My Pen Pals Were WWI Pilots

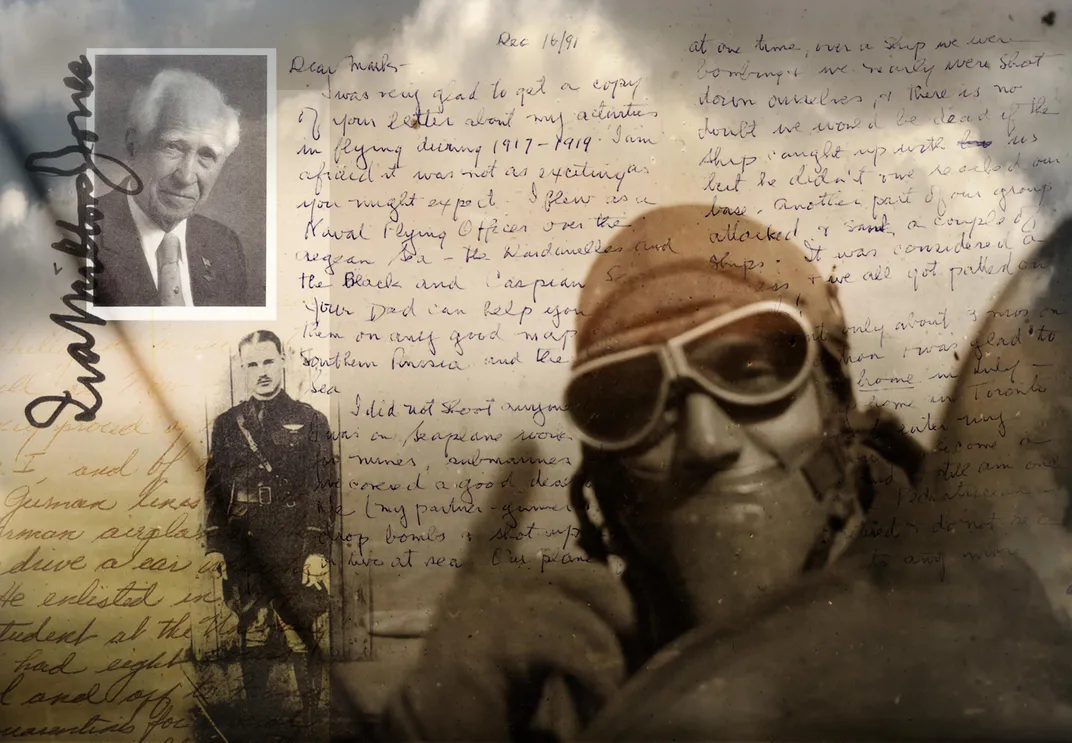

Through a long-ago correspondence, a young boy met the last living pilots of World War I.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/8a/678a85aa-1caa-4ca9-b310-f0d70887935b/07l_on2018_opener_live.jpg)

As a kid I was obsessed with World War I aviation—or with what I imagined it to be. I hung pictures of the Red Baron, built Sopwith Camel models, and played computer flight simulators while wearing homemade goggles. Around 1991, when I was 10 years old, my father suggested that I write to the League of World War I Overseas Flyers, a veterans organization of surviving American aviators from that war.

I threw myself into the task. First, I wrote what amounted to a fan letter to the president of the league, 95-year-old Captain Ira Milton Jones. Shortly thereafter, Captain Jones sent me a packet of information with a cordial, encouraging letter.

I was thrilled by having his autograph—a real World War I pilot!—but the most useful item he sent was the league roster. It was the 1986 edition, grimly updated with a red marker. Dozens of World War I Overseas Flyers who’d been alive five years earlier now had their names crossed out in red. Members who had died prior to 1986 were listed in a “Last Roll Call” of sobering length.

A poem carefully pasted to the inside cover, signed by Captain Jones, read:

I’ve lived by the side of the road

I’ve watched the race of man pass by,

I’ve kept the record of those who have died,\

And now I wonder when will I

Have my name crossed out in red

And added to the list of dead?

His somber verse did not dampen my enthusiasm. I sent letters to all 32 men whose names had thus far dodged the red pen.

To my astonished excitement, responses began arriving quickly. Some were more interesting than others, but few struck me as riveting. The men’s stories were not like my Hollywood daydreams. Photos of the near-centenarians showed them looking frail and year-worn, a far cry from the young cavaliers I imagined zooming off to duel the Red Baron’s Flying Circus, silk scarves snapping in the wind.

