Clifford Turpin, King of the Air

He was one of the great original airshow pilots. Why did he hide his past?

:focal(1340x689:1341x690)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/52/3652351b-e120-4c0b-b8ce-86d9dba1de31/09m_on2015_mg_1244_live.jpg)

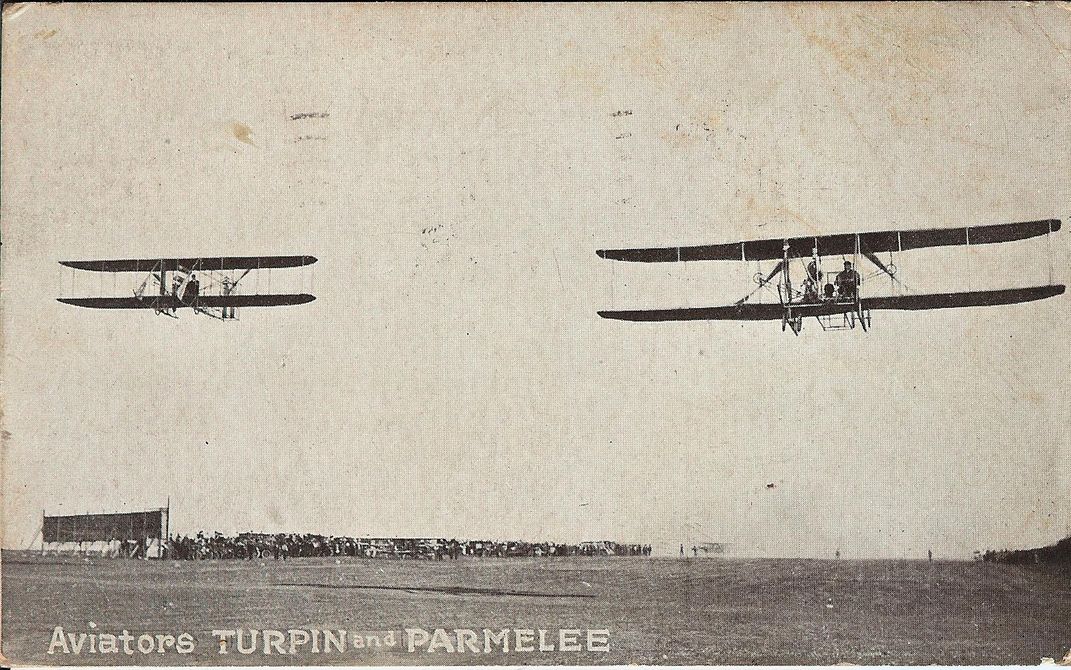

At the Kentucky State FairGrounds in November 1911, the purple handbill promised armored cars, motorcycles, artillery, an ambulance corps, a re-enactment of Mexican guerrillas battling U.S. Army infantry, and most important, the “Wright’s Aviators—Kings Of The Air.” The copy was breathless: “Aviator P.O. Parmelee who did scout duty for U.S. Government on the Mexican border during the revolution, and Aviator Clifford Turpin, the world’s two greatest Aviators fight a desperate duel in the skies.”

Parmelee and Turpin were not only best friends, they were something very rare for the time: veteran airshow pilots. Were they the world’s greatest? Did it matter? The fact that they were pilots was enough, or so the organizers hoped.

Despite a spectacle of impressive-looking troops and sombrero-clad “Mexicans,” the press at the fair reported lousy weather and small crowds. But there were rave reviews of the flying, which included a “pistol duel” and all the standard Wright team dips, spirals, and glides.

Cliff Turpin and Phil Parmelee were absolutely world famous, at least according to the promoters in Kentucky. Earlier that year, the state fair organizers in Illinois (and three other states) said they were world famous too. Turpin and Parmelee themselves said the same thing the next year to the passengers in Venice Beach they sold rides to, and at dozens of other jobs. They were on an adventure that would make a fine epic poem, and they invented the airshow business that, to this day, reflects their influence. Turpin made it out alive; Parmelee didn’t. It ended so badly that for the next five decades, Turpin almost never spoke about his flying days.

