How Reno Racers Keep Their Cool

At the Reno air races, pilots know that to go fast, you have to stay cool. That’s where Pete Law comes in.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/How-Reno-Racers-Keep-Their-Cool-9-1-2012-3_FLASH.jpg)

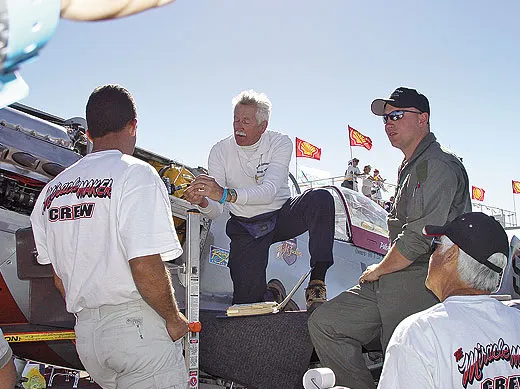

Pete Law sits in a golf cart, shaded by the massive fuselage of a Hawker Sea Fury in the pits at the Reno air races. Spread out on his knees are a binder on World War II-era Bendix Stromberg carburetors—“Required flows for metering jets”—and a hand-made chart marked “Water regulator flow bench test sheet.” While spectators snap pictures of mighty warbirds and crewmen polish already gleaming metal, he punches numbers into a calculator and takes notes with a mechanical pencil.

At 75, Law is one of the grand old men at the National Championship Air Races. Since 1966, he’s been the sage whom race teams consult in their fever to make fast airplanes faster. But air racing is not how Law makes his living. He’s a Lockheed lifer who spent four decades at the famed Skunk Works, most of them running the thermodynamics department. Though he retired in 2001, three years later a consulting firm hired him for a part-time gig on the Northrop Grumman X-47B unmanned combat air vehicle, and he’s been working on the UCAV at Northrop ever since.

But even as he was working on classified projects ranging from the SR-71 to the F-117, he was leading a second, far more public life providing engineering support for dozens of racers competing in the Unlimited class at Reno. The Unlimiteds are the racers fans love most—4,500-pound-or-heavier warbirds flown by people who revel in the reputation of aviation’s badasses. Law is one of the reasons the Unlimited racers fly as fast as they do. “Pete is the man,” says Will Whiteside, the owner of the Yak-3U known as SteadFast. “He’ll tell you ‘I’m not an engine guy’ or ‘I’m not an aero guy.’ But he knows a lot about a lot of things, and he’s got so much experience. He’s one of a kind.”

Each September, Law packs up hard-sided briefcases, cartons of books, and boxes of otherwise-impossible-to-find tools—including a sliderule, which he uses on occasion—and transforms a rented golf cart into a mobile shop at Reno Stead Field. He obsessively watches over the intricately tuned carburetors and sophisticated cooling systems he has installed over the years on warbirds that have racked up dozens of Gold trophies by racing at speeds near 500 mph. Aided by his son Vance and longtime assistant Greg Scates, Law hustles from pit to pit, dispensing advice and resolving problems.

Today is Monday, opening day at the races, when airplanes are flying qualifying rounds. Speeds clocked in these rounds will determine whether the pilots will compete in the Bronze, Silver, or Gold races; the fastest airplanes fly the Gold. After checking in with various teams, Law has parked next to the Unlimited that, as September Fury, won the Gold in 2006. Now owned by Rod Lewis, who also owns the nearby Grumman F7F Tigercat and a legendary F8F Bearcat known as Rare Bear, the Sea Fury races as 232. Although Law goes to great pains not to play favorites, this airplane is dear to his heart because it carries his carburetor, his boil-off cooling apparatus, and his anti-detonation injection (ADI) system—a Pete Law triple threat. But the airplane wasn’t making full power during practice this morning, with former astronaut Hoot Gibson at the controls, so Tigercat crew chief Jim Dale had collared Law. “We’d like to run a little bit more rpm,” he said, “so if you could come and work your magic ….”

Dale and Law agree to go 20 percent leaner on the ADI fluid, a mixture of water and methanol. After consulting the Bendix Stromberg manual and cross-referencing the data with his own charts, Law decides to replace the Number 16 drill size jet in the water regulator with a smaller Number 20, which will restrict the flow of the ADI fluid and make the engine run hotter. Limping on a bum leg set badly after he broke it in a 1973 skiing accident, he plants himself under the Sea Fury with a box stuffed with rare tools dating to the 1930s. He snips the safety wire and uses a special socket to remove the old jet. He takes off his glasses to examine it more closely, then inserts a new jet.

