Letters from a Science Fiction Giant

Exploring the riches of the Arthur C. Clarke Collection at the National Air and Space Museum.

:focal(822x2630:823x2631)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/6c/aa6cf5cf-360f-4144-96e7-6c12010cebff/16g_jj2018_nasm-9a12591-a_live.jpg)

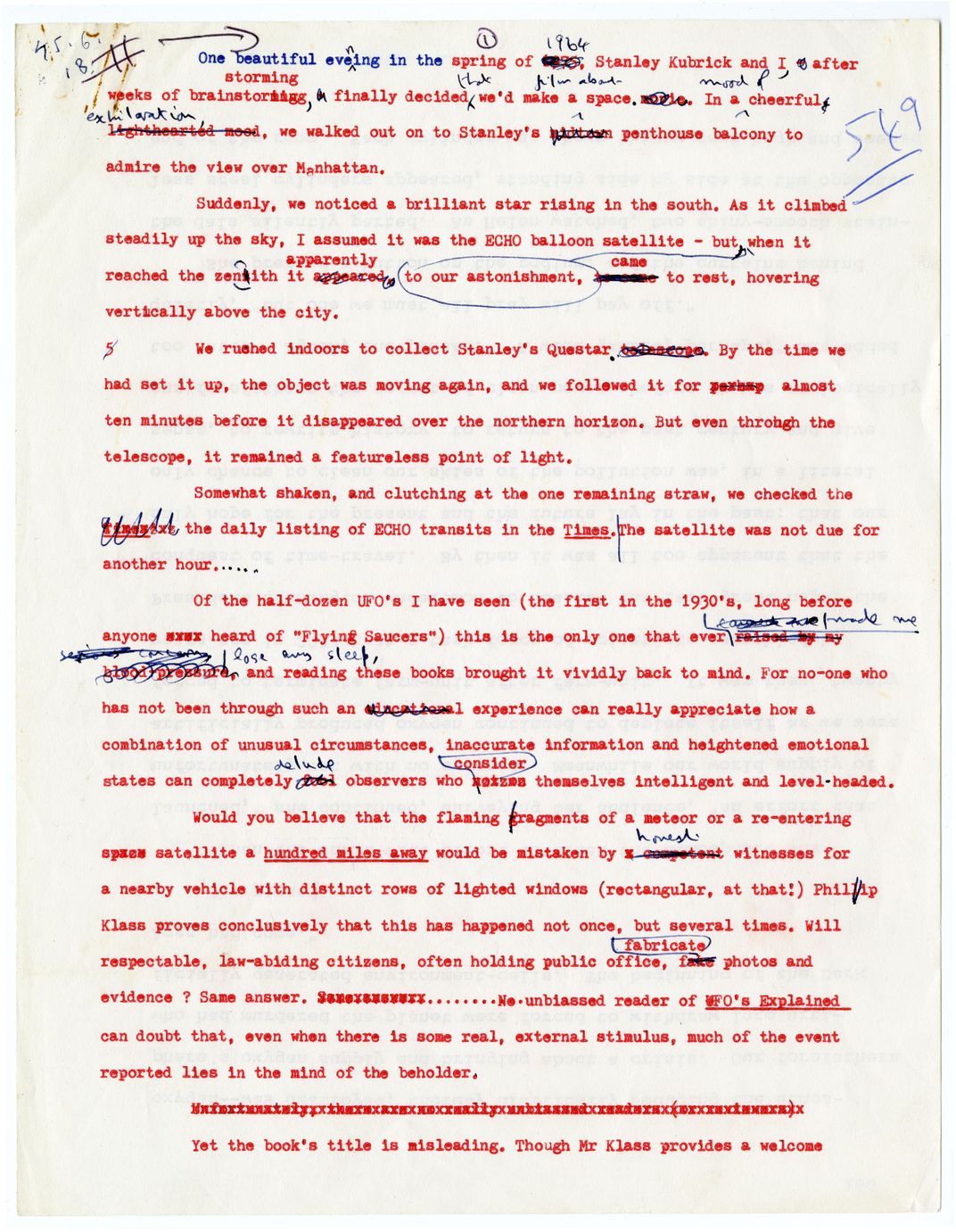

He claimed he could barely recall his childhood, but Arthur C. Clarke vividly remembered the day in November 1928 when he saw his first issue of the science fiction pulp magazine Amazing Stories. “A spaceship looking like a farm silo with picture windows is disgorging its exuberant passengers on a tropical beach, above which floats the orange ball of Jupiter, filling half the sky,” he recalled for the New York Times decades later. The magazine was for sale at the local Woolworth’s, and the 12-year-old Clarke would soon be spending his school lunch hours hunkered in the aisle, avidly consuming science fiction.

Six years later, the precocious teenager joined the British Interplanetary Society, where he soon became treasurer. “My main interests are astronomy and astronautics,” he wrote in a 1937 letter to science fiction author Sam Youd, best known for his young adult series The Tripods. “I am certainly fond of arguments, and usually have one or two on my hands. They are great fun, and often useful. Anything from music to astronomy and back to wave mechanics via politics is welcome. But not sport!”

The letter is one of thousands of items in the Arthur C. Clarke Collection, in the National Air and Space Museum archives. The collection—all 188 boxes—arrived at the Museum in 2014 and has been pored over by curators and researchers ever since, but especially this year, the 50th anniversary of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The collection includes letters from the 1930s to the 2000s, Clarke’s diaries and address books, photo albums, and manuscripts and page proofs from nearly all of his works.

