George Abbey Had the Power

How one man ruled NASA for 30 years.

:focal(1373x330:1374x331)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/6f/4b6f9955-ed5d-4cbf-b07c-deab888e40e7/abbeycoleman.jpg)

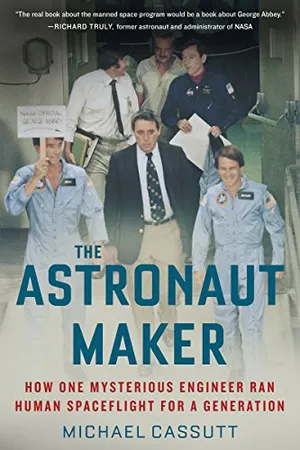

Space historian Michael Cassutt’s latest book is The Astronaut Maker. It is a biography of George Abbey, who started working at NASA as a young engineer in 1964, and quietly set about becoming the space agency’s most influential person. Cassutt talked to Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in August.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Cassutt: If you believed the rumors floating around NASA in the 1990s, you’d hear that George Abbey was all-powerful, bending the entire astronaut office and flight crew operations to his will. He was also a major power in the development of the International Space Station. Who wouldn’t be interested in digging into that?

Based on your interviews with Abbey, what are your impressions of him?

In some ways, he lived up to the legend: sly, cunning, immensely powerful in terms of individuals he knew. Yet I concluded that most rumors about his power were nonsense. In my experience, he was funny, expansive, and talkative. He is also a big-hearted family man and, from what I heard, a valuable friend. I am pleased that I had the chance to get to know him.

What are his strengths?

Intelligence would head the list. If you look at his military career, and at his first years at NASA, it’s clear that he is a brilliant man, a bit like the legendary astronaut Jim McDivitt, of whom it was said “he came in first in any class he ever took.” In addition to pure intelligence, however, he has an astonishing ability to see the big picture. His knowledge of, say, engineering was also tempered by and related to human factors. Money. Politics. In other words, he saw the total picture of spaceflight. For example, some astronauts chafed under what they considered his “paternalistic” control of their careers. They wanted to fly in space early and often—period. Abbey wanted them to fly, of course, but he also wanted them to advance their careers, to be experienced in not just space ops but program management or science, and to have decent family lives. So he would move astronauts into and out of active flight training to give them a balanced career. He is also persistent–some might even say stubborn. Once he’s made a decision or come to a position, he will hold to it and keep working it until it is accepted.

Does he have any notable flaws?

Whether by choice or nature, he is secretive. He might have taken a bit too much pleasure in shaping decisions made by those he worked for. Like anyone with authority, he enjoyed its exercise.

How did he cope with the Challenger tragedy?

The loss of Challenger and its crew was devastating for Abbey. He had not only selected and trained the five NASA astronauts, he had hand-picked a group (including El Onizuka and Mike Smith, his two closest friends on the astronaut team) who would protect and support Christa McAuliffe. He was also angry at NASA’s flawed decision-making: the appalling lapses in judgment and communication that allowed the launch to go forward that day.

He coped, as might be expected, by working harder and harder. His own family grew concerned about him during early 1986, noting that he was “never home”. By the time Abbey testified before the Rogers Commission, and as that entity’s critical report was published, he was able to move forward. But it was a dark time for him personally and professionally.

Why did former NASA administrator Dan Goldin fire Abbey?

Goldin fired Abbey for the same reason the ancients threw people into volcanoes when the crops failed. In 2000-2001, NASA was facing a looming budget over-run of $4 billion—something that was not Abbey’s fault and certainly no surprise to NASA headquarters [in Washington, D.C.]. But someone needed to take the fall, and for Dan Goldin, Abbey was the obvious choice.

Was Abbey responsible for increasing diversity in the astronaut corps?

By the early 1970s, NASA, the agency, was committed to increasing diversity in the astronaut team and in other departments. Johnson Space Center director Chris Kraft was a strong proponent of hiring women and members of minority groups. Abbey, of course, agreed with this evolution, based on his own experiences (witnessing the ugly treatment of African-American officers in the Air Force). And Abbey was the NASA official who took the lead in creating a more diverse astronaut corps, overseeing the selection of the first six women astronauts, and four members of minority groups in the 1978 group.

Do you think Abbey’s influence at NASA will ever be duplicated?

Impossible. Not only is NASA smaller and less central to human spaceflight now than it was in the Apollo era, it’s smaller than it was in the shuttle and International Space Station days. I can’t see any individual arriving at NASA with a background like Abbey’s, having the opportunity to work closely with legendary talents like George Low and Chris Kraft on programs like a lunar landing and space shuttle, then rising to center director over three decades.

(Cassutt also wrote “Mr. Inside,” a profile of George Abbey that was published in the August 2011 issue of Air & Space.)