The Flying Farmhand

This agricultural drone requires no human supervision at all.

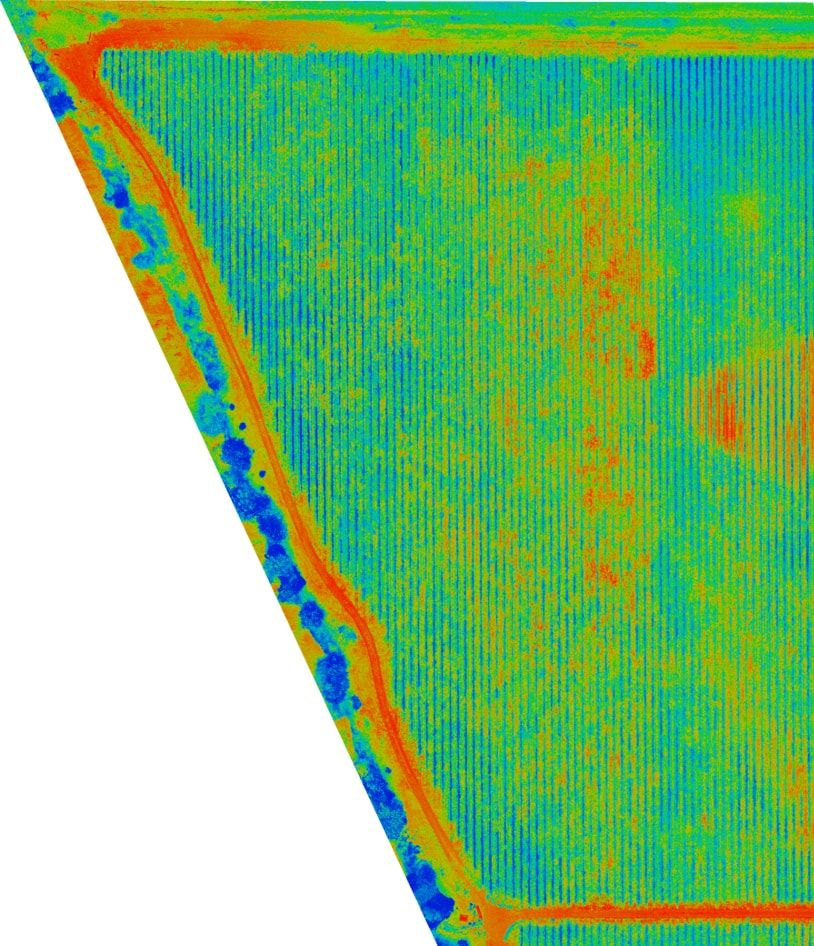

A metal box about the size of a washing machine sits on the ground at a vineyard, when suddenly its top panel splits open and slides sideways. Riding a lift inside the box, a large quadcopter slowly emerges. Within moments, the drone is flying a grid pattern over the grapes, snapping hundreds of photographs with a multispectral camera. When the mission is completed the quadcopter returns to its “hangar,” where it recharges its batteries and uploads the images to a website, where they are combined to create a detailed, nuanced map of the vineyard. This modest-looking little hangar and the drone it houses are the clearest signs yet that agriculture is on the verge of technological shift, with other industries not far behind.

Agricultural drones could have a huge impact on farming by drastically cutting the price of crop imaging, which can be critical to farmers hoping to spot or diagnose problems before they become irreversible. What makes this vineyard flight unusual is that there was no human involved at all. Every aspect of the flight—evaluating flying conditions, lifting off and flying over the field, landing, recharging the battery, and uploading the imagery—happened autonomously. By letting the drone figure out everything on its own, American Robotics has taken crop monitoring to a new level. The result is Scout, a quadcopter-based autonomous flight system currently in beta testing, with initial real-world tests anticipated in 2019.

Scout is truly an “unpiloted aerial system” (UAS) that includes not just the drone, but the systems that help control and navigate it, including a dedicated hangar to provide shelter and power for the aircraft. After an initial setup (during which the farmer defines the vehicle’s flight boundaries and schedules), it can be left alone, with humans looking at results on the computer as often or as little as they please. The whole shebang is small enough to be moved with relative ease, and can launch on slopes of up to 10 degrees, meaning that little site preparation is required. The main requirement for setup is simply hooking it up to a power source. “The primary mode of getting power would be your standard outlet,” says Reese Mozer, CEO and cofounder of American Robotics, “but we’re designing the system to integrate solar panels, a gas generator, or any other standard source of power.”

The hangar comes equipped with hardwired ethernet, satellite, and cellphone signal receivers to obtain the latest operational data, including weather forecasts. Scout “won’t fly in weather too inclement, whether it is too cold, too hot, too windy, too [rainy],” says Mozer. The system “is intelligent enough to utilize weather services—both local and general network weather services—to make a [go, no-go flight] determination” completely on its own. And if the forecast is off, “that is not an issue,” he says. Scout “will be able to handle that and return to base safely and store itself until the weather passes.”

With onboard diagnostics to monitor the aircraft and associated systems, “this thing is not gonna fly” if it has a problem, Mozer says. When a serious failure is detected, the hangar will automatically alert both the system owner and whoever provides routine maintenance.

“This is really designed to work autonomously,” says Mozer. “It is all of these boring supporting tasks that really make operating a drone a time-consuming and expensive operation.” A statement on the company website reads: “No piloting. Ever.”

As autonomy and artificial intelligence improve, consumer-level drones are taking advantage. One so-called “selfie drone” uses image and gesture recognition to follow its owner around, but that person still needs to power up the vehicle, command it to fly, and tell it (through gestures) where to go. An AI-powered drone recently lost to a human in a drone race, but the circumstances were experimental and highly controlled. Scout, on the other hand, is the first of what is likely to be the next great tech wave: systems capable of making so many decisions on their own that people need to provide very little, if any, supervision.

Unfortunately, that means Scout is slightly ahead of its time, and the biggest hurdle it faces today is government regulation. The Federal Aviation Administration’s Part 107 rules, which govern drone flight, restrict UAS to line-of-sight operations, meaning that whoever’s flying it must actually see the drone at all times—an inconvenient requirement for a system specifically designed to work without supervision.

Mozer concedes that the FAA legally prohibits Scout from working autonomously, at least for now, but says he is “confident that the system will function as advertised within the legal framework of the US within the next year.” Any regulatory changes that allow unsupervised autonomous flight will represent a sea change for the UAS industry and herald the arrival of the Holy Grail of drone flight: fully permitted Beyond Line of Sight (BLOS) flying. That privilege is rarely granted today, and still requires a human in the loop should something go wrong. With true BLOS and truly unpiloted aerial systems, huge segments of the economy would be affected: Imagine a package delivery drone driven to its launch location by a self-driving package van, which was itself packed autonomously by warehouse robots. The only human involvement would be the customer deciding what they want. If that day comes, Scout will have helped make it happen.