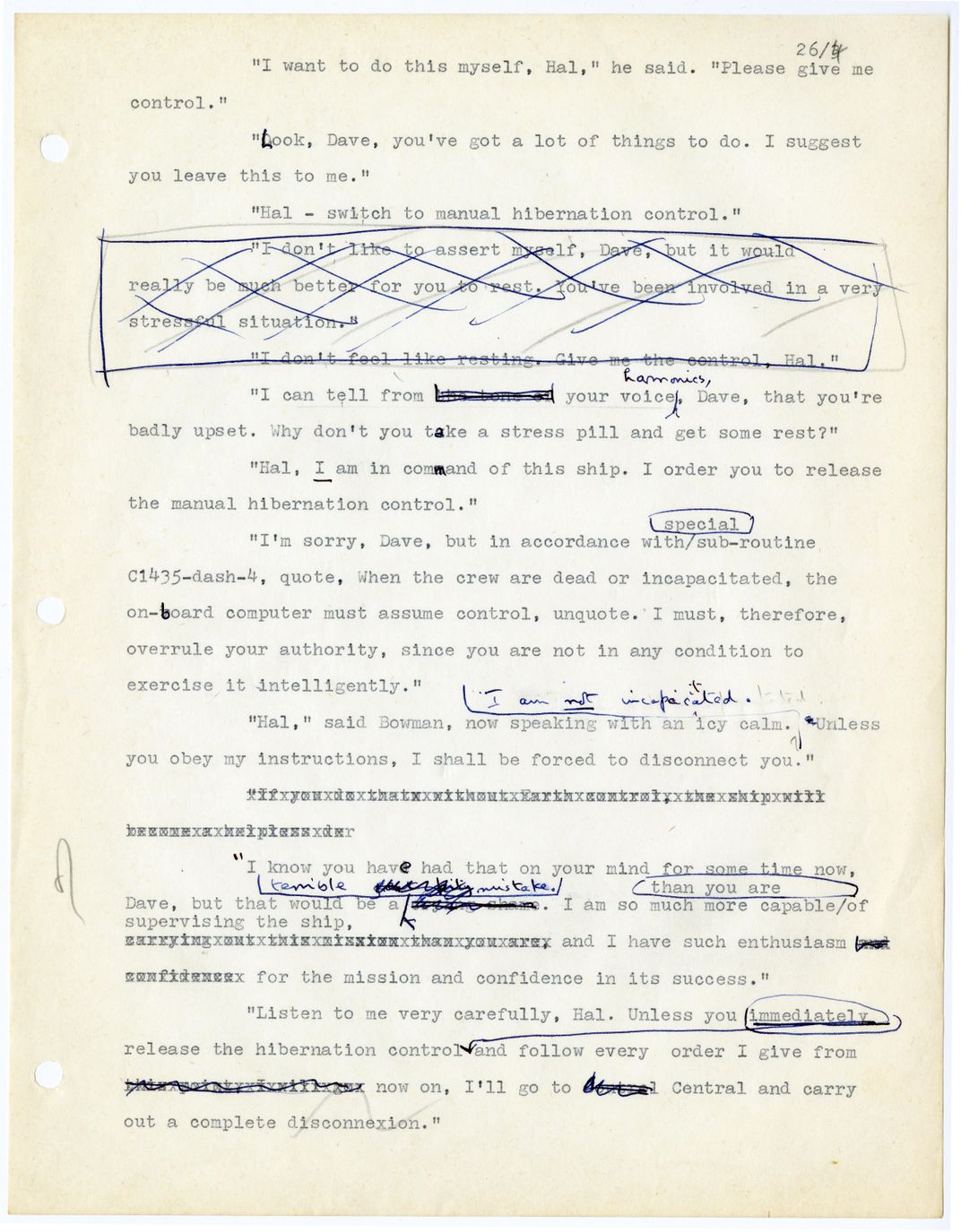

“One of the strengths of the collection is Clarke’s manuscripts,” says curator Martin Collins. “Clarke had working notes as he prepared things for publication. It really highlights his deep belief and attention to making his fictional stuff as close to scientific fact as he could.”

The majority of the correspondence dates from the 1960s on. Tucked inside one folder, a letter from Wernher von Braun cordially invites Clarke to the October 11, 1968 launch of Apollo 7. “The rocket will carry [Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele, and Walter Cunningham] on a ten day earth orbital flight,” writes von Braun. “This mission will demonstrate the performance of the Saturn IB launch vehicle, the spacecraft’s command and service modules, and the crew and support facilities.” (Von Braun helpfully attached a list of motels in the Cape Kennedy area, which ranged in price from $5 to $18 a night.) A year later, Clarke, at Walter Cronkite’s side, covered the Apollo 11 mission for CBS.

Surprisingly, there isn’t much correspondence between Clarke and 2001 director Stanley Kubrick. Collins has a theory about that: “Clarke was a very generous person,” he says. “He had a habit of sharing his papers and lending things out, and it’s quite possible that people never sent them back.”

The collection also includes information on Clarke’s role in the development of communication satellites. In 1945, Clarke published a paper in Wireless World suggesting a way in which satellites placed in geostationary orbit could provide a near-global communications capability. This paper, says Collins, “is cited by many people in the satellite community as a critical intellectual jumping-off point, and Clarke was recognized for this many times.” Clarke lectured on the topic throughout his career, often joking that the concept did not bring him material gain. In a 1958 letter he wrote, “Have been asked to give a talk to the American Association here. Will talk about the communications satellite under the title How I Lost Ten Million Dollars In My Spare Time.”

The Museum also holds research conducted by Clarke’s biographer, Neil McAleer, a collection that includes photographs and correspondence with Clarke. According to archivist Patti Williams, “McAleer interviewed a number of people while writing the biography, and that research wonderfully complements the Clarke collection.”

After the writer’s death in 2008, the Arthur C. Clarke Trust considered turning his home in Colombo, Sri Lanka, into a museum. Under that scenario, all of Clarke’s papers would have remained there. But in 2011, the trust approached the Smithsonian to see if the institution would be interested in acquiring Clarke’s collection. After three years of negotiations, Collins and Williams traveled to Sri Lanka (where Clarke had lived since 1956) to package the papers for transfer to the United States.