Cliff Turpin’s adventure began in 1910. Two years earlier, in 1908, as he graduated with an engineering degree from Purdue University, his fellow Daytonians Orville and Wilbur Wright unveiled the airplane to the world. The Wrights’ demonstrations were revolutionary and their flights triumphant, but beyond contests and air meet entertainment, the airplanes didn’t yet have many profitable applications. Glenn Curtiss, the Wrights’ American arch-rival, grabbed the spotlight in August 1909, when he won the first Gordon Bennett Aviation Trophy in Reims, France. The Wrights, who did not compete in the race but were not to be outdone, began to prepare for the following year’s race, developing what they hoped would be the fastest airplane ever built.

While city-to-city races and distance and altitude competitions certainly spurred advances in flight technology, they also served audiences, which were huge and growing. The public gobbled up flying stories in newspapers, magazines, newsreels, and songs. Anything in the air was entertaining, especially with the ever-present possibility of a good crash.

This is the world Cliff Turpin chose. Dayton, in the first decade of the 20th century, was a powerhouse of innovation—the perfect place for the freshly graduated engineer. Turpin had grown up in his family’s gasoline engine business. His father, James, developed the New Era Gas Engine Company in 1904 out of an already successful iron works. By the time Turpin graduated, his father had spun off a second company, New Era Auto-Cycle. Turpin became the lead salesman. Motorcycle Illustrated magazine reported that at the Boston Motorcycle Show of 1909, “Turpin convinced his visitors that, though a youngster in the business, he knew the New Era from handlebar to rear tire.”

But aviation’s momentum was irresistible. Turpin had already met the Wrights; he’d stopped by their bicycle shop during the time they were inventing the airplane, and he and his father assisted Orville in the development of their engines. In June 1909, Dayton threw a city-wide celebration for the Wrights; in July, the brothers demonstrated the first military airplane. Louis Blériot flew across the English Channel the same month. In August, Curtiss won the first Gordon Bennett race, and in September Wilbur Wright stunned New York City—and the new aviation world—with his flights over New York Harbor and the Statue of Liberty.

