Fork-tailed Devils and Flying Shoes

What does the Northrop P-61 have in common with Burt Rutan’s SpaceShipOne?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/shoes-388-jan05.jpg)

They look odd. Even though aircraft with twin tail booms have appeared in every era of aviation history—from the early designs of the Farman and Voisin brothers to Adam Aircraft’s turbofan twin awaiting FAA certification—each one looks like a fix to something broken, an escape route from a corner into which a designer has painted himself.

Why do it? Why shorten and interrupt the fuselage and connect the wings to the tail assembly with two tubes? There are as many reasons as there are twin-boom designs. Booms have been used to shave weight, stiffen structure, give fighter pilots better aim, improve the efficiency of propulsion systems, reduce parasitic drag, and expedite the loading of munitions or cargo—sometimes all on the same airframe. Examining the various rationales for the configuration is a good way to understand just how many trade-offs aeronautical engineers have to make to build an airplane that will not only get off the ground but do something useful after it does. As this collection shows, twin-boom aircraft have been useful at almost everything the more familiar single-tail-boom airplanes do. The ones shown are merely a sample of hundreds of designs. (For more twin tail-boom airplanes and photos of aircraft mentioned but not pictured here, visit www.airspacemag.com.)

Twin-boom designs are still making history. Burt Rutan’s SpaceShipOne, the first private craft to take an astronaut into space, and its dashing launch platform White Knight both have twin tail booms. And if the movies are any guide, the configuration will be flying long into the future: In Ridley Scott’s 1979 science fiction classic Alien, the vehicle transporting man’s greatest threat is a giant spacecraft with twin booms.

SON OF A HOMEBUILT

The North American OV-10 Bronco owes its successes during the Vietnam War to the tenacity of two Marine Corps majors, K.P. Rice and Bill “Flameout” Bennett. In 1961 no one was interested in a small, short-takeoff-and-landing aircraft designed to support troops who were fighting guerrillas. But Rice and Bennett knew what was needed and built it in Rice’s garage. It was going to “dive bomb like a Stuka or an SBD, maneuver like an SNJ/AT-6, and be as fast and strong as a Corsair,” Rice remembers saying to anyone who’d listen. Obsessed with installing a 106-mm automatic recoilless rifle on the centerline, they added twin booms to lift the empennage out of the back blast. The Lockheed P-38, Rice says, had already demonstrated that placing guns on the centerline increases the shooter’s accuracy. Why the 106 rifle? “We were going to hit targets,” Rice says, “not surround them with bombs.” Twin booms also enhanced survivability, because redundant control systems were in the booms, widely separated. The military services came around to the need for a counter-insurgency aircraft, but in designing one, they increased its size, weight, and variety of missions—and dropped the 106. Still, the Bronco in its final form was a potent warplane. Kit Lavell, a pilot with a Navy OV-10 squadron known as the Black Ponies, says proof of the aircraft’s effectiveness in supporting SEALs and riverine forces was that “the enemy prepared crude handbills with the shape of the plane depicted on them and prescribed tactics to shoot down the Bronco.

CENTERLINE THRUST

Adam Aircraft expects the Federal Aviation Administration to certify its new push-pull, twin-boom business aircraft, the twin-engine A500, within the next few months. It’s a new airplane but an old idea. The concept of centerline thrust took shape most recently in the Cessna 336.

When it debuted in 1964, the 336 crowned years of development toward a simple, low-cost aircraft offering the safety of two engines without the conventional twin’s tendency to yaw if one engine fails. Twin tail booms made room for the second engine at the rear of the fuselage, and the two engines provided centerline thrust and a comfortable ride. A year later Cessna brought out the 337 Skymaster, which had more powerful engines and retractable landing gear. It was a controversial airplane. Despite the safety-oriented sales pitch, the Skymaster’s accident rate was higher than that of conventional twins. Hangar wags referred to it not as the Skymaster but the Mixmaster. But in 1966 the Air Force liked the 337’s high-wing visibility and ability to use short, rough fields, and it bought the twin as a forward air control craft. More than 500 of the 337s were fitted with rocket pods and smoke generators and shipped to Southeast Asia as Air Force O-2s. Author and O-2 pilot Robert Mikesh says the O-2 “felt civilian” and recalls “one ham-handed guy literally pulling the door handle off,” but gives it “a 9 on a scale of 10” for mission suitability.

