In the Footsteps of the Mighty Eighth

A writer searches southern England for traces of a legendary World War II air force.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mighty_8th_631-mar07.jpg)

An American seeking the ghosts of the U.S. Army’s Eighth Air Force in eastern England can get lucky or get lost. I’d found my way to Rattlesden, a tiny village about 80 miles northeast of London, and I’d stopped at the Rattlesden post office and gotten fine directions to a nearby airfield. But within minutes of taking off in my rented car, I was lost. Miles later on a narrow farm lane, I asked the way of a man who’d pulled his car onto the grassy “verge” to let me pass. An abandoned U.S. Army Air Forces airfield? The B-17 base that launched 257 missions and lost 153 aircraft during World War II? Right-hand driver’s window to right-hand driver’s window, he set me straight. I soon went wrong.

The day before, I did find the well-preserved remnants of an Eighth Air Force base at Thorpe Abbotts. It’s between Eye and Diss, not far from Dickleburgh, though I’m not sure I could retrace my route. Fortunately, I’d called ahead and been briefed on the Dickleburgh bypass. The all-volunteer keepers of the Eighth Air Force’s 100th Bomb Group Memorial Museum at Thorpe Abbotts knew I was coming.

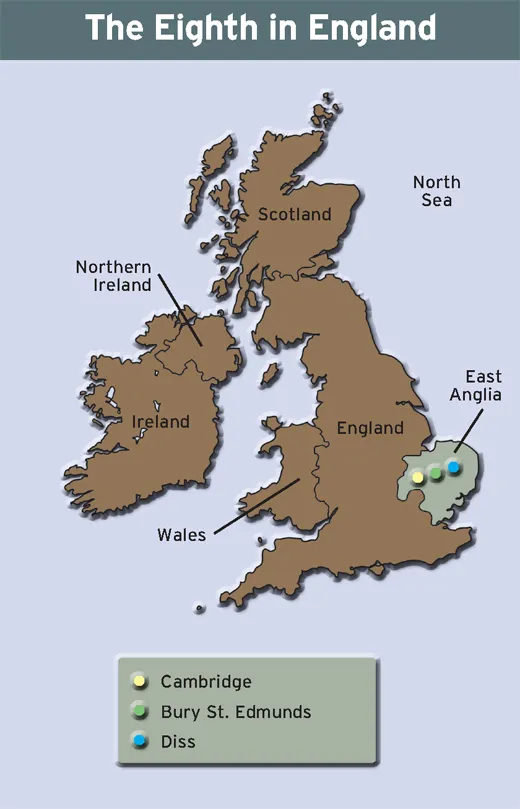

Rattlesden and Thorpe Abbotts are in Suffolk, one of five counties that make up the old Saxon kingdom of East Anglia, which juts into the North Sea. Flat, heavily agricultural, and perfectly placed for launching mass formations of propeller-driven, high-altitude heavy bombers deep into German territory, East Anglia was the cannon’s mouth for the U.S. Army’s Eighth Air Force. Sixty years on, it remains the heartland of the Eighth Air Force legend.

The U.S. military presence in the United Kingdom during World War II was immense. Between 1941 and 1945, three million U.S. servicemen and women flowed through Great Britain (with the Yanks taking 50,000 British war brides and a few war grooms in passing). By itself, the U.S. Army Air Forces contributed 500,000 personnel to this “friendly invasion,” with 350,000 of those in the Eighth Air Force alone. Compared with U.S. service personnel in other regions of England, the Eighth Air Force arrived earlier, stayed later, and settled more heavily in East Anglia. In 1944, one in seven residents of Suffolk County was American.

When I pulled up to the 100th Bomb Group Memorial, volunteers Ken Everett and Carol Batley were waiting at the far end. Batley was clutching the heavy metal lariat of keys that it takes to pass through the layers of padlocks, deadbolts, and alarm boxes that guard what remains of the Eighth at Thorpe Abbotts today. Gone are the concrete runways, hardstands, hangars, barracks, mess halls, bomb dumps, fire-fighting ponds, and, of course, big-tail Boeing B-17 bombers. What remains is the control tower, the quartermaster’s store, and a row of rescued and relocated Quonset huts (the British call them Nissen huts). In the old tower and its highly eclectic museum I began to feel what life must have been like for the young Americans who once lived here and for the English people who watched them fly off to battle every morning.

