The Airport Is Sinking

An engineering miracle is still no match for Mother Nature.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/0d/330d7396-5e36-4ed2-94e0-7fbf80bb4ebd/06c_jj2018_kansaisatelliteiss045_live.jpg)

This October, a new airport will open north of Istanbul, Turkey, on a foundation of muck from a former Black Sea marshland. In the Maldives archipelago, a sprawling expansion to its capital city airport is rising from the Indian Ocean. In 2020, a runway will open in an estuary of the Brisbane River in Australia, atop ground that engineers say is no more stable than toothpaste. Like dozens of airports already built on land reclaimed from water, those airports will sink. The only question is how fast.

The Kansai International Airport, serving the Japanese city of Osaka and occupying two artificial islands in Osaka Bay, leads the race to the bottom. Since it opened in 1994, Kansai has sunk 38 feet. Kansai’s islands were predicted to evenly settle, or as engineers say, subside, over a 50-year period before stabilizing at 13 feet above sea level. That’s the minimum elevation required to prevent flooding in case a breach develops in an encircling seawall. Portions of the first of the two islands created reached that threshold within six years. At least $150 million was spent to raise the seawall, but some engineers predict that by 2056, sections of the two artificial islands may sink 13 more feet—to sea level.

“When the Kansai airport was constructed, the amount of soil to reclaim the land was determined based on necessary ground level and subsidence estimation over 50 years after the construction,” says Yukako Handa, communications director for Kansai Airports, which manages Kansai’s two artificial islands as well as the original Osaka Itami airport on the mainland. Handa says that engineers simply couldn’t believe that there would be such a difference between laboratory estimates of the rate of consolidation—the process by which new layers of soil harden into a stable foundation—and the actual rate, once thousands of tons of fill had been deposited into the bay.

**********

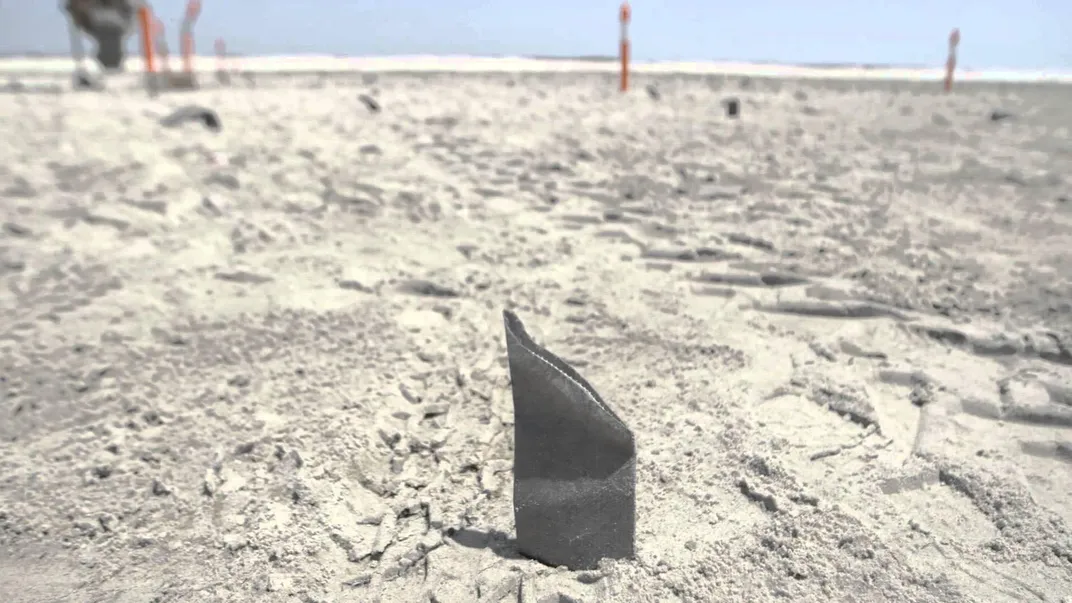

Reclaimed land is like a wet sponge. Before it can support the enormous weight of airport buildings, it must be transformed into a dry, dense foundation. To achieve this transformation, the Kansai construction crews laid sand five feet deep atop the clay seabed, then installed 2.2 million vertical pipes, each nearly 16 inches in diameter. After the pipes were pounded into the clay, they were filled with sand, which can absorb moisture from surrounding soil and from layers beneath. In other reclamation projects, fabric has been pushed into the pipes to soak up moisture, like a wick, or vertical drain. When the workers withdrew the pipes, the drains remained.