The fix takes about 10 minutes, but the perpetually amiable and notoriously talkative Law spends at least 20 telling Dale what he’s done. “I learned a long time ago to leave a lot of time for Pete’s answers,” Dennis Sanders says with an indulgent grin. The Sanders family, another Reno institution, is famous for Sea Furys, especially the powerful Dreadnought. “But I listen to everything he tells me, and I try my best to understand it,” Sanders goes on. “I figure that if 10 percent of it sinks in, I’m ahead of the game.”

Tuesday, Day Two

In a hangar at the east end of the field, Law is poring over a chart with Dave Cornell, the crew chief of 10-time Gold winner Rare Bear. Like most racers, Rare Bear has gone through many changes over the years, but Law helped develop its boiler, carburetor, and ADI system. The crew was expecting more than 500 mph, but yesterday’s qualifying run produced a speed of only 479.43 mph, and the highly analytical Cornell is flummoxed.

“So the induction temp is 80 degrees centigrade?” Law asks as T-6s drone overhead. “Does that seem reasonable to you?”

Cornell nods. “Oh, yeah.”

“That’s a number I would expect with what you’re doing with the jets. But the manifold pressure and the torque pressure look weird.”

“Yeah, torque per inch of manifold is cockeyed,” Cornell says morosely.

“Jeez, I’m going to have to think about this.” Law rummages through an omnipresent briefcase. “I have a chart that shows horsepower versus rpm, and it shows deriched and non-deriched fuel flows. It’s in here somewhere.”

Despite his expertise with long-obsolete piston engines, Law had never so much as seen a warbird when he hired on at Lockheed in 1959. He started working on the engineering environmental control systems on the F-104G and enjoyed the challenge. After two years devoted to Mach 2 Starfighters, he got another assignment. “Everybody on the ‘white’ [non-classified] side of the company dreamed of being ‘borrowed’ by Ben Rich to work at the Skunk Works,” Law recalls. “In 1961, he ‘borrowed’ me for six months, and I stayed for 40 years.”

Law’s first assignment was structural thermal analysis of the A-12, the Central Intelligence Agency’s single-seat predecessor to the SR-71 Blackbird. Flying at Mach 3.2, the A-12 reached temperatures up to 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, posing thermodynamics issues that aeronautical engineers had never faced. Rich, a thermodynamicist himself, was a mentor to Law and in 1980, a few years after Rich succeeded aviation icon Kelly Johnson as chief of the Skunk Works, he tapped Law to head the thermodynamics department. Long before that, though, Rich had triggered a watershed event in Law’s other career.

In the fall of 1964, Rich introduced Law to Lockheed test pilot Darryl Greenamyer. In addition to testing the A-12, Greenamyer had just flown his own Grumman F8F Bearcat in the inaugural air races at Reno. He was looking for more speed, and he thought Law could help him find it by revisiting a concept that the Germans had used on the record-setting pre-war Messerschmitt Me 209.

In the F-104, air passes through a heat exchanger submerged in water. The water cools the air for air conditioning in the cockpit before boiling off into steam. Greenamyer wanted to use a similar boil-off system in his Bearcat. Only instead of cooling air, he wanted to cool engine oil, just as the Me 209 had done. By bathing the oil cooler in a cold fluid, Greenamyer figured he could get rid of the two scoops in the airplane’s wings designed to provide cold air to the system. Eliminating the air scoops would reduce some aerodynamic inefficiency known as cooling drag.

Law immediately understood the concept of boil-off cooling, but he knew nothing about piston-engine aircraft. Luckily, Bruce Boland, a structural engineer he’d befriended on his first day at the Skunk Works, was a warbird fanatic. “He ate, slept, and dreamed old airplanes, especially Grummans,” Law says. “He was intimately familiar with them, and it was his lifelong dream to work on them. His hero airplane was the Bearcat.” The two formed a partnership.

Law engineered the boiler system, but instead of using water, he used ADI fluid—a 50-50 mix of water and methanol—because it cooled the oil to a lower temperature than water alone. (The unit reduced cooling drag so well that the resulting gain in airspeed was the equivalent of giving the engine an additional 200 horsepower.) Meanwhile, Boland upgraded the aerodynamic qualities of the airplane by slicking up the airframe. Flying the modified Bearcat, Greenamyer blitzed the Unlimited competition at Reno in 1965. And 1966. And 1967. And 1968. In August 1969, he flew the Bearcat to a world speed record of 483 mph. (The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale later re-calculated the speed to 482.464 mph, but the recalculation had no impact on the record.) A month later, he lapped the entire field at Reno. With nobody left to beat, Greenamyer told Law, “You and Bruce have to go off and start helping the other guys.”

His suggestion was not quite as altruistic as it sounds. Greenamyer knew that racers, fans, and, most important of all, sponsors would lose interest if the same guy won all the time. For the races to survive, they had to be competitive.

