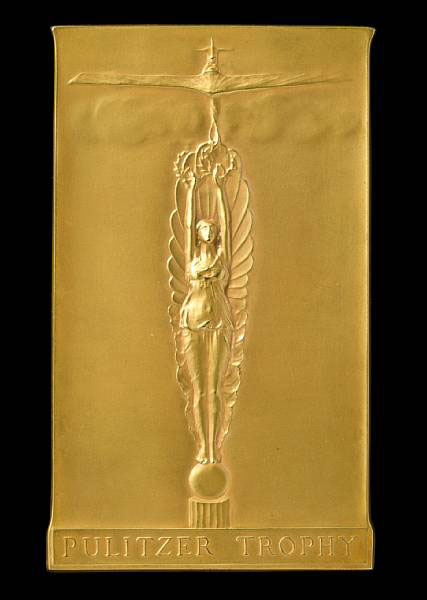

Going Once….The 1920 Pulitzer Race Trophy

“Never in the history of official flying in America has a man traveled with such great velocity”

![]()

From the Chicago Daily Tribune, November 28, 1920: “At last the pride of the Army air service, the Verville-Packard chasse biplane, has established its worth by romping ahead of thirty-four starters in the first Pulitzer trophy aeronautical race, held Thanksgiving day at Mitchel field, Mineola, .” The airplane was piloted by Lieutenant Corliss C. Moseley, who flew the course in 44 minutes and 29 seconds: “Never in the history of official flying in America has a man traveled with such great velocity,” the paper reported.

First Prize from the first Pulitzer Air Race, awarded to Lieutenant Corliss C. Moseley in 1920. Courtesy Bonhams.

The race met with great enthusiasm. “A wonderful showing,” exclaimed Charles Dickson, the president of the Aero Club of Illinois. “Why, I tell you that before the middle of next summer our skies will be filled with planes…. We’ll have passenger and express lines stretching out from Chicago like the spokes of a giant wheel. Everybody will be flying.”

Finishing second was Captain Harold Hartney, who completed the course in a Thomas-Morse scout in 47 minutes and 3/100 seconds. Third was Albert “Bert” Acosta—the only civilian—in an Italian Ansaldo S.V.A. More than half the race finishers flew de Havilland DH-4s, aka “the flaming coffin,” nicknamed for its temperamental pressurized gas tank.

The gold trophy from this first Pulitzer Air Race will be auctioned at Bonhams on Sunday, September 4, and is expected to fetch between $15,000 and $20,000. The race was the highlight of the National Air Races in the early 1920s, much like the Indianapolis 500 was for automobile fans. Sponsored by the New York World and the St. Louis Dispatch to promote aviation, the Pulitzer race ran from 1920 to 1925; the large silver trophy (listing all winners from 1920 to 1925) is part of the National Air and Space Museum’s collections.

The Pulitzer Trophy, designed by Mario Josef Korbel, exemplifies early Art Deco style. The trophy lists the winners from 1920 to 1925. Courtesy NASM.

Moseley would go on to help found Western Air Express in Los Angeles in 1924. Authors A.D. Hopkins and K.J. Evans write in The First 100: Portraits of the Men and Women Who Shaped Las Vegas, that in 1925, Western Air Express “was not yet in the passenger-carrying business.” But on one flight to Las Vegas that August, as his heavily laden biplane struggled to get off the ground, Moseley saw a hand grabbing on to the wing’s outer leading edge. The hand belonged to a 16-year-old “hobo who had been admiring the plane.” After Moseley coaxed the boy onto the wing (he was too frightened to get into the cockpit), Moseley continued on to Los Angeles where, the authors report, “the boy had been stripped of every stitch of his clothing except his cuffs and collar” by the 90 mph winds. The stowaway “was never named, but was reportedly given a train ticket back to Las Vegas.”

And some clothes, we hope.