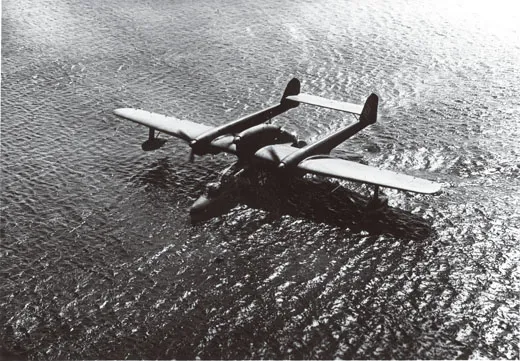

TWIN BOOMS WITH SEA LEGS

Making headlines around the world—and earning propaganda dividends for Italy’s Fascist government—for a series of transatlantic flights in the 1920s and ’30s, the unique Savoia-Marchetti S.55 flying boat had two engines, two hulls, two tail fins (and three rudders), and of course two booms. The cockpit fit into the center section of a thick wing supporting engines with pusher and tractor props mounted in tandem on centerline pylons. Designed as a torpedo bomber and minelayer but seeing no action in World War II, the S.55 is best remembered for a July 1933 stunt when 24 of them flew from Rome to Chicago. Led by Italy’s flamboyant young air force general, Italo Balbo, the formation arrived for the World’s Fair in a little over 48 hours. (According to National Air and Space Museum archivist Brian Nicklas, the performance so impressed the world that for years any large formation of aircraft was referred to as “a Balbo of airplanes.”)

In the following decade, a twin-boom amphibian, the single-hull, tri-motor Blohm und Voss Bv 138, nicknamed the Flying Shoe, attacked Allied ships in the north Atlantic and distinguished itself by engaging in a dogfight with a Consolidated Catalina flying boat—and winning. Bv 138s menaced Allied convoys, but by late 1942 they were being quickly rendered obsolete by the deployment of Allied aircraft carriers and their fighters. On May 1, 1945, one of the few remaining Shoes alighted under fire on a Berlin lake. Its mission was to pick up and deliver two envelopes, but the pilot ignored the order and instead picked up 10 wounded and delivered them to Copenhagen, Denmark. In those envelopes, it was later found, was Adolph Hitler’s last will and testament.

A BUNCH OF GHOULS

When the de Havilland D.H.100 Vampire was designed in 1942, the turbojet was an immature technology. The jet pipe had to be kept short to limit loss of thrust from the anemic Goblin engine. So the engine was installed behind a short, molded-plywood cockpit. Shaving weight, skinny twin booms were employed to lift the tail assembly clear of the exhaust. Empty, the airplane weighed a mere 6,372 pounds.

The Vampire appeared too late to joust with the Me 262, but in 1945 it became the first fighter to exceed 500 mph and the first jet to land on an aircraft carrier.

In 1951, de Havilland debuted the D.H.112 Venom, evolved from the Vampire with a Ghost engine (again the ghoulish theme), which was 40 percent more powerful than the Goblin. By 1960, when this Addams family of twin-boom jets culminated with the all-weather, swept-wing D.H.110 Mk. 2 Sea Vixen, the booms were called on to do more than support the tail assembly. Packed with tanks, they were extended forward of the wings to carry more fuel for the two 10,000-pound-thrust Rolls-Royce engines.

LOCKHEED’S LEGEND

Called “the fork-tailed devil” by the Germans, the Lockheed P-38 Lightning was also called “funny-looking” by the U.S. Army when its representatives saw the design in early 1937. Lockheed designer Kelly Johnson famously wrote in his autobiography that by the time the Lockheed team had stuffed the long Allison inline engines into nacelles with turbo-superchargers and landing gear, “we were almost back to where the tail should be. So, we faired it back another five feet….” Johnson needed two 1,150-horsepower Allison V-1710 engines to achieve the required speed of 360 mph (the operational fighter bested 400) and climb rate of 20,000 feet in six minutes. The design enabled him to cram in all that propulsion with the smallest drag penalty. The centerline cockpit nacelle allowed for good visibility and carried four machine guns and a cannon—a devastating stream of forward fire without the complication and weight penalty of an interrupter gear to keep the guns from shooting a propeller blade.

Although the P-38 is the most famous twin-boom combat aircraft of World War II, it is not the first. That distinction belongs to the Fokker G.1, which first flew in 1937, two years before the XP-38.

