Hawaii by Air

A new exhibit gives a rich account of the state’s aviation history.

:focal(1650x883:1651x884)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/46/a5463359-dff5-48e4-8b93-206f01a24bfb/16a_on2014_7109h_live.jpg)

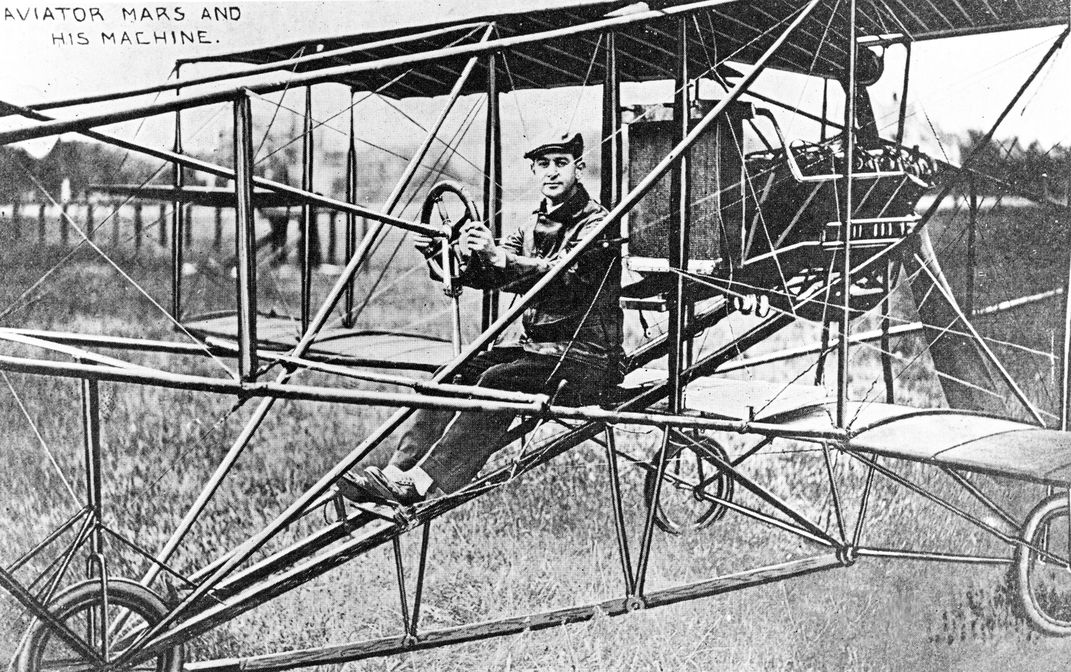

In December 1910—just seven years after the Wright brothers’ historic flights at Kitty Hawk—3,000 spectators paid to watch Bud Mars make the first airplane flight in Hawaii, taking off in a Curtiss pusher from a polo field near Honolulu. Thousands more watched from the hillsides for free, a situation that so irked Mars that he and his team—cursing the “pikers” and “deadheads”—left the islands ahead of schedule, continuing their demonstration flights in Japan.

Six months later, Clarence Walker earned the distinction of being the first to crash in Hawaii, in a Curtiss Model D. “Just because I hit a barn, a tree and a telegraph pole once in a while, it in nowise discourages me,” said Walker cheerfully.

These are just two of the dozens of stories visitors will read in Hawaii by Air, a new exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum. (The exhibit is made possible through the support of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, and will remain on display through July 2015.)

Writer and editor David Romanowski began researching the exhibit more than two years ago and, through photographs and ephemera in the Museum’s archives, was able to tell the story of air travel in Hawaii from the pioneers through the Jet Age.

“In the first part of the exhibit, I wanted to give as much space as I could to first-person accounts,” says Romanowski. Clarence Walker’s story was a “serendipitous discovery,” he says. “We had a little collection of photos taken in Hawaii of Walker, and scads of newspaper articles about him.” Walker was the first professional aviator from Utah, but Romanowski doubts that many visitors would have heard of him before seeing the exhibit.

