How NASA Joined the Civil Rights Revolution

Integration came to the nation’s space agency in the mid-1960s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/13/5413932c-5b3c-46e2-a670-d7a662868c0b/01-and-we-could-not-fail-civil-rights-nasa.jpg)

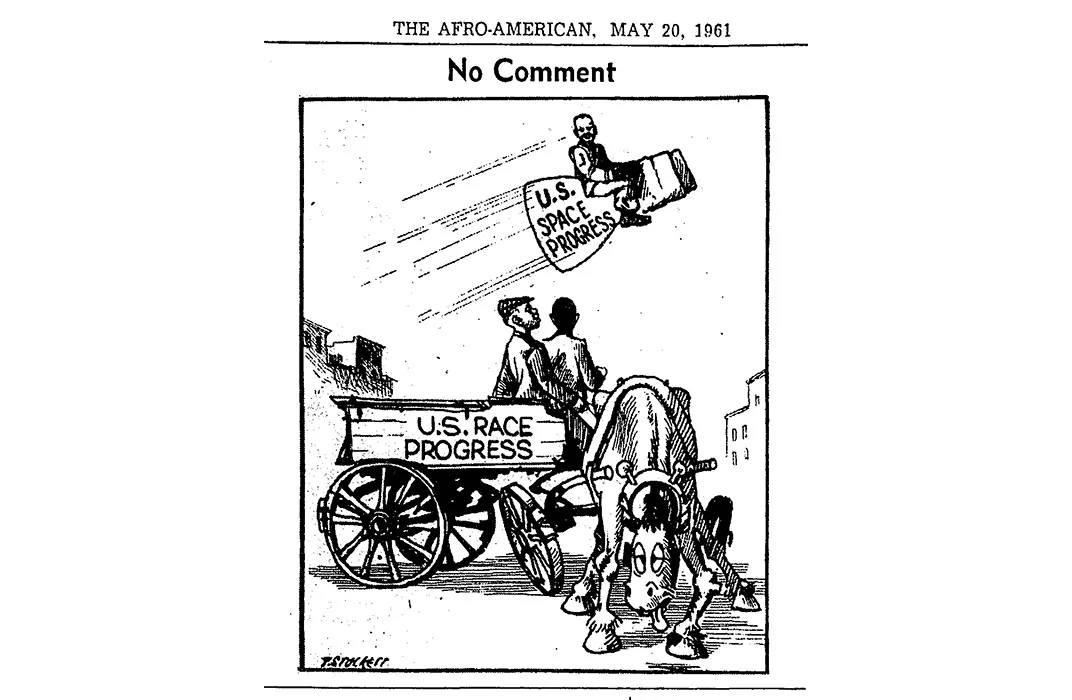

On May 13, 1961, in its first issue after Alan Shepard’s historic Mercury mission, the nation’s leading black newspaper, the New York Amsterdam News, ran a front-page column that asked a question on the minds of millions of Americans. “If you are like me,” wrote executive editor James Hicks, “as soon as you finished thrilling to the flight of the United States’s first man into outer space, your next thought was, ‘I wonder if there were any Negroes who had anything to do with Commander Shepard’s flight?’ ” History forced President John F. Kennedy to commit the country to explore space at exactly the same time it forced him to confront the movement for civil rights. Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s Earth orbit, the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, Alan Shepard’s flight, the Freedom Rides with their attendant violence and imposition of martial law, and Kennedy’s man-on-the-moon-by-the-end-of-the-decade speech all happened within weeks of one another in 1961.

More than 50 years later, few people know about the first African-Americans in the space program. They performed mathematical and engineering work at a time when laws would not allow them to use the same bathroom as their white co-workers.

Among them was a small group of young African-American men who left Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in January 1964 to work at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. These men did not lead protests or stage sit-ins (even when given the opportunity), but what they accomplished as NASA’s first black engineers was part of the civil rights revolution.