Greenamyer’s Bearcat was later enshrined in the National Air and Space Museum. Law and Boland became the Lennon and McCartney of the Unlimited air racing community. “Systems by Pete Law, Aerodynamics by Bruce Boland” was the legend painted on the fuselage of Strega, the nine-time Gold winning P-51 Mustang, but it could have been affixed to virtually every competitive entry at Reno. Red Baron, Dago Red, Dreadnought, Stiletto, Tsunami, Miss America, Rare Bear, Jeannie, Furias, Super Corsair, Mr. Awesome, Critical Mass—their fingerprints were on each of them. Boland died in 1995. “There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think of him,” Law says.

Wednesday, Day Three

Heat is the enemy of engines. The problem is especially acute at Reno because more power generates more heat. Back in the 1930s, aircraft engineers began cooling engines by injecting a mixture of water and methanol through a water regulator into the combustion chamber. This prevented a potentially catastrophic event—the detonation of the fuel-air mixture in each cylinder ahead of spark-plug ignition. Early, unwanted detonation, often accompanied by a death rattle known as engine knock, produces a spike in heat so extreme it can melt the aluminum on a piston. The cooling system enabled pilots to use more manifold pressure and more fuel in the air-fuel mixture that runs an engine; both translated into extra power. By the end of World War II, ADI systems were fitted to most high-performance fighters and bombers. These days, at Reno, all of the fast guys “go wet,” or run ADI.

Shortly after Law got involved in air racing, Greenamyer introduced him to Al DiMauro, the owner of Aircraft Carburetor in Burbank, California. “Al taught me everything there was to know about carburetors and water regulators,” Law says. He learned his lessons so well he began refurbishing and modifying units for DiMauro. And when DiMauro retired in 1978, Law essentially took over the part of the business that supplied the units for airplane and hydroplane racing. For an overhauled carburetor or water regulator, Law charges around $200. Law doesn’t do much hands-on carburetor work himself these days, but he remains a major supplier of ADI systems, based on water regulators that are nearly as old as he is. An ADI regulator can run as much as a grand, but, as Law told Sport Aviation editor Jack Cox in 1986, “When I sell a water-injection system, it’s warranted for life, effectively, and I come with the warranty.” At the races, his charges depend on the time he spends with a team to test and tune the cooling systems: anywhere from $50 to a couple hundred—enough, he says, to pay for his motel and meals while he’s there.

One of Law’s first customers was storied P-51 builder Dave Zeuschel, who sought his expertise in 1971. Unlike the air-cooled radial engine that Law had been working with in Greenamyer’s Bearcat, the Mustang was powered by a water-cooled V-12, so it needed an air inlet to cool the radiator. Law theorized that he could reduce the size of the scoop—and the consequent cooling drag—by spraying water into the face of the radiator. So he laboriously drilled dozens of tiny holes into quarter-inch stainless steel tubing and mounted this so-called spray bar in front of the radiator. Working with Zeuschel, he added deflector tabs and, later, injector nozzles to better atomize the water droplets. The spray bars were so effective that pretty much everybody copied them.

This year, Law has at least one of his cooling systems on 10 of the 11 fastest airplanes at Reno. And even if he hasn’t worked on a racer, he’s a resource. “If Pete’s got the time, he’ll answer any question,” says Mike Nixon, who built the Merlin engine powering Strega, which is the only top Unlimited that Law isn’t officially following. “He’s committed to the whole group, and everybody knows he won’t share your discovery without your permission.” Hence Law’s nickname in Unlimited circles: Secret Pete.

But despite all of Law’s efforts, at Reno, where engines are routinely run at twice the power anticipated by the original designers, things can still go wrong. Wednesday morning, when Law checks in with the 232 crew, Dale shows him a damaged piston that had been removed from the engine after Gibson’s 467.054 mph qualifying run.

“We’re officially out,” Dale says.

“Did he [engine builder Ray Anderson] have any comment about the little spot on the piston?” Law asks.

“He said, ‘Let’s have a biopsy, not an autopsy.’ ”

After Dale walks off, Gibson sidles up to Law. “I told them they were acting like a bunch of girls,” he confides. “We’re here to race, aren’t we?”

He’s joking, of course. If the engine failed in flight, the results would be not only outrageously expensive but also potentially fatal. Law has lost several friends in warbirds and has witnessed near catastrophes. He points to a woman walking through the pits: Karen Hinton. In 1979, her husband Steve was flying Red Baron, a Law-Boland collaboration that won two Unlimited Golds, when the Griffon engine quit. The last words Hinton radioed before auguring violently into the ground were, “Tell Karen I love her.” Hinton’s miraculous survival was widely attributed to a cockpit Boland had redesigned to maximize structural integrity.