Captain Jones, a man of great grace and kindness, passed away in early 1992. The idea of some unknown historian crossing a red X over his name was too gloomy for me to contemplate. The energy I once felt for my project diminished, and I was uncertain what to do with the answers I’d received. I filed all the papers the veterans sent—totaling 15 sets—in a brown accordion folder. I put the folder in a box, which I put in the basement. I didn’t examine its contents again for more than 25 years.

THE THINGS THEY SENT

Recently I ran across the accordion folder while I was looking for something else. It was wedged between a half-built 1:28 scale model biplane and a pile of old pulp novels with dogfights on their covers. The folder had a moldy smell, but I soon found that the letters I’d saved glowed with a new meaning.

Now 37, I carefully removed these bundles of old men’s memories and covered a tabletop with them. There was a rainbow of paper: Christmas cards, postcards, typed letters with the errors corrected by hand, letters in the feminine script of caretakers and daughters, newspaper articles, brochures, patent blueprints, grainy copies of photographs, a card featuring a painting of a clown catching a butterfly. Most were signed by the men themselves, often in the large, zigzag scrawl of an aged hand.

I was touched by the realization that these men who had been in the dusk of their lives then—and were certainly all dead now—had taken such care to honor the request of a little kid too young yet to appreciate their generosity. All their stories and lessons were still here, though, and I was finally ready for them.

MEN AT WORK

As a kid, I’d expected stories fit for the movies. My letters even prodded the pilots to oblige with gory details. Without being unkind, none of the veterans indulged my sensationalism. They sketched their exploits humbly.

“We did not feel like heroes,” wrote Charles E. Whitehouse, who flew reconnaissance missions over the lines in France for the U.S. Army Air Service. “It was more like work. When we finished our task for the day, we were tired and were glad it was over.”

“I have never fired a shot,” wrote Ector O. Munn. “As to medals, nobody was promoted or awarded any medals while I was there.”

“The flying experience of W.W.I was not all dog-fights and derring-do,” wrote Sam Richards.

“Dog fights were very rare,” wrote Dorothy Halligan Crisp, on behalf of her late father John E. Halligan. “It was bomb or shoot and then try to make it back to the field, a futile effort often, as the planes were nowhere near what we know today.”

The few dogfight narratives in the letters mostly described near-disasters and narrow escapes. Munn wrote:

As for ‘dogfights’ in the air, the first time we crossed the line we ran into some German planes. There were six of us and [the Germans] shot down two. They almost got me and must have put 100 holes in my rudder, but I survived. On another occasion we crossed the lines with some 22 planes and 20 of us were shot down; two of us survived, one of them being myself. That would be September 25th, 1918, and was purely a matter of luck as it was very cloudy and fortunately they did not see me or the other fellow in the clouds.

Frank A. Dixon wrote of another harrowing encounter. “In one of [our] patrols we ran into an enemy squadron of new D7 Fokkers, one of our worst experiences. Only three of us returned and we were forced to regroup, new planes and pilots.”

One theme that emerged from their letters was that these pilots spent less time fighting the enemy than they did struggling with their own machines. Not even the finest aircraft of the era were a source of much comfort for their pilots. The general attitude of the correspondents was that the airplane was a tool like any other—and seldom a reliable tool.

Haddow M. Keith, M.D., flew seaplanes over the Dardanelles and the Black and Caspian seas. “We did drop bombs, and shot up a ship or two at sea. Our plane failed at one time, over a ship we were bombing, and we nearly were shot down ourselves,” he wrote.

Mechanical failures, pilot errors, and emergency landings were the centerpieces of several stories. Jenkin Hockert wrote of one unscheduled return to the ground:

I realized that I was spiraling in a slow spin. I looked at my altimeter; it registered 50 feet above ground…. I dimly saw an open field ahead and landed immediately, running into a cemetery wall, but without damage. I got out of the plane and walked around it several times, hardly believing that I had landed safely.… Looking back the way I had come, I made out a railroad station with many wires. How lucky I was to have missed them all! … Two people appeared, and with their help I tied the plane down. I was in the middle of a small town; calling the field office I found I was only 20 miles from Vinets. I stayed overnight with a French family, hearing rumors that the Armistice was to be signed the next day. Early in the morning I checked the plane, found it in good condition, and, with the help of some local boys turned it around. At 10:30 I swung the propeller and was off.