Visitors may be more familiar with the failed 1925 attempt by the U.S. Navy to reach Hawaii from the mainland in a PN-9 seaplane, and the successful 1927 effort, in a Fokker C-2, by the U.S. Army Air Corps. The Navy aviators, perhaps more comfortable at sea, ditched more than 300 miles from Oahu. Ingeniously, the crew stripped the fabric from the aircraft’s lower wing, and sailed the airplane to their destination.

The frenzy over Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic marked a dark event in Hawaii’s flight history. The New York-to-Paris triumph inspired “Pineapple King” James Dole to offer $25,000 (the amount Raymond Orteig had offered for the transatlantic adventure, about $340,000 in today’s currency) to the first crew to fly nonstop from Oakland, California, to Honolulu. A dozen people died in the Dole Derby, which the Philadelphia Enquirer called “an orgy of reckless sacrifice.”

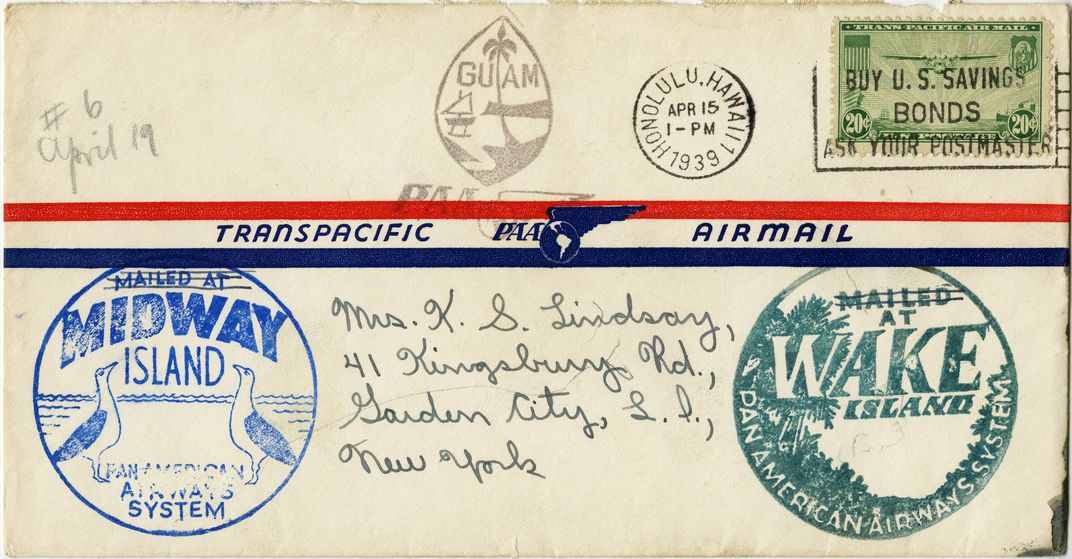

It wasn’t until 1936 that Pan Am began carrying passengers from San Francisco to Hawaii on its luxurious Martin M-130 Clippers. Richard F. Bradley paid the equivalent of $51,000 to be among the passengers on the first flight. (Bradley’s souvenir logbook is in the Museum’s collection, and is reproduced in the exhibit.) Fred Noonan was the trip navigator; he would later disappear with Amelia Earhart on their 1937 round-the-world flight.

The Clippers flew just once a week, carrying only eight or nine passengers, since cargo and mail took priority. “Really, only a few thousand people in the 1930s got to fly to Hawaii on these Clippers,” says Romanowski.

In 1939, Pan Am introduced the Boeing 314, a double-decker design with a passenger lounge and cabins in the bottom half, separate restrooms for men and women, and even a bridal suite in the rear cabin.

World War II ended the reign of the Clippers, as air travel to and among the islands—for non-military purposes—was prohibited.

