Glamour Boy

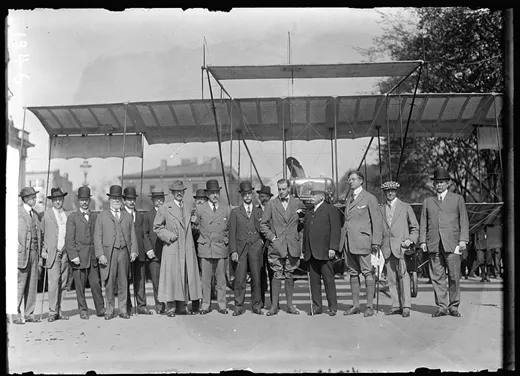

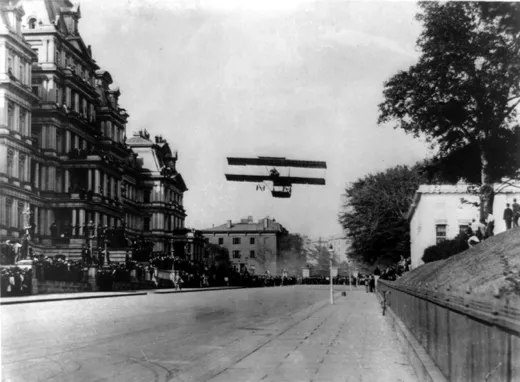

The day Claude Grahame-White thrilled the crowd at the Boston-Harvard meet.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/grahame-white-flash.jpg)

The Wright brothers loathed the sight of Claude Grahame-White. It wasn’t just the Englishman’s smirking—though undeniably handsome—face that riled the brothers. It was his swagger, his lifestyle and his love of self-publicity. What really drove Wilbur and Orville mad was that in their eyes, Grahame-White was a charlatan, a man who knew nothing about aeronautics except that it was a good way to make a fast buck.

As for Grahame-White, he viewed the Wrights as a pair of po-faced schemers who deserved praise for their invention, and scorn for the way they filed suit against every other airplane manufacturer. The Wrights may have given aviation to the world in 1903, but Graham-White would give the world what it now wanted—entertainment.

He first crossed the Wrights' path in the summer of 1908. Wilbur was in Europe to show the skeptics their invention, and the Englishman stood open-mouthed among the crowd at Camp d’Auvours in France. After he was introduced to Wright following the demonstration, Grahame-White described him as an “ascetic, gaunt American with watchful, hawklike eyes.”

At the age of 29, Grahame-White returned to England determined to fly. Up until then his thrills had come from automobiles and speedboats (both of which he used to impress his many lady friends), but now his attention turned to aviation. He ordered a machine from Louis Blériot’s factory in France and taught himself to fly. The news that he had soloed without a single lesson received widespread coverage, which made him realize aviation’s potential for achieving instant fame. He hired a press agent in early 1910 and instructed him “to circularize the whole of the British and foreign press to give the flights [of mine] every publicity.”

Soon Grahame-White was one of the best-known faces in Europe. Aviation meets were all the rage, and every promoter in town wanted his event to be graced with the dashing Grahame-White. Here, finally, was a charismatic performer, different from the grim-faced fliers who were more scientists that showmen. King Edward VII requested a private demonstration of the flying machine, but then died before Grahame-White could oblige. Instead the airman toured the country’s meets, collecting more than $75,000 (equivalent to approximately $1,200,000 today) in prize and appearance money.

Grahame-White’s exploits didn’t go unnoticed in the States. Aviation meets were picking up in popularity, and when J.V. Martin of the Harvard Aeronautical Society came to Europe in the summer of 1910 seeking aviators to compete in the Boston-Harvard Meet, the name at the top of his wish list was Claude Grahame-White. He got his man with the promise of a $50,000 retainer and all expenses paid.

Grahame-White arrived in Boston on September 1 to a quayside lined with reporters and fans. One female journalist, Phoebe Dwight, warned Boston’s menfolk to be on their guard if they took their sweethearts to the airshow: “For before you know it these hearts may be fluttering along at the tail of an airplane wherein sits a daring and spectacular young man who has won the title of the matinee idol of the aviation field–Claude Grahame-White.” Dwight’s prediction was on target: By the end of the Boston-Harvard Meet women were falling over themselves to take a short ride with the famous airman. The Englishman, whose love of money was as ardent as his love of the fairer sex, charged $500 for a five-minute flight.

But Grahame-White wasn’t in America just to snatch the money and thrill the girls. He was also a competitor, intent on winning races against other fliers. In Boston he claimed the blue ribbon event, the 33-mile race from the airfield to Boston Light (in Boston Harbor), for which he won $10,000.

That feat brought him to the attention of President Taft, who attended the meet one day but jocularly declined to put his own 250-pound frame into a flying machine. The Mayor of Boston, John Fitzgerald (grandfather of JFK), did accept an invitation to fly with Grahame-White, however, and later presented him with a silver loving cup on which was inscribed: “From Boston Friends, in admiration of your skill and sportsmanship as an aviator.”

From Boston, Grahame-White went on to Belmont Park in New York to compete for Britain in the International Aviation Cup, which the American Glenn Curtiss had won the previous year in France. With Curtiss absent this time around, American hopes rested with young Walter Brookins in a Wright biplane. Another American, the fearless John Moisant, was also expected to do well, but neither they nor France’s Alfred Leblanc could prevent a Grahame-White triumph in his Blériot.

Grahame-White remained in the States for another month, basking in the limelight and courting pretty Pauline Chase, one of the country’s most famous actresses. Then, shortly before he was due to depart for England, he was summoned to appear before a circuit court judge. The Wrights had filed suit, accusing Grahame-White of breaching their patent. The brothers demanded a full accounting of his earnings in America, every last cent of the $82,000 that he’d won.

Grahame-White ignored the summons and slipped out of the States on an earlier boat, laughing to reporters back in England that “the Wrights are frightened. I’ve scared them so bloody well that they are terrified. I’m their most formidable competitor and they know it.”

Two weeks later, on December 18, Grahame-White was badly injured chasing a $20,000 prize for the longest nonstop flight from England to the European mainland. It was while he lay in a hospital bed that he weighed his odds of surviving such a dangerous profession. Hardly a month passed without another aviator falling from the sky, and it seemed just a matter of time before his own luck ran out. So he quit competitive flying and plowed his money into creating the Grahame-White Aviation Company and London’s first aerodrome at Hendon. A few years later he sold the aerodrome to the British Government for more than $1,000,000.

Grahame-White died in the summer of 1959 at the age of 79—one of the last survivors of the pioneering days of aviation. While he’d never had the inventive mind of the Wrights or the vision of Glenn Curtiss, his role in early aviation was nonetheless important. Grahame-White got the ordinary Joe interested in aeronautics, and helped to glamorize a business dominated by engineers. In short, to use a modern word, he made aviation sexy.

Gavin Mortimer's books include Chasing Icarus: The Seventeen Days in 1910 That Forever Changed American Aviation.