The Making of an Antarctic Station

When your first five research stations get pummeled by the harsh polar environment, build one you can move.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/94/099414f8-dbb7-465d-ad3f-4c2968aec51c/p_92_credit_-_antony_dubber.jpg)

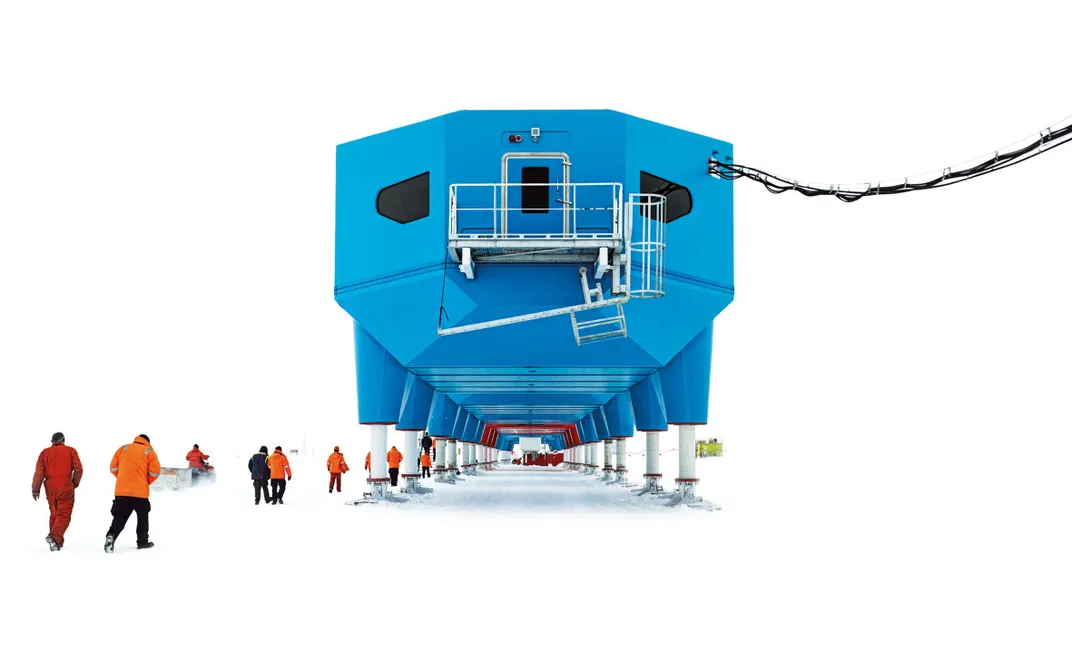

In 1956, the British Antarctic Survey established the Halley Research Station. Located on the Brunt Ice Shelf at the edge of the Weddell Sea, Halley housed scientists who studied space weather and many types of Earth and atmospheric sciences (it was a Halley science team that discovered the hole in the ozone in 1985). But they encountered a major problem: Within a decade, the station became buried and was eventually crushed by snow. So they built a second station. Which got crushed. And a third, and a fourth, which met the same demise. Halley V avoided burial, but the research teams had to abandon it too—the steel platform it was built on was anchored in ice that slowly flows from the mainland to the sea, and the station eventually strayed too close to the edge to be habitable.

So in 2004, the BAS solicited architecture firms to come up with a design that could solve all of their problems. The winner became Halley VI, a set of eight modules with hydraulic legs and skis. Designed by Hugh Broughton, it was completed in 2012. The new science facility, like Halley V, sits above the snow cover to avoid getting buried, but this version can also move toward the mainland as the shelf sloughs towards the sea. In fact, Halley VI is the world’s first fully relocatable research station. The making of Halley VI is documented in the new book Ice Station (University of Chicago Press, 2015) by Ruth Slavid, with photographs by James Morris. You can see a small set of images from the book in the gallery below.