“I was 13 when they came in 1943, just the right age to be fascinated by it all,” says Everett, who points out the house just beyond the vanished perimeter fence where his family was living when the four squadrons of B-17s that made up the 100th Bomb Group began operations from Thorpe Abbotts. He vividly remembers standing outside and watching a shot-up B-17 fly by at rooftop height, popping flares, leaking fuel, and jettisoning gear as it swooped in for an emergency landing. Everett was delighted by the sound and spectacle. “At that age, you don’t appreciate the danger,” he says. Then one afternoon, while cycling home from school, Everett watched a B-17 sail across the road just in front of him, crashing about 300 yards away. Seven of the 10 aboard were killed. He also recalls the day a 100th Bomb Group gunner, standing outside his ball turret, accidentally set off the .50-caliber gun, spraying rounds at the village. “I have this recollection of hearing this sound—bing, bing, bing—overhead,” says Everett. “You weren’t aware that you were threatened until it was over.”

In 1977 Everett was one of the first volunteers that Mike Harvey, another local boy, lured into what seemed a hopeless mission to rescue the Thorpe Abbotts control tower. Harvey had been only seven in 1943, but he too had many memories of the U.S. air crews. Before his death in 1995, Harvey gave his energy and mad dreaming to preserving Thorpe Abbotts. The English farmers who took back their fields after the air station closed in 1945 stored straw for pigs in the derelict tower. The glass house on the tower roof had disappeared. Cracks and water damage were everywhere.

Demolition seemed most likely until Harvey approached the landowner with a plan to restore the tower as a museum commemorating the Eighth’s 100th Bomb Group. The owners gave Harvey a 99-year lease on the tower and a small footprint of land around it. (“We have to return the land in good condition when we finish,” says Everett.) Harvey rounded up other locals with good memories of the Yanks and those with no memories but lots of curiosity, like Ron and Carol Batley, post-war baby boomers. Ron was immediately taken with Harvey’s ideas, but Carol’s first reaction was “You must be crazy.” Then Harvey’s volunteers, including Carol’s husband and her children, descended on the Thorpe Abbotts tower with new glass, paint, and roof tar. Carol soon changed her mind: “If you can’t beat them, you had to join them. But you have to bear in mind that none of us had any experience in keeping a museum.”

Harvey knew that to get the museum going, he had to get the 100th Bomb Group veterans’ association on his side. In the late 1970s, he began cultivating Harry Crosby, the group’s former navigation officer, and Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal, by then quietly practicing law in the New York City suburbs. Rosenthal had volunteered for two tours with the 100th, flown a series of wrecks to safety, and been shot down twice, the last time over Berlin.

When Crosby and Rosenthal gave the thumbs-up to Harvey’s tower museum at Thorpe Abbotts, attics across the United States opened and out came a flood of artifacts. Rosenthal sent his dress uniform and his formidable array of medals. A bombardier sent the 35 bomb tags he signed for on his 35 missions, all mounted on a map of Germany. Then came flak jackets, a Norden bombsight, a never-opened GI shaving kit, the Boeing name plate off a pilot’s control wheel, a metal rooster “acquired” from a nearby pub, and the key to the 1141st Quartermaster Company’s storeroom at Thorpe Abbotts. Along with the memorabilia came more than 2,000 pictures, bundles of letters home, and a war’s-end telegram to the mother of a 100th Bomb Group POW: “The Secretary of War desires me to inform that your son S/Sgt Affleck, John W., has returned to Military Control.”

Museum volunteers dragged the old fire-fighting pond, recovering a bugle, a virtual market basket of 1940s consumer products (Ipana toothpaste, Brylcreem, Old Spice aftershave, little green Coke bottles), a horseshoe, and a copy of Fulton Sheen’s The Armor of God. The people around Thorpe Abbotts brought in bits and pieces from the 100th Bomb Group that had rained down on the land or were left behind in the outfit’s hasty departure. Locals came bearing U.S. Army-issue office furniture, telephones, tools, stepladders, bomb hoists, aircraft sheet metal, bent propellers, and a gas-attack rattle and all-clear bell complete with a sign warning, “These are not playthings.”