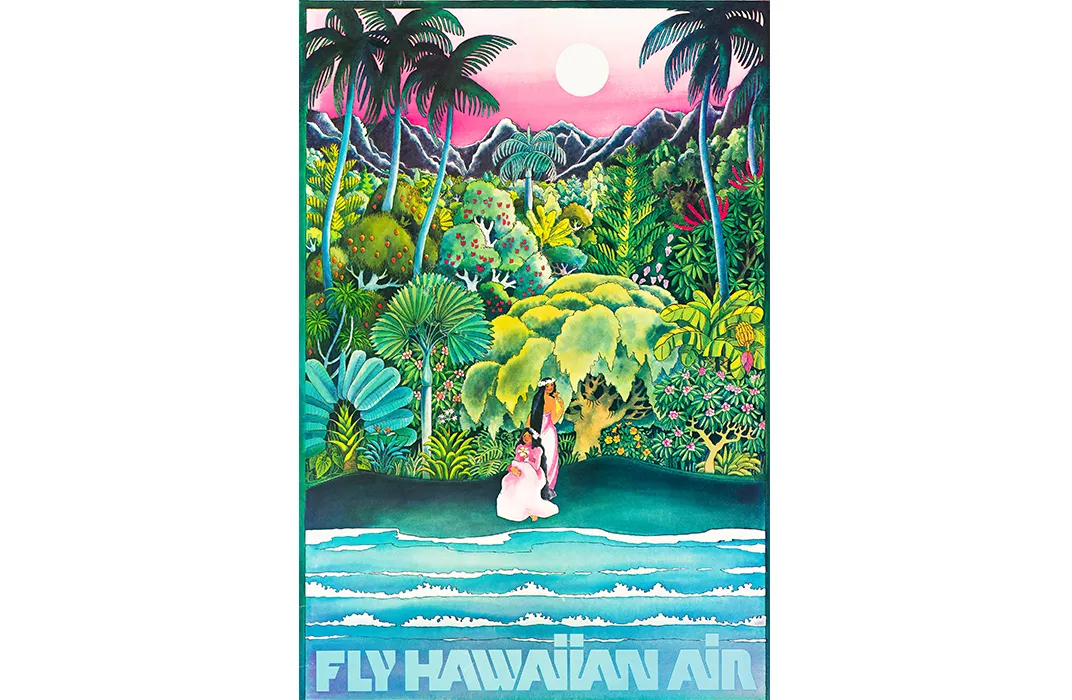

At this point in the exhibit, memorabilia—rather than first-hand accounts—tells the tale of flight in Hawaii. “It’s a story of bigger and better airplanes,” says Romanowski, “prices starting to go down, and certain spikes in travel—including post-war travel, the Jet Age, and the celebration of Hawaii’s statehood.”

In the late 1940s, Pan Am’s monopoly on overseas travel was broken and flights to Hawaii became fairly routine, something Romanowski covers in the exhibit. “The airline that opened up Hawaii to air travel a few decades later ceased operations and became history itself,” he says.

Hawaii by Air benefited from the Institution’s many divisions: “We’re the only exhibit at the Smithsonian that has live pineapples,” laughs Romanowski. “We’re really happy that Smithsonian Gardens helped us out with live plants, adding another dimension to the exhibit.”

A 1930s radio cabinet, donated by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, plays music from “Hawaii Calls,” a vintage radio show broadcast each week from the courtyard of the Moana Hotel on Waikiki Beach.

Visitors will also see a floor mosaic of the eight main Hawaiian islands, created from Landsat 7 satellite images and provided by the Museum’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies. “It’s incredibly detailed,” says Romanowski. “You can see the runaways at Honolulu’s airport, Ford Island, even smoke from an active volcano.”

Walking through the exhibit is like traveling to Hawaii—if only vicariously. It’s also a chance to learn how air travel transformed the 50th state into the tourism destination it is today.