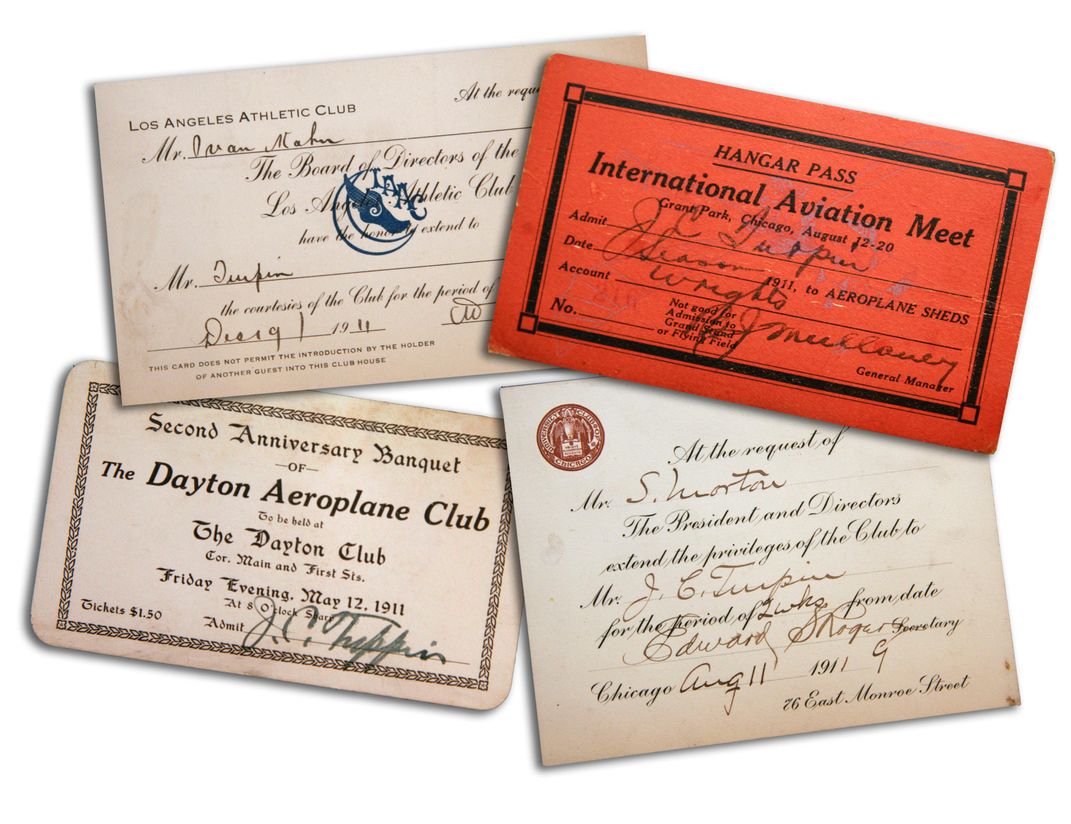

In 1909, Turpin abandoned his promising career in the family business to help the Wrights improve their engines. He began taking lessons at the Wright Flying School in August 1910, while the first crop of Wright pilots was out on the road. He soloed right after Phillip Parmelee, a chauffeur from Michigan, and the two joined the Wright Exhibition Team. So began their partnership.

Fast forward more than a century later. I visited Clifford Turpin’s grandson Rich French and his wife Sue in their bright living room on Cape Cod. I’ve been researching and writing about early flight for decades and learned about Clifford Turpin in 2008, when I was working on an article about the Wright Exhibition Team. Turpin had died in 1966, and was survived by his daughter, who lived in a small Massachusetts town. I looked up the telephone number, called, and explained I was looking for information about Cliff Turpin. After a pause, a man replied in a brisk Cape Cod accent: “Yup. That was my grandfather. I got all his stuff. You want to see it?”