Kennedy chose federal employment as one of the tools to force integration at precisely the time that NASA and its contractors were creating 200,000 jobs in Alabama, Florida, Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. It is possible that Kennedy took this route because he doubted Congress would give him the power to do anything greater through legislation. But Vice President Lyndon Johnson, who believed the root of racial injustice was southern poverty, believed that one way to achieve racial integration was to create jobs. He thought an activist federal government could pour money into the region and bring it into the nation’s social and economic mainstream. After Kennedy placed Johnson at the head of both his National Aeronautics and Space Council and the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity, the vice president was well positioned to implement his plan. For many African-Americans who went to work for NASA, the new space program created employment opportunities that had never before been available to them.

There is a short list of steps NASA took to promote equal employment in the year before the 1964 Civil Rights Act became law: The agency created a contractors’ group in Alabama that used its money and influence to make sure African-Americans got space jobs. NASA hired Charlie Smoot, called the “first Negro recruiter” in official agency histories, to travel the nation persuading black scientists and engineers to come south. The Marshall Space Flight Center invited representatives of the historically black colleges to Huntsville in 1963, and a year later opened the agency’s college cooperative education program—in which students alternated semesters at school with semesters at Marshall—to blacks.

As a result, Walter Applewhite, Wesley Carter, George Bourda, Tommy Dubone, William Winfield, Frank C. Williams Jr., and Morgan Watson arrived at Marshall to become the embodiment of Johnson’s plan for jobs in the South.

NASA’s Cooperative Education Program

When he was young, Morgan Watson says, he didn’t have a green thumb, but had what he calls “a greasy thumb”: He liked taking things apart and putting them back together. “I worked in a hardware store,” he says, “and the white store owner saw my report card one day and saw that I had good grades in math and science, chemistry, and so forth, and he said, ‘You know, you would probably make a good engineer.’ ” Watson didn’t know what an engineer did, “so I went to the library and started reading about [them].”

Watson eventually entered the new engineering school at the all-black Southern University–Baton Rouge. By the time Charlie Smoot arrived, the university faculty considered Watson and six other young men the most promising engineering students at the school.

The seven were given exams, though Smoot reports that none of the white students who found jobs at NASA through the Co-Op program were required to take them. Once the agency was convinced the students were eligible, they were hired.

Their appointment was trumpeted by the black press: “Negro College Youth To Boost First Moongoer Into Orbit?” was the headline in the Chicago Defender. The article’s first two sentences were a snapshot of African-American hopes of achievement through the space program: “They say there’s a good chance that a Negro may be the first man on the moon. But even if he isn’t, there’s a good likelihood that Negro collegian scientists will be performing their intricate duties at the launching pad as they wave the moongoer off.”

The men warranted the attention because when they entered the Co-Op program, they became the first African-Americans engineers at NASA in the South. They also increased by five-fold the number of black professionals at Marshall, which at the time employed about 7,300 people. “I don’t even think there were any [black] clerical workers,” Watson recalls. There were “some groundskeepers and janitors, but as far as professionals, there were none.”

The white press took notice too. The New York Times called Frank Williams, the first black student hired, “a social pioneer.” It also called him “a symbol of the desires and frustrations of space agency officials in their attempts to achieve some degree of racial integration.”

Space—and Race—Progress

The idea that the Space Age might help usher in better race relations became a subject of scientific inquiry. In the spring of 1962, NASA made a grant to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences to study “the relationships of space efforts to US society.” The report proceeded, in part from the popular conception that NASA, in the academy’s words, represented “a new era of equality according to ability.” There was a belief that “communities with advanced types of industry, with their people employed in research laboratories and in the development of new engineering techniques, should display a high level of social innovation.”

The academy sent sociologist Peter Dodd to the space communities to find out if it was true. In multiple visits to Huntsville, Florida’s Cape Kennedy, and the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, Dodd spoke to NASA workers and administrators as well as municipal officials, city planners, newspapermen, ministers, educators, social workers, housewives, and teenagers.