To me, the most amazing artifact was a well-worn Army-issue catcher’s mask that a homeward-bound GI gave to a local schoolboy at war’s end. Combat air crews who survived their mission tours were immediately sent home, but many of the enlisted men who came to Thorpe Abbotts in 1943 were still there in 1945. What’s an English schoolboy to do with an enlisted man’s catcher’s mask? Save it for 50 years, then return it to the Eighth Air Force.

There are at least a dozen other volunteer museums and memorial societies scattered across East Anglia; they too preserve U.S. Army Air Forces sites. Few associations are as active or as well organized as the 100th Bomb Group Memorial, though. Some don’t have towers to guard, and, like volunteer groups everywhere, their enthusiasm and activity ebb and flow. Most volunteer museums are open to visitors only one or two days a month, mostly on Sundays and mostly in summer. The Internet is invaluable in locating them, but luck helps. I got lucky the next day.

I went looking for Rougham, hoping for no more than a peek through the window of the museum there, which is dedicated to the Eighth Air Force’s 94th Bomb Group. My tourist map of old Eighth Air Force fields said that the museum is run by a Rougham Tower Association on an industrial estate just outside the town of Bury St. Edmunds. I spotted the exit for the Rougham Industrial Estate just in time and turned onto a street on which every vertical surface bore a poster announcing that today was the start of the two-day Rougham Airshow. The Rougham tower wasn’t just open, it was jumping. Inside, the association’s self-trained curator, Peter Langdon, gave me a tour of the sandblasted, patched, re-glazed, re-roofed, and repainted tower. Outside, the association chairman, Graham Crabtree, showed me how a proposed highway bypass would shave the corner of the historic zone around the Rougham tower.

The climax of the airshow would come the next day, I was told, when a flotilla of warbirds would descend on the Rougham airfield, including Spitfires, a Messerschmitt, a P-51, and a B-17 named Sally B. In the meantime, a World War II-era motor pool was already assembled on the field behind the control tower, ready for my inspection. I marched down a long line of parked U.S. jeeps, half-tons, staff cars, dispatch motorcycles, and an M24 tank. Elsewhere I saw vendors selling hot dogs, replica USAAF patches, model airplane kits, and Glenn Miller’s greatest hits. Straying beyond the day’s theme, other vendors were selling Thai noodles, classic car parts, contemporary war surplus, medieval replica swords, toy trains, helicopter rides, and two chances for £1.50 to ride an “unrideable bike.”

In the afternoon, the Rougham Tower Association would dedicate a new monument to the 94th Bomb Group, using an engine from a 94th B-17 that had spent the last 60 years underwater. In 1944 the engine belonged to Hello Mr. Maier, which had taken off from Rougham, attacked Munich, and ditched in the North Sea on the way back. The entire crew was rescued, but the engine didn’t turn up until 2000, when an English fishing boat snagged it from the bottom of the sea. Its years in the sand had half turned it to stone. The repainted engine and propeller had now been made into the centerpiece of the new monument thanks to the volunteers of the Rougham Tower Association, who have been working since 1993 to save the old control tower from ruin.

Relying on fundraisers, hard work, and a 99-year lease from the supportive landowner, the volunteers have restored the concrete tower’s wartime appearance, repainting the tower a very authentic Army green. The restoration evoked the days when the tower controlled the B-26 Marauders of the 322nd Bomb Group and then the heavy B-17s of the 94th. The volunteers forged ties with U.S. veterans, filling the new tower museum with donated artifacts. They redid the old radar repair shop as a meeting hall and filled restored Quonset huts with the larger Eighth Air Force artifacts that still surface in old barns and new construction sites: a bombardier’s seat, a bomb winch, and a large piece of Little Boy Blue, a B-17 that crashed near Rougham. The piece had been brought in by a man who said he’d been using it for decades to cover his lawnmower.

