The World According to Gottorf

The bizarre history of one of the world’s earliest planetariums.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/84/be843994-544d-4663-b797-00dd973bfcaf/871px-gottorfer_riesenglobus.jpg)

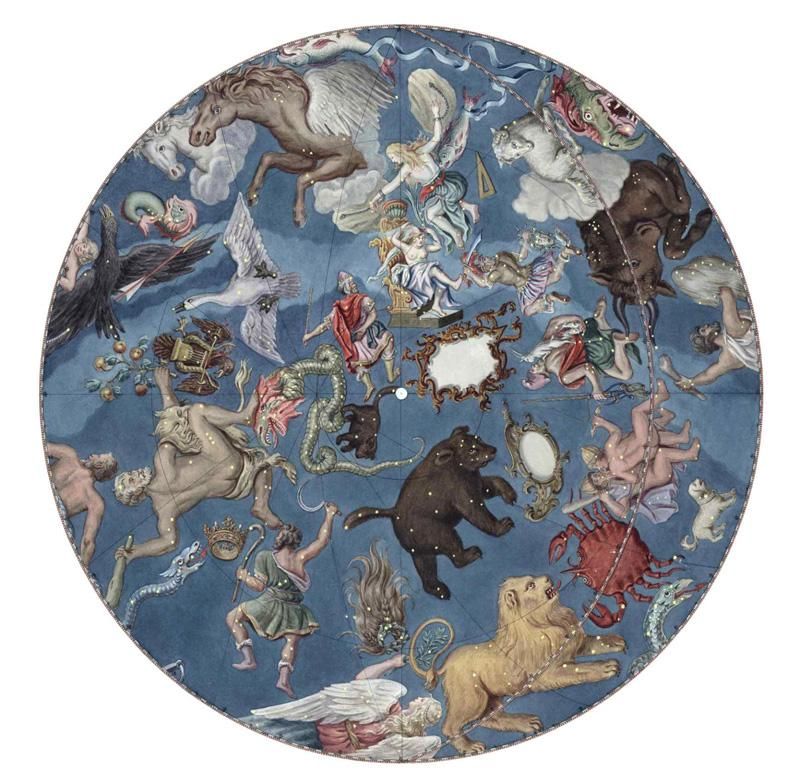

It seems unlikely that a 10-foot-diameter globe would become a world traveler, but the Gottorf Globe was no ordinary sphere. It was built over many years, probably between 1650 and 1658, for the Duke of Holstein, Frederick III. It was a combination of terrestrial and celestial globes; on its exterior were painted continents and oceans, while the interior featured constellations. As many as a dozen people could enter the globe; once everyone was seated at a table, a lever was triggered and the globe would rotate. A ring in the globe’s interior marked the horizon and allowed visitors to watch stars rise and set as the globe turned.

The globe’s construction was overseen by Adam Olearius, who had seen a similar globe—with interior seating—in Persia. The Duke and Olearius must have been enamored with that country; the building erected to house the globe was also built in the Persian style, according to cartographer Oswald Dreyer-Eimbcke, who in a 1990 article wrote that it “must have looked a bit curious in this Nordic landscape.” Despite its beautiful home, the Gottorf Globe was about to begin its bizarre, extended travels.

In 1713, when the Duke lost his territory in one of the many Northern Wars, writes William Firebrace in Star Theatre: The Story of the Planetarium, Peter the Great of Russia claimed the globe as a spoil of war. “For over four years it travelled by ship and sledge to St. Petersburg, where it was placed in the elephant house—the elephant sadly having died,” writes Firebrace. There, “the Tsar often scrutinized the globe in the mornings,” according to the Kunstkamera museum’s website, which also has a terrific virtual tour of the Gottorf Globe.

The globe was later moved into the tower of the museum (where it resides today), but in 1747, the globe was almost completely destroyed in a fire. At the time of the fire, notes Dreyer-Eimbcke, the globe’s door, painted with a coat of arms of the Duke of Gottorp-Golstein, was being stored in the museum’s basement; it is the only completely intact part of the globe to survive.

When the globe was restored, its exterior map was drawn with completely up-to-date sources, and was inscribed in Russian. The interior featured the gilded heads of 1,016 nails, depicting all then-known stars. The restoration took decades; during its repair, the globe was placed in a pavilion built especially for it. By 1901 it was put on display in the palace at Tsarskoye Selo. During the Siege of Leningrad during World War II, writes Firebrace, “the globe was seized by the German Army and transported on a specially constructed railway wagon back to Germany, where it was put on display in a deserted hospital near Lübeck, not far from its original location in Gottorf. At the end of the war, now badly damaged with bullet holes, the globe was repatriated via Murmansk to Leningrad. Photographs from 1948 show the globe on a truck, and then being raised up on a rather unstable looking system of pulleys to the top of the tower of the Kunstkamera, the wall of which has been partly demolished to get it in.”

The globe underwent another restoration, which was completed in 1958. “The Gottorf Globe led to other, less aristocratic, astronomical spheres,” writes Firebrace, including one built by German mathematician Erhard Weigel in 1661. While that globe was demolished in 1692, it led to Weigel’s “Sternschränken, or star cupboards,” writes Firebrace, “darkened shafts in which up to 100 people could enter and look up to see the actual stars.” These efforts, in turn, led English astronomer Roger Long to build a globe in 1765 that “was rotated by a winch and supposedly capable of holding 30 people,” says Firebrace.