Studies suggested that space workers had “high levels of education, which are known to be correlated with liberal views,” and that “their youth and geographic mobility have exposed them to liberal opinion.” What Dodd found was exactly the opposite, especially in matters of race. In Huntsville and at Cape Kennedy, he said, “There seem to be no evidence of strong pressure for Negro rights, nor of strong sympathy among technologists for civil rights.” To NASA workers, he found, “the Negroes appear to be an outside group presenting demands which would have to be dealt with in some way, but which are no concern of theirs.”

When the seven students from Baton Rouge stepped off the bus in Huntsville, they did not find a community that welcomed them. “There were no apartments or hotels or anything that would allow us to live there,” Watson says. “Everything was segregated.” Charlie Smoot found them rooms in homes in the black community.

Such segregation existed notwithstanding a clash two years earlier. During the months that Dodd was visiting Huntsville, the sit-in movement was sweeping America, and it did not spare Huntsville, despite its reputation as a place where “the Gospel of Wealth had more disciples…than did the Gospel of White Supremacy.” In fact, in Huntsville in 1962, two distinctly different impressions existed about the sit-ins’ impact and their severity. Ignored at the time by the local paper, the sit-ins barely registered with whites in Huntsville. Bart Slattery, Jr., a NASA spokesman, told a reporter from The Nation at the time, “We’ve never really had a problem [with race relations] here in Huntsville.” An unguarded comment made to the same reporter, however, illustrated the town’s unacknowledged racism. Asked why Huntsville was quieter than Birmingham, Montgomery, or Selma, Jimmy Walker, the manager of the Huntsville Chamber of Commerce said, “We’ve got a high class of niggers here for the most part.” While official reaction to the sit-ins was nowhere near as violent in Huntsville as it was elsewhere in Alabama, the town was no less resistant to change.

“ ‘Sit-Ins’ Finally Hit Huntsville: 23 Students Jailed in ‘Missile City’ ” was how the black Pittsburgh Courier headlined its January 20, 1962 story about the protests. “At last it has happened!” the paper said. “This famous ‘Missile City’—home of the mighty Saturn, the Redstone Rockets, Dr. Wernher von Braun, and the great Redstone Arsenal—has been hit by the sit-ins.” As in other places in Alabama, things got ugly rather quickly.

A story distributed nationally in the black press relates one racially charged incident: A few days into the protest, four African-American students, William Pearson, Leon Felder, Bertha Burl, and Mary Joiner, and a white NASA employee, technical artist Marshall Keith, walked into a Woolworth’s. Keith ordered a plate of eggs and pushed it across the counter to the black students. The Woolworth’s manager confronted Felder, who was eating the eggs Keith had ordered. “ ‘Want more salt and pepper?’ He tilted the shakers over the plate, smothering the food with condiments,” reported the Daily Defender. When Felder continued to eat, the manager started pouring ketchup all over the counter in front of the girls. When they quietly handed out tissues to one another and started wiping up, the manager grabbed the plate of eggs and smashed it on the floor.

A few days after the incident, Marshall Keith, the white NASA employee, was at home when there was a pounding on his front door. He opened it to find two men with guns who ordered him out of the house. The men blindfolded Keith, marched him to their car, and threw him in the back seat. They drove Keith to a remote section of the city, forced him out of the car, and made him strip. Then they pulled out a can of pepper spray and doused him from head to toe. The kidnappers hit him in the head with a blackjack, got in their car, and drove away. He ended up at a hospital, where he was treated for burns. He disappeared after the incident, according to Henry Thomas, an organizer from the Congress of Racial Equality who came down to Huntsville to help run the sit-ins. “We could not contact him after he was released from the hospital,” he says. “I was told his grandma had been threatened, that he had resigned his job. He left town for New York City. That was the last we heard of him.”

Thomas, who says the local police “kept a 24-hour tag on me” during the sit-ins, recalls a similar incident. On January 15, he says he noticed a strange odor in his car. “After about a block I got a stinging sensation in the seat of my pants. It was very bad. A little later I was in so much pain, I couldn’t concentrate on anything. We found a doctor and he smelled my coat and said, ‘That’s just like mustard gas.’ I was put in hospital, under sedation.”