Charles Whitehouse’s 8th Aero Squadron was equipped with one of the war’s worst airplanes, the infamously unwieldy British de Havilland 4. The DH-4 did nothing to glamorize his career. Whitehouse recalled: “We did not enjoy flying because the planes that we flew were big like trucks on the ground.” The DH-4’s poor handling earned it the nickname “Flying Casket.” This aircraft was the one most frequently mentioned among the letters.

Sam Richards flew the DH-4 as well as its better-designed successor, the DH-9. He worked with British Royal Air Force squadrons to bomb German U-boats in port along the Belgian and Netherlands coasts.

Several pilots, including Robert A. Dewey and Ira Jones, spent time with the Curtiss JN-4, remembered semi-affectionately as the “Jenny.” Jones recalled meeting the JN-4 early in his training and getting to know it all-too-intimately:

[All of our Jennys] were in crates and we had to uncrate and rig them. What we did rigging them would scare the pants off of me today. When the wing-fitting holes did not line up properly we’d take a rat-tail file and line them up…. My Jenny had neither a compass nor a gas gauge. The only instrument on the dashboard was an ‘on and off’ switch. For a map I had a blue print of the area showing only major roads and railroads.

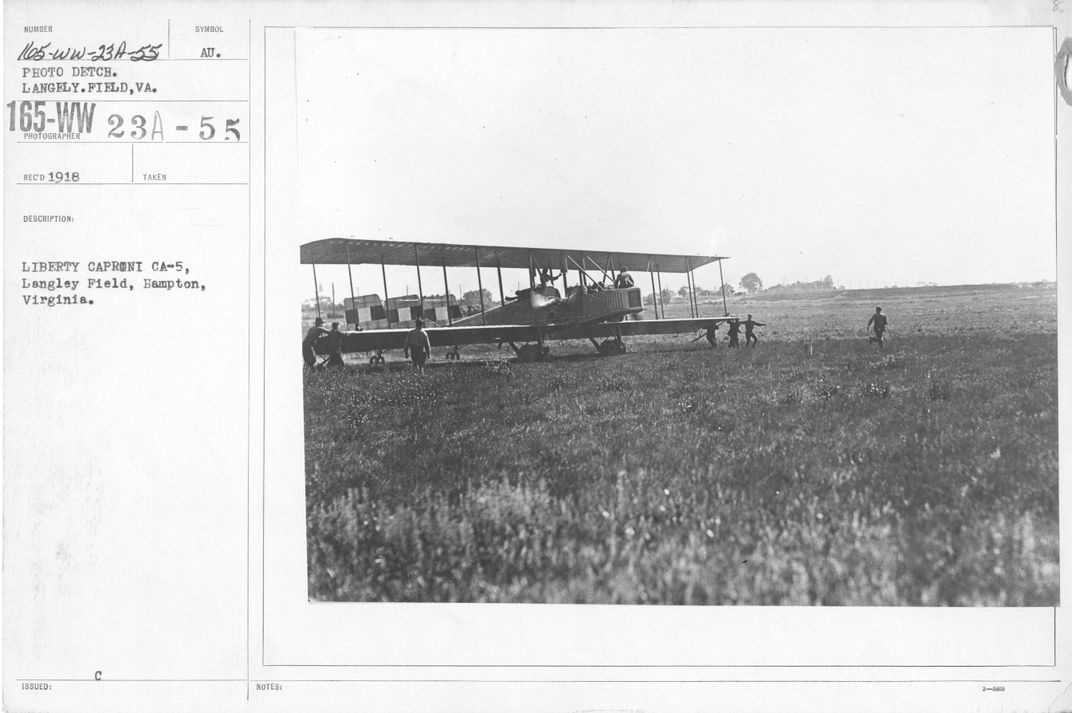

Some members of the Flyers used the French two-seater observation and bombing airplanes, such as the Salmson and Breguet, which were coveted alternatives to the de Havillands. George M.D. Lewis flew the Italian Caproni Ca.36—“the first bomber flown by U.S. airmen in combat, and the world’s first strategic bomber,” recalled his son, George Lewis Jr.