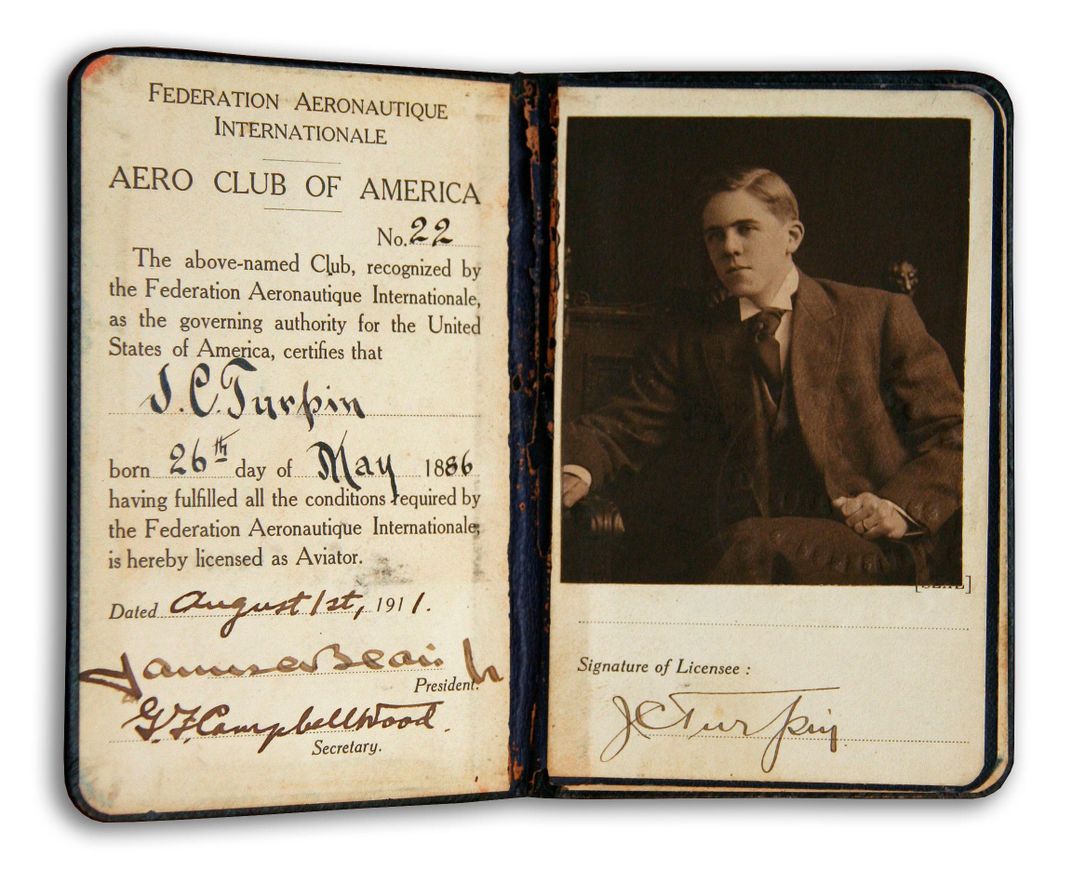

Rich and Sue are looking at two very different pictures of Turpin. One is on Turpin’s pilot’s license, issued by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. “That’s Grampsy,” Rich said, cradling the tiny document. Turpin looks out calmly, sitting in a formal pose with a business suit and hair slicked back in late Victorian style. The other picture was taken 40 or 50 years later. A ruddy-faced Turpin sits on a flowered-print sofa, smiling and holding up his customary PM whiskey. This is how Rich remembers him. “He’d be sitting in his chair having a PM, my brother and I would be sitting on the couch watching rock ’em sock ’em fights on TV. He used to love that.” But there was much Turpin didn’t reveal. “He was very friendly,” said Rich. “He would regale you with some of his tales—but never flying. I remember he would have invitations to fly down to some of the Early Birds events. He’d have nothing to do with it.”

What Rich knows about his grandfather’s early life comes from a remarkable collection, cared for by Rich, his wife Sue, and his brother James. The family has vowed to never sell or break up the collection. Turpin left behind hundreds of pictures, clippings, ribbons, country club invitations, postcards, and more. Rich’s favorite item may be the fragile Vin Fiz pennant that Cal Rodgers, who made the first flight across the continental U.S., must have given his grandfather.

The heart of the collection is a large, densely packed scrapbook. The very first item in it is a skinny newspaper clipping, dated August 1910, with a photo of an equally skinny Cliff Turpin under the headline “Society Man to Turn Aviator.” Turpin was 24.

It didn’t take long for the new aviator to start performing. In the scrapbook, a button with a crumpled blue ribbon heralds his first gig: Parmalee’s backup pilot at the Parkersburg, West Virginia Centennial Celebration from September 5 to 10. Next to the ribbon is the story of Turpin’s first performance at the Missouri State Fair, in October 1910, where he showed off “sensational ‘ocean dips,’ figure eights, and a race against an automobile.”

In the fall of 1910, Turpin was by far the junior member of the team, not making nearly the headlines of teammates Walter Brookins, Arch Hoxsey, and Ralph Johnstone, who had set distance and altitude records. After being spread all over the country that summer, the Wright pilots gathered in October for the biggest meet of the season: Belmont Park in New York. It was here that the Wright brothers hoped to reduce Curtiss and all others, foreign and domestic, to minor contenders in the Gordon Bennett Cup.

The Wright team arrived with the Baby Grand racer. Several pages in the scrapbook are devoted to pictures of it. There stands Turpin holding a wingtip of the tiny airplane—half the size of an ordinary Wright Flyer, with double the power. Orville Wright grimaces as he grips the controls before a flight test, and a scrum of men hold it back by the tail. Back in Dayton Orville had flown it to near 80 mph. It had to win; the Wright team was up against high-powered Blériots, Farmans, and Curtiss types. (Curtiss himself also brought a racer, but he had technical trouble and couldn’t get off the ground.) Brookins was chosen to race the Baby Grand, and was the odds-on favorite. But just as he started the race, his engine quit. Moments later, the airplane was a balled-up mess of wire and wood, with Brookins groaning in agony nearby.

Up to this point, the Wright team had enjoyed great success, especially financially. But after Belmont Park (and despite Johnstone’s flight achieving an award-winning altitude of 9,714 feet), the Wright team struggled. Then came a pair of tragic losses.