The next step was to load new soil on top of the sand layer. Construction engineers dredged soil from Osaka Bay, quarried more from nearby mountains, and even barged it in from China and Korea to build up layers. The mass of soil squeezes moisture into the less-dense sand or wicks. Layers below the new soil are dense and non-porous; the moisture in them can travel only horizontally, through capillary action, into the wick. Water then creeps upward to the surface to be drained or to evaporate, and as it leaves the soil, the layers consolidate to become stiffer and less likely to deform.

A seawall encircling Kansai was built to protect the area of operations. Made of 48,000 concrete blocks and rubble, the wall is anchored in steel chambers weighing hundreds of tons. As the dredging and filling continued, the added layers reached up to 65 feet above sea level.

At several stages of the work to heap new soil upon the seabed, operations paused to allow the new level to consolidate and sink. Once the layers stabilized at a height predicted to remain 13 feet above sea level for 50 years, 900 columns, resting on hydraulic jacks, were driven into the soil. The foundations for buildings rest on these columns, which can be adjusted by the jacks to offset variations in the rate of settling.

Work to create the islands of Kansai began in 1987. By 1990, when the first island had sunk 27 feet instead of the predicted 19, engineers became alarmed. To save the airport from the sea, workers excavated below the passenger terminal, inserted iron plates beneath the hydraulic jacks, and raised the columns in stages. Even with these corrective measures, the airport is likely to continue settling, perhaps for centuries, but at a far slower rate. Every two years, Kansai’s jacks will be readjusted if necessary. Each of the 900 columns has a meter the engineers can check for tilt.

Handa says there is no official estimated life calculated for Kansai. But Gholamreza Mesri, a professor of engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, predicts that island 2 could reach its warning point of 13 feet above sea level as early as 2023. If a typhoon strikes Kansai directly and waves slip over its sea wall, its runways and buildings will lie below water.

Beyond the rate of sinking, engineers are also concerned about its unevenness; different areas on the Kansai islands are sinking at different rates. In the center of Kansai’s passenger terminal—located on island 1—engineers measured a higher degree of sinking at the basement level than at the ends of the building. Workers coped with uneven sinking elsewhere by paving the airport runways with asphalt rather than concrete to minimize cracks or buckles.

Overall, the weight of hangars and parking garages has little effect on subsidence compared to the billions of pounds of force generated by the 69.5 square miles of fill forming the islands. Handa estimates that an Airbus A380 fully loaded with fuel and passengers weighs less than 0.0003 percent of the weight of the reclaimed soil.

**********

When Kansai opened in 1994, its cost was estimated at $8 billion, but by 2008 repairs and modifications had swelled the figure to $20 billion. Why risk such expense to build airports on reclaimed land?

When planning to build or expand an airport, cities or other entities—in Kansai’s case, Japan’s transport ministry—want to acquire land that is close to the city and its transportation links, land that is expensive and sought after for many lucrative uses. In analyzing the costs, they must factor in not only the cost of the land and construction but also the environmental toll of construction and the human toll of airliner noise, including the expense of relocating and compensating residents and affected industries. Against these costs, the builders weigh the airport’s role in the economy. Perhaps with a touch of engineering hubris, builders have determined that creating new land, close to a city center but offshore, away from populated areas, is less expensive in the long run than building airports where people live.

“Kansai was planned as a fundamental solution to the problem of the aircraft noise pollution surrounding the Osaka Itami International Airport,” says T. Furudoi of the Kansai International Land Development Company, which in 2006 managed the Kansai property. (The airport is currently managed by a consortium of private corporations led by Kansai Airports, which pays Japan’s transport ministry $350 million annually for operating rights.) As soon as the first jet landed at Itami in 1964, the residents of Osaka began protesting and filing lawsuits, and were eventually awarded compensation by Japan’s supreme court. For the Kansai airport, Ministry of Transport planners chose a site three miles offshore and situated it so that airliners would fly the entire arrival and departure pattern over unpopulated areas.

It has been expensive to keep Kansai International Airport high and dry, but the airport has done its job: to connect Osaka to the world. In 2016, more than 26 million passengers used Kansai, making it one of the 30 busiest airports in Asia. In 2001, the airport was honored by the American Society of Civil Engineers as one of the civil engineering monuments of the millennium.