The Rougham Airshow had something on display last August even rarer than Brylcreem bottles—an Eighth Air Force combat veteran. Wilbur Richardson, a retired music and history teacher from Chino, California, was on hand for the memorial dedication, still able to fit into his USAAF sergeant’s uniform. Richardson first arrived at Rougham in early 1944, as the 21-year-old ball turret gunner on a B-17 named Kismet. He was about to start a 30-mission combat tour. Twenty-nine missions later, Richardson went to London on a 48-hour pass. “By the time I got back to Rougham,” he recalls, “they’d raised it to 35 missions.” On his 30th mission, Richardson was severely wounded by flak over Munich and shipped home.

Last summer, he was making his 15th return to Rougham, looking sharp enough for many more. But the ex-ball turret gunner’s appearance raised a question: What will happen to the Eighth Air Force legend as the flyboys fade away?

Legends are not always fair or even accurate. The U.S. Army deployed other air forces in Europe during World War II. There were two tactical air forces, the Ninth, which was based originally in England, and the Twelfth, which is better remembered as the desert air force after its start in North Africa. The Eighth was not even the only strategic air force. In 1943 the Fifteenth Air Force was set up in Italy to carry out the same kind of high-altitude, long-range strategic bombing that the Eighth was waging from England. These other U.S. Army Air Forces fought valiantly, but the Eighth turned out to be the one that flew into legend.

On these and other issues, the American Air Museum in England is a useful corrective. And it’s not hard to find. It’s at Duxford, just off the M11, between London and Cambridge. The American Air Museum is actually part of the Imperial War Museum, the British equivalent of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Inside, I sought the iconic aircraft of the U.S. Army Air Forces. The American Air Museum covers the full range of U.S. flying in Europe, from a SPAD XIII in Eddie Rickenbacker’s 94th Aero Squadron colors to a recently retired SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft. But the knots of visitors are always thickest by the signature airplanes of the Eighth Air Force—a green-painted B-17G named Mary Alice and a bare metal B-24M Liberator named Dugan. Hanging from the ceiling was a P-51D Mustang painted with the checkered nose markings of the 78th Fighter Group. I studied a photo of 78th pilots lounging outside the group briefing room, waiting in the late afternoon sun at Duxford to see who didn’t make it home from the day’s mission. I turned from the photo to look out on the Duxford main runway beyond the glass. They waited just out there.

England is knee deep in history, and wading through it in a search for the Eighth Air Force can take you to unexpected depths. It can lead to All Saints’ Church, in the village of Carleton Rode, which has a glorious stained-glass window commemorating 17 U.S. airmen killed when their two B-24s collided overhead in November 1944. It can lead to pubs like The Swan in Lavenham, where crews from the 487th Bomb Group signed the walls. Sixty years later, the signatures are still there, safe under glass. (The Swan is now part of a swank hotel, its staff and patrons too young to remember the pub’s wartime customers.) Everywhere I went, there was the East Anglia summer sky, a turbulent kaleidoscope of sudden blue, sudden cloud, and sudden squalls.

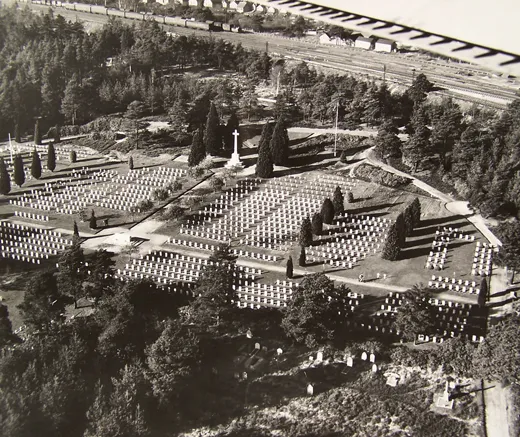

The rain lifted for the short drive north from Duxford to Cambridge. I exited the highway just west of the university city, into the leafy suburb of Madingley, where I was bound for the Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial, the resting place for 3,812 American servicemen and -women (along with a scattering of U.S. War Department employees, Red Cross workers, Merchant Marine sailors, and one war correspondent) whose bodies were recovered in the United Kingdom during World War II. Another 5,126 are listed on the Wall of the Missing.

