot suit, snagged a Red Cross car for my bags & went out to the line—no PT19A—no little silver ship in sight ever—nothing but B26’s and dive bombers! An hour later when it was too late to take off, I finally located my baby in sub-depot minus a prop & with a big hole in the wing which 2 mechanics & the cap’t in charge were frantically covering. I’ve never yet gotten the story but somebody sure did me dirt!”

Thirty-eight WASPs died in service, including several of my mother’s classmates. Paula Loop, one of her dearest friends, died in the crash of a BT-13 near Medford, Oregon, and Mom was dispatched to escort her body home to Oklahoma. As civilians, the WASPs received no benefits and had no right to a military funeral—not even a flag for the coffin.

When Mom’s brother Franklin, a naval aviator, was lost in the Pacific theater late in 1943, she requested a transfer to a western base to be closer to her family. But coming back to New Castle after a ferry mission early in 1944, she discovered the WASP barracks empty; her entire unit had been assigned to another base to fly pursuit aircraft. She had not been sent on to pursuit school because she’d already requested a transfer. For her whole life, my mother regretted the decision. “I opened my mouth when I shouldn’t have. I would have been in fighters otherwise. People make their mistakes. I wish I hadn’t made that one.”

While waiting for her westward transfer to go through in the spring of 1944, Mom was chosen to go to Orlando, Florida to participate in the WASP’s first Officer’s Training Course. Efforts were under way to militarize the program and grant commissions to the women. But male civilian pilots, fearing a loss of their draft-deferred status, lobbied hard against the militarization bill, and opposition grew in Congress. The press railed against the women, calling them “the powder puff brigade” and questioning their value to the war effort. By June 1944, the militarization bill was defeated in Congress, and by October, the remaining WASPs were informed that the program would be shut down in December.

While the training course in Florida kept my mother from the chance to fly fighters, it opened another door for her. Just a few days after arriving in Orlando, she met a young officer on a weekend trip to Daytona Beach. A whirlwind romance led to a June wedding, and in just a few weeks, my mom was expecting her first child. She didn’t want to stop flying, but a side effect of her pregnancy was altered depth perception; she found herself landing airplanes above—and not on—the runway, so she tended to overshoot the landing. “Hard on plane and pilot,” she explained. WASPs had married and gotten pregnant before, but while other women in those circumstances had been granted a leave of absence, Mom wasn’t told that she could take one. With no other alternatives, she resigned from the WASP in August 1944. She was not allowed to write—or even sign—her own resignation letter. In a box of my mother’s papers, I found a copy of that cold form letter, stating that she wanted to quit simply to be with her husband. Years later, her frustration over the resignation boiled over, and in 1979 she wrote a letter to the Air Force noting that she “resented the implication that [she] would quit for a frivolous reason.” The only response she got was a form letter and instructions for applying for her honorable discharge.

On December 20, 1944, the WASP organization was disbanded; the women had to spend their own money to get home. Their groundbreaking, patriotic work swept into the footnotes of history, many of the pilots were embittered. It would take 33 years for the women to be granted veteran status through an act of Congress.

By 1950, my mother had three young children. She had not given up her aviation ambitions, though. She told me that on the day she took the exam for a commercial license, she had no money for a babysitter. The only woman in the room, she took the test with an infant over her shoulder.

Eventually, though, with a rapidly expanding household of rambunctious children and a shoestring budget, my mother realized her aviation career had ended. It was a choice, she said, she was happy to make. She had grown up in difficult circumstances, without the love and attention of her own mother. While flying was her passion, she was willing to pass up time in the cockpit to lavish affection on her kids. I always admired that my mother never seemed bitter about giving up her wings. While she never denied that she missed being in the cockpit, she never resented her kids for grounding her. Rather, she was determined to expose me to as much of her flying world as possible.

As we grew up, our mother’s anecdotes about WASP life became part of our everyday lives. My mother had been indelibly marked by her wartime experience, and stories of flight and the war were as commonplace to us as fairy tales are to other children. But as the last of nine kids, I know I was, in many ways, more fortunate than my older brothers and sisters. My mother was 44 years old when I was born, her hair already salt-and-pepper when I was in grade school. No longer chasing a whole herd of kids, she had more time to tell me her flying stories and share her memories.

My childhood was punctuated with airshows, visits to aviation museums, and WASP reunions. I was named for one of Mom’s classmates, as was my sister Mary. I loved seeing her with her friends, bound by a unique experience. Virtually no one outside our family knew Mom was a pilot, so the reunions raised her spirits.

When I was five, our family moved from New Jersey to Moline, Illinois. While my teenage sisters were less than thrilled to leave the East Coast, for a grounded pilot, Moline was a choice spot to land: small airport, an easy four-hour drive to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and—just an hour down the road—Galesburg, Illinois, home of the National Stearman Fly-In. Together, my mother and I painted compass roses at small rural airstrips and washed airplanes to raise money for the Moline chapter of the Ninety-Nines, a women’s flying group. She taught me about map reading, using a silk map of the China-Burma-India route, given to her by a pilot who’d flown the Hump, the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains. She quizzed me on aircraft silhouettes, and taught me the basics of flying. Now and then, if she got wind of a unique aircraft making a stop at our airport, she’d pull me out of school to see it.

As the years went on, my mother’s body could not keep up with the sharpness of her mind. In 1997, she flew out to join me in Washington, D.C., for the dedication of the Women in Military Service for America memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. Using a wheelchair, and with her vision fading, she found the trip challenging, but she told me she wouldn’t have missed it for the world. That journey was my mother’s last time on an airplane. The female pilot of the flight out of Washington was so thrilled to have a WASP on board, she called for a standing ovation from the passengers and brought my mother up to check out the cockpit. Mom was exhausted, but she wasn’t about to pass up a chance to check out the controls on a jumbo jet.

At the dedication, I watched my mother beaming with quiet pride as astronaut Eileen Collins, who would go on to become the first woman to command a space shuttle mission, addressed the crowd of thousands, singling out the WASPs for their inspiration and for breaking down the barriers against women’s careers in aviation. Dozens of people recognized the distinctive wings on Mom’s jacket and approached her. They came up to shake her hand, thank her for her service, and to take a picture with her. It was a remarkable moment in a life lived largely in the shadows of history.

Melissa Jordan is a writer based in the Washington, D.C. area.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/WWll_Bombers_GALL_1_AUG2010.jpg)