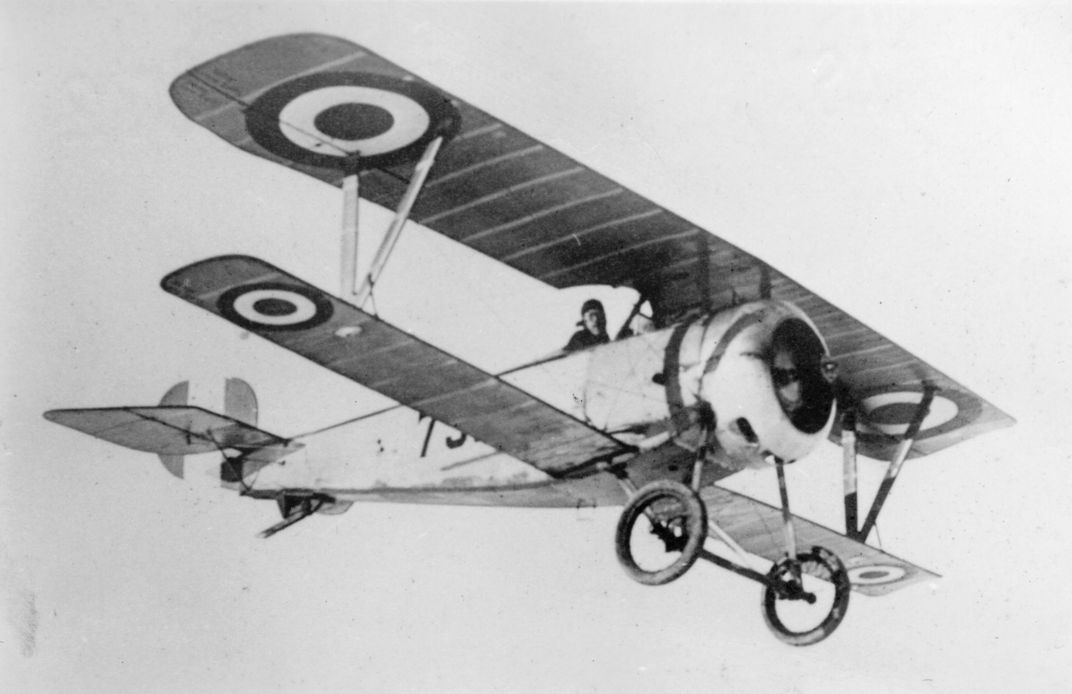

Several Flyers took the controls of the Sopwith Camel, perhaps the most famous airplane of the war, while others had flown the famed and feared Royal Aircraft Factory SE5a or various models of Nieuports or SPAD pursuit biplanes. Mr. Dixon flew some of these iconic warbirds and was a Camel devotee but admitted even this beloved airplane had its faults:

[My Camel] chewed up its engine because the oil pump seized. I landed in a farmer’s field…. There were cows around and after I returned from calling for help, one cow had put her leg through a wing while licking the castor oil that had overflowed.

When these airplanes flew well, they could work wonders in the sky. Mr. Hockert wrote: “The best part of the day was a wonderful exhibition of flying by a Frenchman in a Nieuport. Tail-slip, barrel roll, roll, loop the loop, etc.”

THE FABRIC OF LIFE

Most of the memories the Flyers shared involved bits of everyday experience, the strings of mundane moments that make up a life. Mr. Whitehouse wrote:

The sergeants who taught us marching were not flyers but English infantry, who liked to drink beer in the evening. One of them was a bossy man with a loud voice and a big mustache. The Americans thought it would be funny, when he was drunk one night, to cut off one side of [his mustache]…. What do you think he did—cut off the other side or go around looking funny on the street?

Jones sent a copy of a period newspaper reporting an early “crash landing.” While trying to impress a camp commander with his equestrian skills, Jones was thrown from his horse, despite trying to save himself by grabbing its tail. “I’m sure some of your pals will enjoy the account of my experience, as did my buddies who witnessed the event,” wrote Jones.

Munn’s self-published autobiography, World War One: France and Russia, records an incident in which the prospective officers in his squadron were allowed to advertise their rank with white armbands. The enlisted men, annoyed by this show of vanity, convinced the local French girls that the armbands indicated that their wearers had “social diseases.”

Munn also remembered everyday hassles around the airfield, such as having to compensate local farmers for crops damaged by emergency landings. He also faced some staff problems:

Another thing that amused me were the excuses that the seamstresses could find for not showing up regularly. Their jobs were to sew tears in the linen-covered wings of our planes and it seemed that there was a French law that allowed working women 24 hours off whenever their husbands came back from the front; certainly these husbands got a lot of leave while I was there.