It’s all in the scrapbook. Turpin kept formal portraits of Arch Hoxsey and Ralph Johnstone at the controls of their airplanes. Both look supremely confident. Hoxsey looks deeply into the camera. To the side is Johnstone, jutting out his chin. Then there’s a shot of a crumpled Wright Model B on the ground, taken a month after Belmont Park. It’s taken from one wingtip, looking inside the mangled mass of airplane. On the back is a pencil inscription: “Ralph Johnstone killed in crash in Denver Colorado.” His wings had crumpled mid-air. A month later, on December 26, 1910, Hoxsey bested his late teammate at the second Dominguez Field Air Meet by rising to 11,474 feet above Los Angeles. Turpin kept a souvenir postcard of Hoxsey, looking bold in a heavy fur-lined leather coat to protect against the cold at altitude. The postcard’s inscription couldn’t be simpler: “The Late Arch Hoxsey.” On New Year’s Eve, Hoxsey plunged into the ground head-first from about 7,000 feet.

Turpin missed it all. He was preparing for his next appearance, which harked back to his salesman days. In January 1911, he represented the Wright Company at the New York Aero Show at the Grand Central Palace in New York City. He kept the engraved invitation sent to his parents. It was the only bright spot on the Wright team 1911 calendar.

The year began miserably for the Wright pilots. Team manager Roy Knabenshue resigned, fallout from the earlier deaths of Johnstone and Hoxsey. No exhibitions were scheduled. Turpin came home to Dayton and became an instructor at the Wrights’ flying school. He wasn’t the best teacher, but it was a year of illustrious students. In May, Orville reported to Wilbur (who was on business in Europe) that “Turpin and [Al] Welsh are training our new men. The men trained so far this year are: Gill (13 lessons, 2 hours, 18 minutes), Lieut. [John] Rodgers, of Navy, [Oscar] Brindley, and Bonney…. Lieuts. [Henry “Hap”] Arnold and [Thomas] Milling of the Army are just starting their lessons.” Arnold and Milling (trained by Welsh and Turpin, respectively) would both rise to the rank of general, and Arnold became the commander of the Army Air Forces in World War II, and the U.S. Air Force’s only five-star general. John Rodgers, the Navy lieutenant, later became famous for an attempt to fly to Hawaii.

Rodgers was one of Turpin’s students, and the letters he wrote home about his training had a positive tone that inspired his cousin Cal, who was also looking for an adventure. John and Cal came from a long line of naval heroes dating back to the Revolution. Due to deafness, Cal could not serve, so he came to Dayton to learn to fly, and soon set his sights on making the first flight across the United States. Given Orville’s assessment of Turpin’s instruction, Cal was fortunate to get Al Welsh as his teacher. “Welsh is, on the whole, our best teacher,” Orville wrote to Wilbur in June. “Operators under him learn to bank properly. Those taught by Turpin simply slide around the curves.”

Orville once marked out the area of a half-mile track so the pilots could practice staying within the confines of a typical show ground. Turpin couldn’t do it. Nevertheless, he was sent back out on the road. Orville and Wilbur didn’t have much choice.

Turpin’s first engagements of 1911 were indicative of the state of the Wright team. Curtiss’ team had cut their prices. Knabenshue (who in March had been coaxed back to managing the team) had a hard time getting guaranteed high-paying shows. Brookins was falling out with the Wrights, and showed signs of mental imbalance. Turpin and Parmelee were now the mainstays of the team. Orville continued to worry. He reported to Wilbur that Alpheus Barnes, the Wright Company’s New York manager, had gone to Hartford, Connecticut, to see Turpin fly. “Barnes was completely disgusted with Turpin’s flying,” he wrote Wilbur. “Turpin was as nervous as [Wright pilot Frank] Coffyn was last year.”

The scrapbook has no hint of a lack of confidence. The next year mostly appears to be an amazing romp.