A distinguishing feature of the other U.S. twin-boom fighter to enter service during the war, Northrop’s P-61 Black Widow, was the big radar in its nose, which enabled it to fly missions at night. It carried up to three crewmen in the central fuselage, four belly-mounted 20-mm cannon firing forward and, in some models, a powered, remote-controlled turret equipped with four .50-caliber machine guns. Gerald H. Balzer, a former Northrop engineer, says the design team worked from a sketch made in 1940 by the Air Technical Service Command at Wright Field in Ohio. His thoughts on the twin-boom arrangement: “The configuration of an airplane depends on what you want to cram into it.”

LOCKHEED’S LEGEND

Giulio Douhet and Gianni Caproni could be considered the twin pillars of Italian air power in World War I. Because of their collaboration, says historian John H. Morrow Jr. of the University of Georgia, “Italy put up a very strong aerial effort in relationship to its economic resources.”

Morrow adds: “Douhet believed that you could knock another country out of the war by bombing strategic targets—hydroelectric plants, railway stations and junctions, ammunition stockpiles, and factories. And Caproni was willing to design large aircraft to do just that.”

With a wingspan of 73 feet, Caproni’s Ca.3 biplane bomber was one of the largest aircraft fielded in World War I, almost 20 feet wider in span than the war’s other twin-boom biplane bomber, France’s Caudron G.4. (It was a big-airplane war: Handley Page built a four-engine giant with a 120-foot wingspan.)

Like so many of its contemporaries, the Caproni bomber used a combination of pusher and tractor propellers; Caproni placed the pusher at the rear of a short, bathtub-like fuselage, the only ungraceful feature of a beautifully proportioned airplane. Its most famous missions were low-level night raids, flown in 1917 across the Adriatic Sea, to surprise the Austro-Hungarian fleet while it was at anchor in Pola (today Pula), Croatia.

The year before, a second gunner’s position was added above the rear engine. “It must have been a ferociously difficult position,” says Morrow, the author of The Great War in the Air (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993). “It was located up and in the slipstream and the weather. Many of those crews won Italy’s highest honor for bravery in combat. I marvel at what men did in World War I.”

A MACHINE FOR SEEING

What must the view have been like from the Abrams Explorer? The two-place crew nacelle, pushed so far forward that not even the wings encroached on the scenery, was glazed top and sides with plexiglass, like the nose of a World War II bomber. Flying by November 1937, the Explorer was one of the first U.S. aircraft with a twin-boom configuration, used so that the radial pusher engine could be mounted aft, where it wouldn’t block the view. It is one of only a few aircraft of any configuration designed solely for surveying and mapping. Early on, the Army was interested in Talbert Abrams’ camera platform, but decided instead to convert fighters for combat photo reconnaissance. Civilian markets didn’t materialize. Undaunted, the former Marine pilot went on to start the ABC Airline (“Always Be Careful”) and was famous throughout hometown Lansing, Michigan, for his airplane-shaped house. Today, his Explorer is awaiting further restoration at the National Air and Space Museum.

At virtually the same moment Abrams was creating the Explorer, across the Atlantic another twin-boom aircraft was being designed and built for maximum visibility, but the client had no interest in surveying. Conceived in February 1937 and flying by July 1938, the Luftwaffe’s Focke-Wulf 189 Uhu (Owl), known as Das Fliegende Auge (the Flying Eye), had small, air-cooled engines and retractable gear in the booms and a generously glazed central nacelle on top of the wing. Though armed with six machine guns, two cannon, and, at times, spray canisters of mustard gas, most 189s flew short-range reconnaissance missions on the Eastern Front. One was a personal transport for Albert Kesselring, a supreme commander of German air and ground forces.

GOING GLOBAL

To make the first nonstop, unrefueled flight around the world, Burt Rutan designed a flying fuel tank. “The Voyager booms hold a large percentage of the fuel,” Rutan says, “and [the fuel] had to be mounted along the span to keep the wing spar from being too heavy.” Two tanks in each boom, four in each aft wing, one in each canard, and three in the fuselage held 7,000 pounds of fuel, or 72 percent of the craft’s gross takeoff weight.

The long, thin wing was not stiff enough to support the booms. Rutan’s solution was to stiffen the structure by connecting the forward tips of the booms to a canard wing to hold them in position and keep them from twisting the main wing. To conserve fuel, the aircraft was to be powered most of the trip by one engine (the pusher), so Rutan mounted both engines on the centerline. After its nine-day flight in December 1986, Voyager landed with just 106 pounds of fuel, or about 16 gallons—enough for a little over three hours’ flying.

