Freeing Spirit

NASA’s Mars rover prepares to escape the worst trouble of its life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Spirit-Moves-hero.jpg)

For all their skill and experience navigating the Martian landscape from millions of miles away, the people who drive the Spirit and Opportunity rovers didn’t see this one coming.

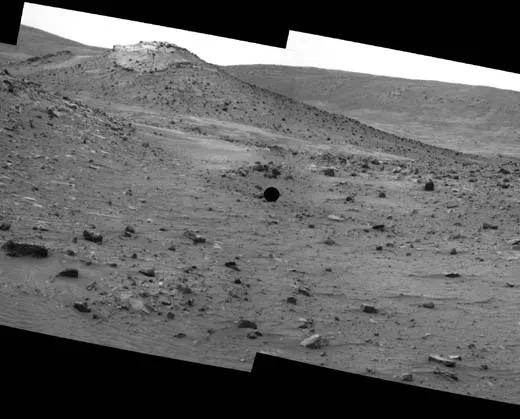

Last April, as Spirit was heading south near a rock formation known as Home Plate, the six-wheeled robot rolled into a “camouflaged tiger trap,” as project manager John Callas puts it. What looked to the drivers like solid ground turned out to be a shallow crater filled with powdery sand, with a thin crust on top. The rover’s wheels broke through the crust and sank into the powder, and initial attempts to roll out just dug the wheels in deeper.

Spirit has been stuck ever since. Now, after seven months of studying the problem and rehearsing with full-scale mockups of the rover in a “sandbox” at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, the drivers are ready to start what they call “extrication”—perhaps as early as next week. This is the worst jam either rover has gotten into since landing on Mars in January 2004, and success is not guaranteed. “We know we’re in a pickle,” says John Grant, a planetary scientist with the National Air and Space Museum who pulls regular duty chairing the team that plans the rovers’ daily scientific observations. But, he says, “I’m very hopeful.”

The plan is to have Spirit drive out the way it came in, which means heading slightly uphill and to its right, using a “crabwalk” motion with the wheels turned at an angle. This time, the rover will be facing forward. (Spirit rolled backward into the crater in April—it’s been driving that way since 2006, when a problem with its right front wheel left it hobbling like a broken grocery cart, and easier to control in reverse.)

The rover only has to move a meter or two to get free, but Callas expects the extrication will take months. The drivers will command the rover to turn its wheels, wait a day while they analyze the results, then press ahead if they see the situation improving. Progress will be measured in centimeters.

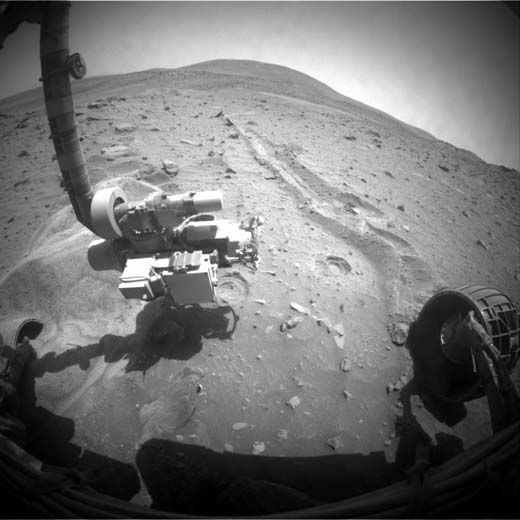

At the moment, both rear wheels and the left front wheel are deeply buried in powder, and the middle wheels are partly buried. Only the gimpy right front wheel is on solid ground. Also, there’s a big rock stuck under the rover’s mid-section. The operators at JPL have used an arm-mounted camera to take pictures of the rock, but this particular camera—the microscopic imager—is normally used for extreme close-ups, and the pictures are blurry. It’s hard to tell if the rock is actually touching the rover’s belly, or whether it’s loose or embedded firmly in the ground. The last thing the drivers want is for the undercarriage of the rover to get hung up on the triangular-shaped rock.

One other worry: Lately Spirit has been suffering hiccups with its flash memory, which stores both engineering and science data. As with an MP3 player or camera, the memory only has so many rewrite cycles before it starts to wear out—typically around 10,000, which is close to the current count. The JPL operators are trying to reformat the flash memory to solve this problem before pressing ahead with extrication.

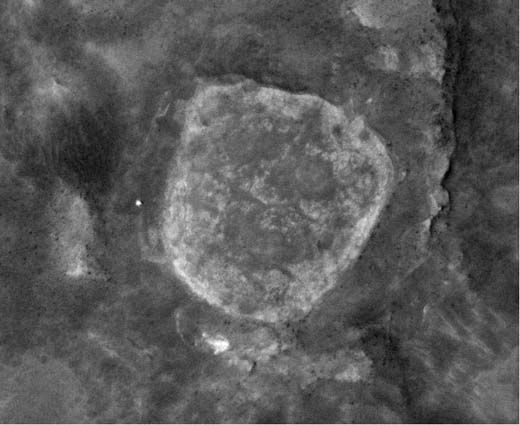

What if it doesn’t work, and Spirit spends the rest of its life parked in one spot? “If you had to get stuck somewhere, this is a pretty interesting place,” says Grant. Based on the geology around Home Plate, and the mineralogy and chemistry Spirit’s instruments have found—particularly the presence of silica—this location is thought to be the site of ancient hydrothermal activity. Here, heat and water would have combined to create a favorable environment for life, if it ever existed on Mars. Grant and his fellow scientists hope to explore a nearby mound called Von Braun and a crater called Goddard, which is where Spirit was headed when it got trapped. Goddard may be the remnant of a volcanic structure, and may be connected to the silica found near Home Plate.

Grant still thinks Spirit will get there. But if it doesn’t, the scientists will undoubtedly make whatever observations they can, for as long as they can, even if the rover never moves again. Callas figures the rover can make it through one more winter before it will need to reorient its solar panels and recharge its batteries.

In dollar terms, Spirit and Opportunity cost just under $1 billion to design, build, launch, and operate for six years. But as the only working robots on Mars, their actual worth goes far beyond that. In fact, they may be the most valuable machines in the solar system right now—which is why the JPL operators, when they finally start to free the rover, will take their time.