“I get teary-eyed just thinking about it,” Law says. “Bruce and I almost quit after that. I’ve seen several people killed right in front of me. Back when we were doing stuff with Darryl, I got so nervous that I had to go to the doctor and get a prescription for Valium. I go on because I know people are going to keep on racing, and I do my best to keep them safe. I’m doing this to keep people alive.” Two days later, the air racing world would suffer the worst disaster in the history of the sport.

In Friday afternoon’s Gold heat race, Jimmy Leeward lost control of his formidable P-51 Mustang Galloping Ghost—which was flying faster than ever, thanks in part to Law’s ADI system. The airplane speared into the crowd. Leeward and 10 spectators were killed, and scores more were injured. Had it not been for the ADI fluid, which kept the ruptured gas tank from bursting into flames, the carnage would have been worse. Four lawsuits were filed against race organizers, and people wondered if there would ever be another race at Reno. Months later, the racing association announced that the 2012 event would proceed, but the organizers later had difficulty raising money for the insurance premium, which had jumped from $300,000 to $2 million.

But at the moment, the problem is getting 10 airplanes through the qualification trials.

Thursday, Day Four

With his son, Vance, chauffeuring him around the pits in the golf cart, Law makes the rounds. Miss America, a P-51 that has been racing since the 1960s, is his first stop; SteadFast his second, then Voodoo. “You doing okay?” he asks Voodoo crew chief Bill Kerchenfaut.

“It’s doing really good, and the data is clean,” Kerchenfaut says. “Now, we need a smart guy like you to tell us if everything is in the right place.”

“Remember, I’m not an aero guy.”

Kerchenfaut just shakes his head at Law’s customary humility. He likes to say that Law is the guy who “contaminated” him with a passion for air racing. He got involved with Law, Boland, and Greenamyer in 1968, when he was a sergeant at Edwards Air Force Base in California, and now, with 13 victories, he’s the winningest crew chief in Reno history. Yet to this day, Law remains his go-to resource for heating and cooling issues. “He was the senior thermodynamicist at the Skunk Works!” says Kerchenfaut, who, like the Gold racers he massages, runs constantly at redline. “That’s not a political position. They don’t give it to you just because. That’s big! Senior guy! The SR-71! The F-117! He can’t even talk about some of the stuff he did!”

The Bronze heat race is about to start. Law, anxious as a stage mother, asks Vance to park the golf cart as close as possible to the flight line. When the race begins, he carries on a running commentary about the action. “You’re a hell of an announcer, Pete,” a friend jokes. Soon, one of the two engines in Rod Lewis’ stunning Tigercat begins trailing smoke. After Lewis pulls out of the race, Law’s commentary changes, as if he’s talking Lewis down like a character in a cheesy airplane movie. “All right now, Rod. Stay calm. Stay calm. Stay calm. You can do it.” When the Tigercat lands safely, he cheers.

After the Bronze race, Rare Bear makes a quick test flight. When it’s back on the ramp, Law intently studies the airplane through his binoculars. “The exhaust pattern looks perfect,” he murmurs. But the big radial continues to pop and clatter while Dave Cornell and his crew check the magnetos. A spectator idly asks what kind of engine that is. “R-3350 Dash-91,” Law says without removing the binoculars from his eyes. “He’s not getting idle cutoff,” he adds, sounding worried.

His cell phone rings. “Hello, Dave Cornell,” Law says after answering it. “It’s still rich? It’s doing exactly the same thing?” Pause. “Huh.” Longer pause. “Did he see it derich?” Longest pause of all. “Jesus!” He hangs up and sighs. “That doesn’t sound good,” he says.

The days at Reno are long and demanding, but when the work is done, there are parties everywhere. Thursday night, Law and his wife, Joanne, attend a barbecue thrown by Rod Lewis. In the middle of the festivities, Rare Bear crewman Matt Thompson announces that there’s an award to be bestowed, and Law is stunned to discover that he’s the recipient. For all of his work “protecting” Rare Bear, he’s given a sheriff’s badge, and dozens of smaller “Deputy to Secret Pete” badges are distributed to the crowd. Law tears up as he stammers out a characteristically self-effacing acceptance speech. “I appreciate it very much, but I want to give you guys all the credit,” he says. It is, he acknowledges later, one of the high points of his career.

Another high point comes on Saturday, the day after the horror. Law is summoned by Unlimited class president Tom Camp to the lair of Grumman F4F Wildcat Air Biscuit. There, before about 200 people who have just been through one of the most harrowing days of their lives, Camp and Steve Hinton present Law with a trophy inscribed “Lifetime Member #1 Pete (Secret Pete) Law. Unlimited Division since 1965.” The most competitive people on the planet take a moment to say thanks to an engineer who cheers equally for them all.

Preston Lerner’s last article for Air & Space/Smithsonian, “Wingman in a Pontiac” (Apr./May 2012), was about U-2 landings.