While exhibitions were quickly becoming a losing business proposition for the Wrights and many others, they still made pilots into celebrities. When Turpin and Parmelee arrived in Colorado Springs in August, the news was reported with typically breathless hysteria. “Revelers Riot Through Springs Streets” screams a headline; “20,000 Shout as Aviators Dip in Treacherous Air; Girls Try to Hug Birdmen After Death Defying Flights.” Even better, Parmelee and Turpin made the trek (by road) to the summit of Pike’s Peak, building anticipation that they would later attempt to reach the summit by airplane. A cartoon on the front page of the Colorado Springs Gazette showed a bearded mountain shaking hands with a pilot whose airplane carries the banner Pike’s Peak or Bust. But there’s no report that the mountain was actually conquered. Bust it was.

In Peoria Turpin created a PR mini-disaster. The headline in the October 8, 1911 Peoria Sunday Journal reads: “Numbed Almost to Insensibility, Intrepid Aviator is Forced to Give Up Flight That 85,000 Peorians Waited to See.” Almost the entire front page was taken up with three different retellings of Turpin’s aborted trip from Springfield. One account had Turpin’s byline. After waiting until after 3 p.m. for rain to clear in Springfield, Turpin got pushed around by a cold wind so strong that at one point his Model B stopped flying forward. Thirty miles from Peoria, he gave up. The next day a headline proclaimed he had arrived in the town, but the 85,000 Peorians has dwindled to “Small Group of Aviation Bugs Huddle at Mile Track to See Great Wright Pupil Finish Trip.”

Still, the show had to go on.

In November 1911 the Wrights dissolved the exhibition team. As the mementos in the scrapbook show, Turpin and Parmelee went freelance, renting a couple of airplanes from the Wright Company. For $4,726.90, they got a used Model B and Model EX, spare wings, props, parts, and “1 complete tent and sledge.” Turpin also kept a contract for the three-day Aero-Military Tournament, in Louisville, for which the pair were guaranteed 50 percent of the gate or at least $1,000.

By January 1912 Turpin and Parmelee had made their way to Los Angeles, where their presence was heralded by one of the most striking headlines of all: “First Bandit Chase Through Air, Aviators Fly Over the Foothills.” The January 12 Los Angeles Evening Herald carried a huge picture of a very solemn-looking Parmelee and Turpin being deputized by Sheriff Dave Larimer. The paper reported that two bandits in Burbank shot a deputy marshal and were on the run. Flying from Dominguez Field with pilot Howard Gill and airplane builder Glenn Martin, the two airmen headed into the fog toward San Fernando, supposedly to flush the outlaws from the bushes. According to historian Carroll Gray, it was all a stunt. At the third Dominguez Air Meet, just over a week later—which organizer Dick Ferris said would have more entertaining than scientific flying—one of the most novel contests was something called “ ‘Man Hunt’ by deputized aviator.” Parmelee won.

California offered all sorts of new experiences. The scrapbook has a poster for nine Sundays of “Free Aviation” at Venice Beach with “The Famous Aviators Phil O. Parmelee and Clifford Turpin.” “Professor” Charles Saunders (a.k.a Grant Morton) dropped parachutists from the Model EX. After each demonstration they sold rides—a “nice source of income,” Turpin wrote to Orville Wright.

The two fliers got a movie gig too. A large photo shows Parmelee in the rented Model B with a gun. Next to him, aiming a pistol, is Mabel Normand, the leading lady of Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios. The image is a still from Sennett’s comedy Dash Through the Clouds, filmed that April at Dominguez. It’s a lousy film, but has the best surviving sequences showing the Wright Model B flying, and the only known film of Parmelee. He played Slim, the aviator who steals Mabel’s heart.