Twin booms are becoming almost as much a hallmark of Rutan’s designs as the ever-present canards. He also uses the configuration on the Global Flyer, in which record holder Steve Fossett intends to attempt another solo around-the-world flight before April 2005.

U-2SKI

Vladimir Mikhailovich Myasishchev initially created the M-17 Stratosphera (that’s “Mystic,” to NATO) to shoot down U.S. reconnaissance balloons. By the time of its 1982 first flight—after its designer’s death—it had lost its gun turret and become a spyplane. The design was probably influenced by two earlier projects: the twin-boom Sukhoi Su-12, a 1947 piston-engine recce aircraft that went only as far as prototype, and the Yakovlev Yak-25RV, a high-altitude reconnaissance jet with sailplane-like wings similar to those of the M-17. The Mystic could loiter for four hours at 65,000 feet, but it never achieved the altitude performance of the Lockheed U-2, its U.S. counterpart. Its short fuselage is the single design advantage the M-17 had over the U-2. Says aviation historian Jay Miller, “Jet engines—regardless of whether they are turbojet or turbofan—lose efficiency depending on the length of the exhaust pipe. The U-2’s fuselage and associated lengthy engine exhaust tube have historically been one of its few Achilles’ heels.” A twin-engine descendant, the M-55 Geophysika, flies atmospheric research missions, just as NASA’s ER-2 research craft—civilian versions of the U-2—do in this country.

GUNBUS

In aviation’s baby days, twin tail booms were an answer to the question “Where do we put the propeller?” Before Anthony Fokker’s 1915 invention of a mechanism to synchronize the firing of a machine gun with the spinning of propeller blades (the gear first appeared on the Fokker E.1 Eindecker fighter), placing the engine and propeller behind the fuselage cleared the way for a gun in the nose. The U.S. Army banned pusher engines in 1914 after several pilots died in crashes, but many European World War I aircraft used them. The first British airplane designed as a fighter, the Vickers Fighting Biplane 5, also known as the “Gunbus,” had a pusher, as did the Airco D.H.2. Both fighters used a fixed forward gun—and were frequently shot down from the rear.

FENCED IN

Former Secretary of the Navy John Lehman became a believer in unmanned aerial vehicles in 1983. After the bombing of a U.S. Marine Corps barracks in Beirut, Lehman viewed a video shot by an Israeli UAV. It showed the Marine commandant inspecting damage. The aircraft had been so inconspicuous that the general had no idea he was on camera, yet Lehman easily recognized the man. The U.S. Navy’s RQ-2A Pioneer UAV was born.

Like the Israeli Scout, from which it evolved, the 450-pound Pioneer has 40 pounds of sensors and cameras up front, balanced by a two-cylinder, 26-hp gasoline engine and pusher propeller behind. Steve Reid, program manager for Pioneer UAV Inc., says the booms, besides supporting the tailplane, have served as a fence around the propeller, preventing injuries in the tight shipboard and battlefield environments where the Pioneer operates.

OPEN WIDE

The U.S. Army Air Forces needed a dedicated military cargo plane so desperately in 1942 that General H.H. “Hap” Arnold ordered development of the Fairchild C-82 Packet after seeing only a rough sketch. Twin tail booms, a high wing, and a low-hung fuselage allowed most wheeled vehicles to drive right into the cargo bay. It had enough room for 44 paratroopers or 2,870 cubic feet of cargo—the size of a standard railroad boxcar, hence its nickname, the Flying Boxcar. Packets, however, played no role in the war. By 1948 the C-82 needed a host of modifications (though not the hatchet job performed by Jimmy Stewart and castmates in the 1965 movie The Flight of the Phoenix). The result, the C-119, now officially the Flying Boxcar, carried more cargo and paratroopers farther and faster. It served in the Korean War, playing a critical role in the Chosin Reservoir breakout in December 1950 by dropping eight bridge sections that created an escape route across a deep gorge (see “Breakout from Chosin,” June/July 2000). In Vietnam, AC-119G Shadow and AC-119K Stinger gunships supported ground combat with flares, infrared sensors, and four Gatling miniguns. The Stinger also had two 20-mm Vulcan cannon. Hawkins and Powers Aviation of Turnbull, Wyoming, still flies a C-82 and two C-119Gs (one was just used in a remake of The Flight of the Phoenix).

A final version, the XC-120 Packplane prototype, featured a detachable container pod, which mated to the fuselage by means of complicated gear that tucked into the fuselage and booms in flight. World War II Army Airborne legend General James M. Gavin called it “the most significant development ever produced by the American aircraft industry.” None were ordered.