One surprising trend I found in these letters was the pilots’ run-ins with famous people. Mr. Lewis and Clifford W. Allsopp both served in Foggia, Italy, under then-Captain Fiorello La Guardia, who went on to become mayor of New York City.

After a flight over the Alps, Lewis’s Caproni heavy bomber crashed. Recovering in a Milan hospital, he befriended one Ernest Hemingway. “Their sneaking off to races with a couple of nurses is [mentioned] in almost every Hemingway biography,” noted George Lewis Jr. of his father and the soon-to-be-famous author.

Munn was directed to the Air Service by his friend Norman Prince, a founding father of the Lafayette Escadrille. Mr. Hockert served under Lieutenant Quentin Roosevelt, son of the 26th U.S. president, killed in combat during the war.

Dewey wrote that, during an Overseas Flyers reunion in Dayton, he met the legendary Eddie Rickenbacker, America’s top ace of World War I. Robert A. Logan served with Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd on the USS Concord in 1943.

Logan, a gunner in a DH-4, also met some famous flyers he would certainly have preferred to avoid. On April 8, 1917, while serving with the Royal Flying Corps, Logan and two comrades were trapped by five Albatros D.III scouts of Manfred von Richthofen’s squadron. Logan came under attack from three of Germany’s top aces: Manfred and Lothar von Richthofen and Karl-Emil Schaefer. Bullets riddled his airplane, flying coat, and foot. “With the engine of my plane stopped, half the tail plane and one elevator on it were shot away at almost the same instant. There was nothing the plane could do but drop like a brick,” Logan recalled. He and his pilot spent the remainder of the war in six prison camps.

In May 1918, Dixon transferred into the Royal Naval Air Service 209 Squadron. Squadron captain Roy Brown was on leave. Just weeks earlier, Brown had been credited with shooting down Manfred von Richthofen. “I thought of myself anyway as one of [Brown’s] replacements,” wrote Dixon.

WHAT THEY FOUGHT FOR

Reading the Flyers’ letters again today, I get the impression that war changed them in some ways but, in other ways, left them untouched. They kept in mind their families and civilian dreams and were quick to return to them once the fighting ended. Seventy years after World War I ended, confronted with a slew of blood-and-iron questions from a child, the Flyers were quick to digress from the war to more pleasant subjects.

Haddow Keith earned a military rank but identified himself as a doctor. In his card, he described his postwar training as a pediatrician in as much detail as his days as a naval flying officer.

Ruth Hockert, answering on behalf of the late Jenkin Hockert, sent a copy of his memoir, A Lifetime of Law, an illustrated booklet outlining his family; childhood; community service with the Kiwanis, Elks, Rotary, and Masons; and his career as a magistrate. Hockert’s military service rates only a short chapter in the story of his distinguished life.

Many of the Flyers took great pride in passing down their aviation traditions. Mrs. Crisp wrote of her father, John Halligan: “He inspired two sons-in-law to enlist in the Navy and Army Air Force in World War II and a grandson in Vietnam (Navy Air Force).”

Ira Milton Jones was a Milwaukee patent attorney. He sent me a Xeroxed patent application for an “Aeroplane,” designed by Richard H. Harris, dated July 10, 1917. The contraption was little more than an engined kite, and the sketched pilot looked nervous, called on as he was to use his feet as the landing gear.

Mr. Richards left Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to enlist in 1917. He had been studying chemical engineering, and after the war he returned to this field and invented a fire-retardant chemical to be dropped from airplanes onto forest fires.

Robert Alex Anderson found his calling as a songwriter of Hawaiian music. He enclosed a red-on-white song-sheet called “Christmas in Hawaii,” inscribed with Christmas wishes to me. On the back of the page are the titles of some of Anderson’s other Hawaiian hits: “Lovely Hula Hands,” “I’ll Weave a Lei of Stars For You,” “Cockeyed Mayor of Kaunakakai.”

“Study hard—be at the top of your class like I was,” Anderson wrote me. But it’s Robert A. Dewey’s words that most echo in my mind, almost 30 years after he wrote them.

“I hope you keep up your enthusiasm for flying and some day become a pilot,” he wrote. “But I hope you will be a peacetime flyer and not have to go to war.”