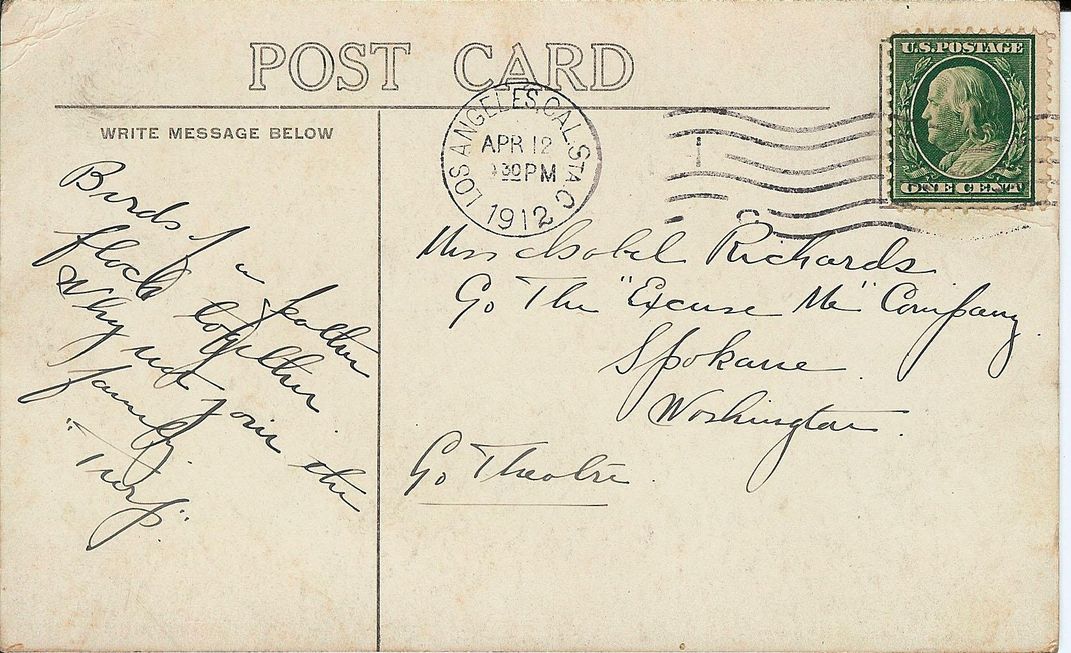

Turpin’s life was imitating Parmelee’s art. One of the collection’s treasures is a postcard postmarked April 12, 1912. Turpin mailed it to a Miss Isabel Richards, an actress in the touring company of a comedy called Excuse Me. When the two met, love clearly bloomed. Turpin wrote a simple proposal on the postcard’s back: “Birds of a feather flock together. Why not join the family?” Richards said yes.

When their lease with the Wrights ran out, in May 1912, Parmelee and Turpin acquired two new tractor biplanes from Jay Gage of Los Angeles. They went north, and split up. Parmelee went to North Yakima, and Turpin went to Seattle.

The collection has only two images of Turpin with his Gage biplane, both taken on May 30, 1912, at the Meadows race track in Seattle. It’s his last flight. The first shows him guiding the airplane on the ground, getting ready to take off. The second shows the flight’s horrifying end a few minutes later. The airplane is lurching into the grandstand as spectators flee in opposite directions. As Turpin had taken off, a photographer had stepped directly in front of him. Turpin swerved and clipped a pole, which pivoted him into the crowd. One spectator was killed and more than a dozen injured. Turpin was dragged from the wreckage, conscious and not seriously hurt.

The tragedies weren’t over. The next day came word that Wilbur Wright was dead of typhoid fever, and another spectator injured in Turpin’s crash—a boy—had died. The day after that, Parmelee was killed, his Gage flipping over in a high wind. Turpin retrieved his best friend’s body and returned it to Parmelee’s family in Michigan.

Rich picked through a neat stack of letters that form a poignant postscript to Turpin’s brief career. At the top of the pile is a typewritten, four-sentence note dated December 27, 1949. “Dear Cliff,” it begins, “This breaks the silence of 38 years.” It’s from Hap Arnold. The recently retired general reached out to his old friend from the Wright School days. As reclusive as he had become, Turpin was moved to reply; the next item is a handwritten note from Arnold dated January 13, 1950. “Dear Cliff, It was awfully good to get your note. I had followed your career up to your unfortunate trouble in the north west. Then a blank.”

Nothing in the collection explains the blank. Turpin sold cars in New York for a year, then moved to Boston and went into the cotton waste business, achieving some success. Rich and Sue know only some of the story. “He ended up retired, and to my knowledge, not doing anything,” says Rich. “Cliff and Isabel were one of the richest families in town,” adds Sue. In the 1920s, the couple adopted Sally, Rich’s mother. “Then the crash came in ’29 and they became so poor,” says Sue. “[People] said that Isabel couldn’t adjust.” One day in 1945, when Rich was two, Isabel committed suicide. Turpin withdrew further. “It’s like he checked out of society,” says Sue. “Nobody even knew that he flew.”

