A Female Aviator in 1926 Needed a Stunt. So She Flew Under the Brooklyn Bridge.

Ninety-four years ago this week, Viola Gentry decided to make a name for herself.

:focal(399x225:400x226)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/f4/bef473df-2d69-40ec-86e1-a27e3d586900/viola_gentry_detail.jpg)

You could say Viola Gentry was a rebellious teen. In 1910, when she was just 16 years old, she had already run away to join the circus, gotten married, and divorced. Her parents sent her to live with her aunt and uncle in Jacksonville, Florida, in hopes it would rein her in. It was there, during a chaperoned trip to an ostrich farm, that Gentry found her calling. Amid all the ostrich-related activities and souvenirs, she met pilot George A. Gray, who was offering rides in his airplane. Gentry counted her pennies and climbed in.

For the next eight years, she cobbled together a livelihood working as a hotel receptionist and cashier. By 1920 she had made her way west, and was working at San Francisco’s Grand Hotel. One July morning she learned that stunt pilot Ormer Locklear was shooting scenes for The Skywayman, and would land his airplane on the roof of the St. Francis Hotel. Gentry would write of Locklear’s stunt years later in her self-published memoir, Hangar Flying. “[It] seemed very easy…. If a man could do it, certainly a woman could. All she needed to do was learn to fly.”

Gentry saved enough for a flight lesson, and headed to Crissy Field, where her instructor was Robert Fowler, the first person to fly across the United States from west to east. As Gentry’s biographer Jennifer Bean Bower relates, Fowler was at first dismissive: “A woman should not fly, but should stay home, get married and raise a family.” But Viola persisted, even though each flying lesson cost her the equivalent of three weeks’ wages. (That alone set her apart from other early pilots, says historian Tom Parramore in Bower's book: “She was among the few blue-collar participants in a society of the gilded elite.”)

Gentry felt the East Coast would provide more opportunities for a fledgling female aviator; she moved to New York, and soloed in a Curtiss JN-4 in 1925. The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale granted Gentry an aviator certificate in 1926. Knowing she had to perform a stunt to get noticed, on March 14, 1926 she rented a Curtiss Oriole, took off from Curtiss Field and zipped under both the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. She wasn't the first to do that—Wright Exhibition Team pilot Frank Coffyn had flown under the bridges in 1912—but she was very likely the first woman. Her stunt delighted the press, which immediately dubbed Gentry “the flying cashier.”

Two years later she would set a solo endurance record, the first officially recorded for a female pilot. She was the first federally licensed female pilot from North Carolina, and one of the first nine in the country.

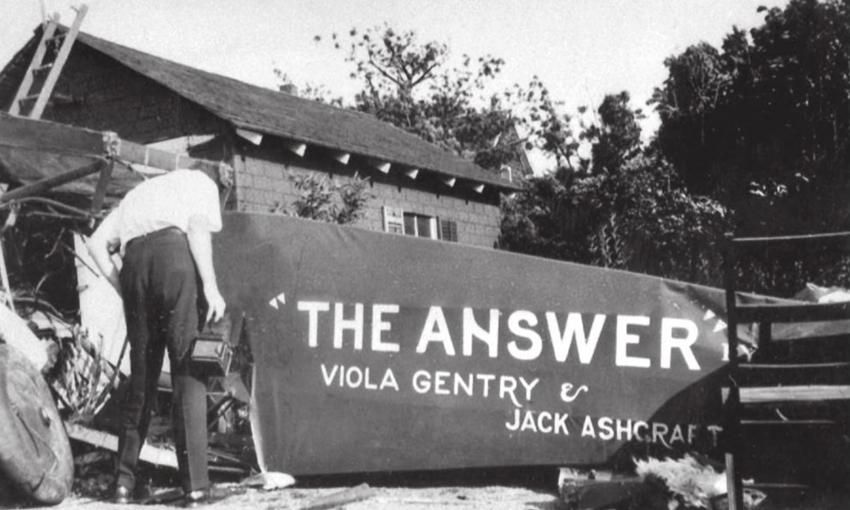

By this time, Gentry was nationally known. In 1929 she was determined to establish a refueling endurance flight record. The time to beat had been set by the crew of the Fort Worth, a Ryan B-1 Brougham that had stayed aloft more than 172 hours. Gentry asked “Big Jack” Ashcraft, another well-known pilot of the day, to help her attempt the record. But tragedy struck. Due to dense fog, the refueling aircraft couldn’t reach the duo’s Cabinaire, and they couldn’t see well enough to land. With Ashcraft at the controls, the airplane ran out of fuel and crashed. Ashcraft was killed instantly; Gentry was severely injured. She would spend the next 18 months in the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled in Manhattan.

After such a devastating crash, another pilot might have given up flying. But as Bower relates in her biography, Gentry eventually returned to aviation, although she always flew with another pilot to compensate for her injuries. In 1960 and 1961 she competed in the All-Woman Transcontinental Air Race with Myrtle “Kay” Thompson Cagle, who would go on to become one of the so-called Mercury 13, the group of women who trained for spaceflight at the same time as the first U.S. astronauts, but never got a chance to launch.

After nearly 50 years as a cashier, Gentry landed her first aviation-related job in 1967, traveling the country on behalf of the University of Texas, urging her fellow Early Bird pilots to donate their records to the university’s History of Aviation archives. She was 73 years old.