The American Cemetery is operated by the U.S. government’s smallest independent overseas agency, the American Battle Monuments Commission. By law, the cemetery’s superintendent and his assistant are American, but the other staffers are local, including cemetery associate Arthur Brookes. No one knows more about the dead and the missing honored at Cambridge than Brookes does. He knows where to find bandleader Glenn Miller on the Wall of the Missing, listed as Major Alton G. Miller, USAAF Band. There is the name of John F. Kennedy’s elder brother, Lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy, cut in stone among the U.S. Navy missing. Buried here are 17 women, 32 civilians, and someone from every state in the Union, plus the Panama Canal Zone and Puerto Rico. Twenty-four of the burials are unknown.

Brookes says that the American Battle Monuments Commission D-Day cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer in Normandy draws the most visitors—three million a year—but the American Cemetery at Cambridge, which is the only U.S. World War II cemetery in the United Kingdom, still gets 150,000 visitors a year. Roughly 70 percent of the burials drew from the U.S. Army Air Forces, and most of those came from the Eighth Air Force. On the memorial for the missing, however, the percentage of Eighth members is much higher: It was in the nature of the Eighth’s long-distance bombing campaign, says Brookes, that many fell unseen into remote country, coastal waters, or their burning targets below. By war’s end, more than 10,000 Americans had been buried here. In 1945, the U.S. government offered the next of kin of deceased overseas personnel the option of repatriation; about 60 percent accepted.

Yet the buried and the missing at Cambridge represent only a fraction of the Eighth’s 26,000 dead. Approximately 135,000 Eighth personnel flew combat missions. That means an Eighth air crew member had roughly a one-in-five chance of dying. Factor in another 29,500 air crewmen who were shot down, ending up as POWs and internees. Suddenly, the scale of the Eighth’s sacrifice becomes terribly clear.

I walked on, following the curved rows of graves; it is a beautiful place. The design is American—both the architects and the landscape architects were from Boston—but the velvet grass and lush rose gardens are the work of the English climate and English gardeners.

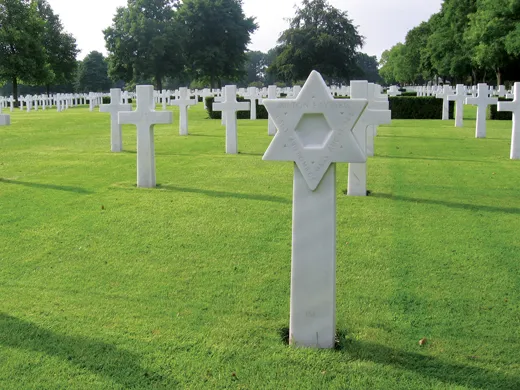

The cemetery is laid out in a great quarter-circle, almost like the shape described by the hands of a clock reading three o’clock. Along the hour hand runs the Wall of the Missing, the names cut in Portland sandstone. Along the minute hand runs an avenue of trees. The rows of graves sweep in arcs between them. The white marble crosses and stars of David are washed every month. When the inscriptions become weathered, the stones are replaced.

The combat air crew buried here are those who came home mortally wounded, crashed on English soil, or whose bodies were recovered from the sea. Here also lie Eighth Air Force ordnance handlers killed in bomb-loading accidents. Here too are the Eighth’s postal clerks, company bakers, and Women’s Army Corps members, dead of infections, car crashes, V-bombs, and natural causes. The headstones make no distinctions.

I had brought, from the museum at Thorpe Abbotts, the name of Sergeant George J. Brassell, 418th Bomb Squadron, 10th Bomb Group, who is buried in Section F, Row 3, Grave 108. His airplane, a flak-damaged B-17 named Dorhelcia, went down in the North Sea on December 22, 1943. Brassell’s body was the only one to wash ashore. The other nine crew members are remembered on the Wall of the Missing.

Brookes told me that when family members visit or request a photo of the stone, the staff presses wet sand gathered from Omaha Beach in Normandy into the inscription to make visible the name, rank, unit, date of death, and home state. The harmless sand is left in place. The rain carries it softly away.