Huntsville’s black community knew the danger, but organizers of the sit-ins—pediatrician Sonnie Hereford, dentist John Cashin, and the Reverend Ezekiel Bell—pressed on, attacking racial inequality on several fronts. While Hereford marshalled picketers to walk in front of downtown restaurants with signs saying “Khrushchev can eat here but I can’t,” Cashin and Bell distributed leaflets with news of the Huntsville sit-ins in front of the Midwest and New York Stock Exchanges. Their protest, Hereford says, “went out on the AP [wire] and quickly got the attention of [Huntsville] whose financial well-being depended on outside investment.” Not long afterward, the lunch counters and the pediatric ward at the hospital were open to people of all races.

Other public facilities, however, were still strictly segregated when the seven students arrived. In his inaugural address, Alabama governor George Wallace evoked a “separate racial station,” a concept that prevailed in Huntsville’s social sphere. “I will never forget one of the concerts that we went to,” Watson recalls. “Ray Charles came to Huntsville and there was this rope right down the center of the arena where he performed. All the whites were on one side, the blacks were on the other side.”

Nevertheless, Watson says, “there was so much going on in the black community.” When they got ready for fun, he says, “we had a lot of social outlets.” Williams had a brand-new Pontiac, and on the weekends, Watson says, “we would jump in the car and go off to Nashville or over to Atlanta.” Plus, there was plenty to do right in Huntsville. They were young. They were smart. They had jobs at NASA.

“We knew that on the social scene everything would be segregated,” Watson says. “On the work scene,” however, “that was the view of what was to come.”

What it Meant To Be First

NASA had placed the students at the cutting edge of rocket technology at Marshall. Frank Williams helped design the ground-support equipment for the Apollo program. Morgan Watson worked in propulsion, testing the Saturn 1-B, the forerunner of the Saturn V.

Regardless of how people felt about the black students, their presence caused a stir. “We were sources of curiosity by everybody,” Watson says. African-Americans at Marshall “were proud of us because we were blazing new territory for them,” while whites “wanted to know who we were and where we came from.” He remembers someone asking if he and his cohorts were students visiting from Africa. White Alabamans could not imagine that a group of young black men walking through a NASA facility in shirts and ties could be Americans.

Bourda says it was not uncommon to overhear the white Co-op students speak disparagingly. “We got a lot of them trying to come in,” they would say when they thought no blacks were around. And more to the point: “I don’t think they can cut the mustard.”

Watson said any self-doubt evaporated after he talked to the white students about their educations. “We had smaller classes, and were not taught by graduate students—we were taught by the professors themselves. We were not arrogant, but we were very, very proud of ourselves, and we liked the opportunity to be able to show that we could perform.” In fact, Watson had the chance to teach some of NASA’s engineers new skills. “I was in Southern University’s first computer programming class back in 1963, and when I got to NASA I was one of the few—including NASA employees—who were computer-literate.”

The work the students did was not just technologically groundbreaking. The space program “was the high-tech industry of the 1960s,” Watson says. Arranging for them to be there had not been easy; “We just praise NASA for its foresight to go and find African-American engineers to train,” Watson says.

As President Johnson had hoped it would, the space program opened the door for Bourda and the others. “We were determined and we had the ability to strive,” he says.

Today, there are eight engineers in Bourda’s family. “I’m proud to be the first one,” he says. “The kids—they saw what I did and they copied.”

The people who push through the door are not only the people who march. Sometimes they are the ones who show up every day, do their jobs, and show that they can handle the load. Neither the successes nor, more important, the failures of these people are simply personal: They had magnified repercussions. The black students hired through the Co-op program had to be the very best at all times. “We had heard Martin Luther King say, ‘When you start off a race behind, you have to run faster than everybody else,’ ” says Watson. As he and his fellow pioneers knew, they could not fail.