The Flying Darkroom

The photographs of Swissair founder Walter Mittelholzer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/11/b1113557-7434-4c93-b481-9d9b33b8f2c9/mittelholzer_flash_image.jpg)

It was ingenious, really. In the 1920s, when Walter Mittelholzer prepared his Dornier-Merkur (named the Switzerland) for aerial photography work, he had the inspired idea to remodel the bathroom into a darkroom. As historian Kaspar Surber notes in the recent book Walter Mittelholzer Revisited, the darkroom allowed Mittelholzer to do some trial developing while still in the air. Mittelholzer frequently flew with a mechanic who would act as pilot when Mittelholzer handled the cameras or popped into the darkroom, says Michael Gasser, head archivist at the ETH Library in Zurich, which holds the extensive Swissair collection. “The idea was to check which exposure time was ideal for the current setting—desert, rainforest—to make sure that the photographs taken during a flight would turn out all right,” says Gasser.

Mittelholzer took his first aerial photographs during World War I while working towards his pilot’s license. In 1919, he and his flight instructor Alfred Comte formed an aerial photography company with the mind-bending name of Aero-Gesellschaft Comte, Mittelholzer und Co., Luftbildverlagsanstalt und Passagierflüge. This entity, in 1931, would morph into Swissair. “With small airplanes and seaplanes, they flew rich and adventurous tourists from Zurich to the Alps; and business people to German, Austrian, and Swiss cities,” writes Ruedi Weidmann in Swissair Souvenirs: The Swissair Photo Archive. “However, at first, the commercial pillar of success came from aerial photography: the sale of prints to photographed factories, hotels, and communities.”

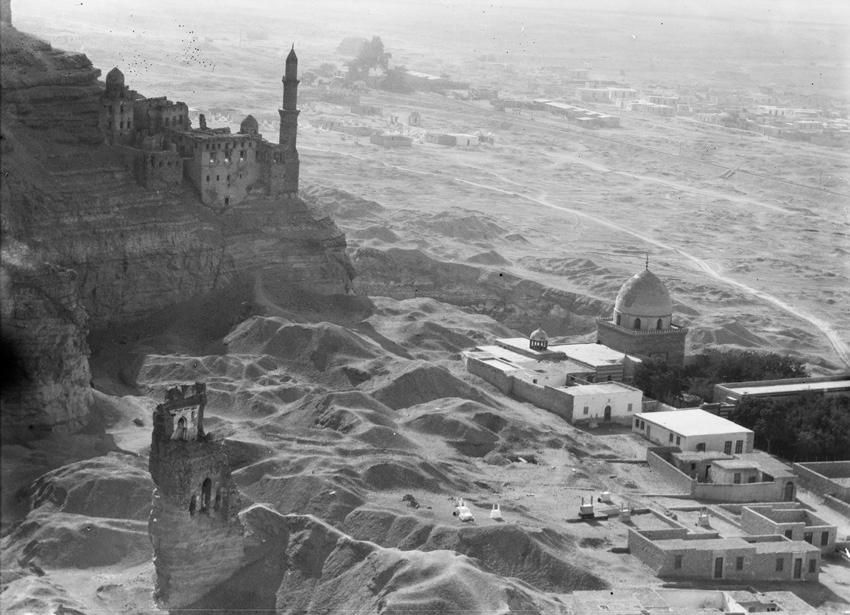

In 1926, Mittelholzer made the first north-south flight across the African continent and was the first person to fly over Tanzania’s Mt. Kilimanjaro, in 1929. Historians have described Mittelholzer as an aviator first, and photographer second. But the opposite is closer to the truth, says Suber. “Mittelholzer was a media entrepreneur, whose most important tool was the airplane.” Mittelholzer’s images of African and Middle Eastern landscapes would make him a household name; his travel books were bestsellers and he was a master at courting sponsors to underwrite his trips. The food and beverage company Nestlé, notes Suber, “brought out a board game with which children could follow Mittelholzer’s progress through Africa.” But not all of his trips were financed in this way. Mittelholzer’s flight over Kilimanjaro was bankrolled by a hunting safari commissioned by Baron Louis von Rothschild, while a 1934 delivery of a Swissair aircraft to Abyssinian Emperor Haile Selassie led to rare access to the royal family and palace. Abyssinia reminded him of Switzerland: “Its highlands, which like some monstrous fortress to the south and east are encircled by an all but impenetrable desert, have earned it the moniker ‘Africa’s Switzerland’,” he would later write.

Suber isn’t afraid to ask tough questions about the legacy of Swissair’s photography: “What was the purpose, and the commercial value, of these photos for the emergence of a Swiss national carrier and for the development of civil aviation in general?” The answer is complex: Neighboring Germany had lost its colonies after World War I, writes Suber, and was officially barred from engaging in aircraft production. “But this simply made German entrepreneurs all the more determined not to fall behind in aeronautical engineering, which in turn explains their eagerness to establish contacts in the one neighboring country that did not have any colonies of its own,” he writes. When Mittelholzer’s company ran into financial trouble in the 1920s, Junkerswerek bought a 50 percent stake in the company. And, of course, German aircraft manufacturer Dornier had built Mittelholzer’s aircraft Switzerland in which he toured the world. And the aviator caught the eye of the Third Reich: “When Mittelholzer’s floatplane landed in Cape Town,” writes Suber, “the German Reich’s Ministry of Transport sent a telegram of congratulations, praising him ‘for this oustanding feat’ and for delivering proof of the ‘reliability of German aircraft and engine design.’ ”

After Mittelholzer died in a climbing accident in 1937, the company resumed aerial photography; after World War II, it continued to sell postcards and photo books. But, as Weidmann notes, the company “also systematically photographed the development of Switzerland’s countryside and cities. [Aerial] photographs were useful in the production of precise maps for the building of highways, hydroelectric power plants, and other major structures.”

The Mittelholzer photographs came to the ETH Library between 2009 and 2012; archival processing took four years to complete. Most of the photos in the collection—now in the public domain—can be downloaded directly from the library’s database. Many of the images in Walter Mittelholzer Revisited are previously unpublished; the beauty of the photographs combined with Kaspar Surber’s scholarship bring new light to the complex genius of Walter Mittelholzer.