Hurricane Walkaround

Aviation historian Ron Dick takes a closer look at an old warbird.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hurricane-631-mar08.jpg)

During his 38-year career with the Royal Air Force, Ron Dick flew 60 aircraft types and accumulated more than 5,000 flight hours. A contributing editor of Air & Space/Smithsonian, he now lectures and writes about aviation history. In December, Dick met with the magazine's editors at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, where he gave an engaging lecture about the Hawker Hurricane on display there, pointing out such features as the airplane's pneumatic braking system and its thick, old-fashioned wing design.

The restoration of the Hurricane (see Royal Air Force Museum, the Hurricane had spent time as an outdoor display at a Royal Air Force base in England, leading to extensive corrosion of the fighter's metal parts.

What also made the Hurricane restoration difficult was the airplane's elaborate structure, a confluence of aircraft construction techniques old and new that yielded a hybrid of wood, fabric, and shaped aluminum. With the unveiling of the Luftwaffe in 1934, Hawker chief designer Sydney Camm realized the urgent need to move the Royal Air Force's fighter fleet away from open-cockpit biplanes, such as the Hawker Fury, to faster, lower-drag monoplanes. "Camm had a decision to make," says Dick. " ‘Do I go for modern construction or do I, in the interest of time, use techniques that we've used for many years in the past?' And he decided that there would be a mix of the two, but they would lean pretty heavily on techniques they'd used for their biplanes."

Sure enough, though the Hurricane's wing leading edges are metal, the ailerons are fabric-covered. So is the rudder. The use of so much fabric, says Dick, was "extremely unusual for what was purportedly a modern frontline fighter aircraft. But fabric-covered parts were cheap to manufacture, and it was quick. So it saved time." (Camm was ever the pragmatist.) Manufactured early in 1944 at a factory outside London, the Museum's Hurricane, Royal Air Force serial number LF686, never saw combat. It did, however, serve as a training aircraft during the war before being reclassified as a maintenance training airframe used to train mechanics stationed at a Royal Air Force command in Chilbolton, Hampshire. In July 1948, the airplane was transferred to RAF Bridgenorth, where it went on display outdoors, opposite the guardroom.

Though it took more than a decade to rebuild the Museum's Hurricane, the restoration would have lasted even longer had the Garber team not gotten assistance from across the pond. In 1990, M.S. Bayliss, a British woodworking company, made the wood formers that shape the fuselage. Garber restoration specialist Bob McLean helped track down three missing components (two cockpit instruments and a landing light) in the United Kingdom, where they were removed from junkyard airframes and shipped Stateside. And lead Hurricane restorer Dave Peterson attended a Hurricane restoration seminar in Duxford, where, as the only American in attendance, he picked up invaluable knowledge from a group of British Hurricane owners.

Click on the photos above for a "walkaround" showing some of the Hurricane's finer points. Photos are numbered from left to right.

Main photo: A Hawker Hurricane Mark IIC is on permanent display at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia.

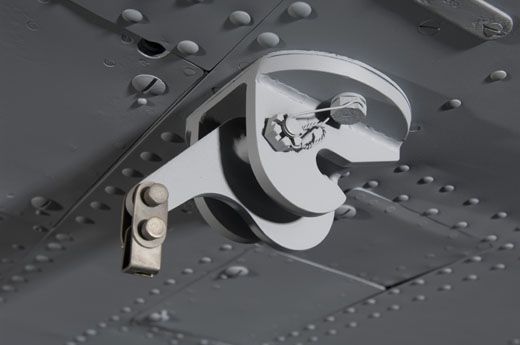

2. The main landing gear has a thin pneumatic brake line. Air traveling through the line would inflate a rubber bellows inside the wheel hub; the bellows actuated the brakes.

3. The Hurricane Mark IIC is powered by a Rolls-Royce XX engine, which can generate 1,280 horsepower, propelling the aircraft to a speed of 340 mph.

4. Though the Merlin XX's engine exhaust stubs face to the rear, earlier versions of the Merlin had exhaust stubs that stuck straight out—perpendicular--from the cowling. "When engineers curved the stubs and pointed them to the rear, they found that they got some jet propulsion," says Ron Dick. "And it added five to 10 miles an hour to the top speed of the airplane."

5. The Hurricane's big radiator created a lot of drag, but the structure was necessary to keep the liquid-cooled Merlin engine from overheating. Air entering the radiator's intake cooled the liquid (70 percent water, 30 percent glycol) cycling between the engine and radiator.

6. The Hurricane's thick wings created a lot of drag, but the thickness yielded at least one advantage. "This is an old-fashioned-type wing," says Ron Dick. "But it did something for the Hurricane's designers: It allowed them to place a lot of armament in the wings." In the case of the Mark IIC, two Hispano 20-mm cannons per wing.

7. Hard points underneath the wings enabled Mark IICs to carry 250-pound and 500-pound bombs, expanding the airplane's mission to that of fighter-bomber.

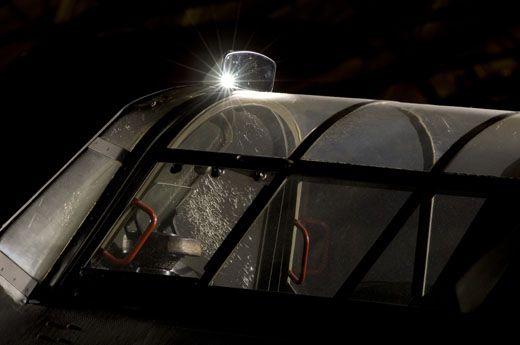

8. A mirror mounted at the forward canopy gave Hurricane pilots a view of action to the rear.

9. The rear third of the Hurricane fuselage is fashioned from fabric over a framework of wood and metal. "If you stand at the side of the Hurricane and look at it, you can see Sydney Camm's biplanes," says Ron Dick. "Because if you take a Hawker Fury from the early '30s—the beautiful biplane that they built—and take the top wing off, you'll see where the Hurricane came from. This section of the Hurricane, in particular, is almost identical [to the Fury biplane]."

10. On December 20, 2007, British aviation historian Ron Dick gave a lecture on the Hawker Hurricane at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.