When Turpin wrote back to Hap Arnold, he was making a rare connection to his past. After receiving Turpin’s letter, a delighted Arnold quickly wrote back: “It would be grand to see you again, —to get together with you and Frank [Coffyn] and Walter [Brookins] for a little hangar flying.” But the typewritten letter is unsigned. Clipped to it is another note, from M.R. Stover, Arnold’s secretary. “I am as deeply grieved to send this to you, unsigned, as you will be, to receive it.” Arnold had died the day he wrote the letter. Turpin went silent again.

Rich now cherishes his grandfather’s story in a way he couldn’t while growing up. “It was no big deal [then]—I was a kid! I had to take care of the cows. So Grampsy flew with the Wright brothers—fine. But the older you get, the more you go ‘Wow! That’s pretty cool.’ ”

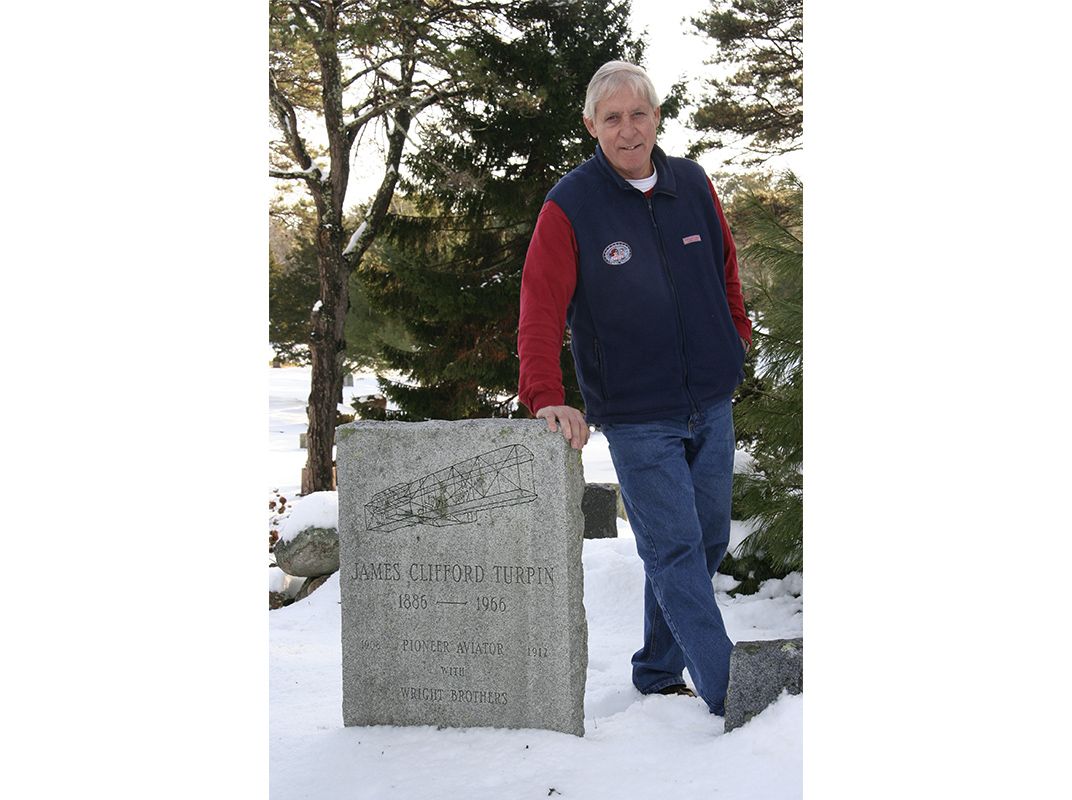

Rich took me to see the cottage where Turpin lived, and the cemetery where he’s buried. Turpin’s headstone features an engraved Wright Flyer—the one thing almost no one knew about him.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/10/94107ce5-41ac-4bee-8968-671631fdc219/09d_on2015_jct_078_live.jpg)