Ike Learns to Fly

How Dwight D. Eisenhower got his ticket punched.

:focal(631x358:632x359)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/80/3980e9ee-5f52-4016-8dc3-b757fc938f26/04-2f_as2021_partofhistory-eisenhower_live.jpg)

Here is an enduring image of the Second World War—Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe, huddling with members of the 101st Airborne Division on the eve of D-Day. Later he watched as a procession of C-47s took off carrying numerous paratroopers, many of whom died later that night. Eisenhower and his companions saluted each plane. “It was a painfully moving and exhilarating experience,” his biographer Carlos D’Este wrote, “and the closest he would come to being one of them.”

In fact, Eisenhower did know a little of the terror and thrill of flight. Between 1935 and 1939, while serving as military adviser to the Philippine Commonwealth Government and assistant to General Douglas MacArthur, he helped create the first Philippine air force. And he fulfilled a lifelong dream, according to biographers—learning to fly.

It wasn’t easy. There were near-crashes as he learned to pilot a Stearman trainer. “Because I was learning to fly at the age of forty-six,” Eisenhower wrote, “my reflexes were slower than those of younger men.” Once, a sandbag jammed the control stick and Eisenhower had trouble landing the airplane. (“He made it down all right but he was disturbed and I don’t blame him,” his instructor Bill Lee said.) On a flight to Jolo, Lee pretended to take a nap, to test him. “Sheer panic crawled up and down my spine, shook my knees and, worst of all, paralyzed my tongue,” Eisenhower recalled.

One of his instructors was Jesus Villamor, the celebrated Filipino pilot. “I grew more and more irritated as I watched Eisenhower make mistakes time and again,” Villamor remembered. He thought Eisenhower was “a poor pilot but a good student.” (In 1957, Villamor wrote to tell Eisenhower how “that ‘poor pilot’ had made a great President.”) Another instructor said: “The biggest trouble I had with Colonel Eisenhower was eyesight. He was farsighted.” Despite setbacks, Eisenhower enjoyed himself. “I have a lot of fun—and even better than that—I think I furnish a lot of fun for the others out at the field,” he wrote.

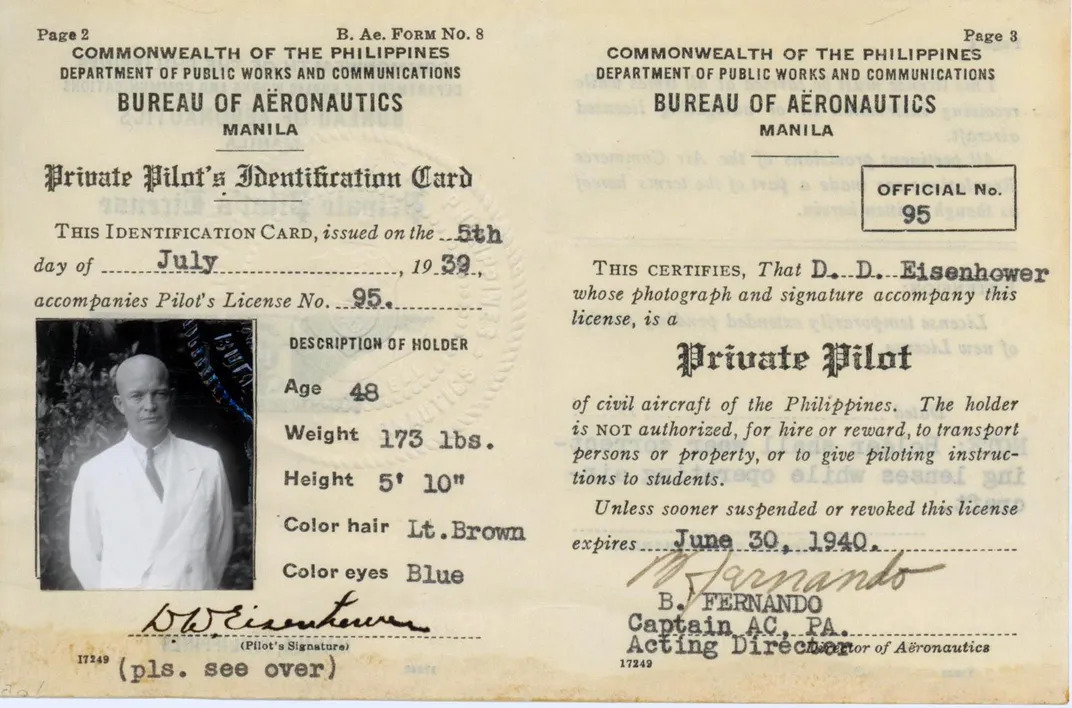

Eventually, Lee thought Eisenhower could fly solo. (“Off he went alone, circled, and landed several times. He was one happy fellow.”) And though it took him over two more years—much longer than younger trainees—to log enough hours and acquire a license “under both the American and Philippine bureaus,” he succeeded.

“So now I’m a licensed pilot,” Eisenhower wrote in his diary on July 20, 1939. “While I’ll never be good and after going to the States perhaps I’ll never get a chance to handle a stick—still I’ve realized one ambition.” Even though several biographies note that he earned only a private pilot’s license, in fact, the Philippine air force, after reviewing his credentials, awarded him its own pilot rating and wings in 1945.

But on that evening before D-Day, piloting was far from his thoughts, and the invasion order weighed heavily. A high casualty rate was expected among the paratroopers. “It’s very hard really to look a soldier in the eye,” he told his aide Kay Summersby, “when you fear you are sending him to his death.” After the last airplane left, she recalled how “General Eisenhower turned, shoulders sagging, the loneliest man in the world. Without a word, he walked slowly toward the car.”

Erwin R. Tiongson teaches economics at Georgetown University and writes occasionally about Philippine history.