In the Museum: Fashion Lighter Than Air

In the Museum: Fashion Lighter Than Air

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arch_NASM_Main_JJ09.jpg)

The invention of the balloon struck the men and women of the late 18th century like a thunderbolt. In the fall and winter of 1783, Parisians gathered in unprecedented numbers to watch fellow human beings venture off the earth for the first time. On December 1, 1783, as many as 400,000 people—half the city’s population—swarmed into the area around the Château des Tuileries to watch a hydrogen balloon carry J.A.-C. Charles and M.N. Robert into the heavens. Guards struggled to restrain the crush of citizens clogging the narrow streets, alleyways, and garden paths leading to the launch area. In search of good vantage points, people scrambled up lampposts and onto walls, clambered over fences, and climbed out windows onto roofs.

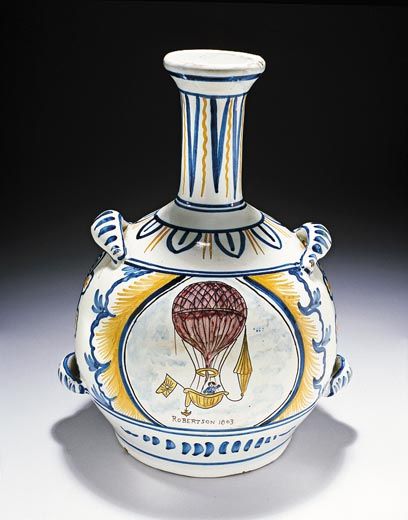

Across Europe, people were overcome with balloon mania. Parisians sipped Crème de l’Aérostatique liqueur and danced the Contredanse de Gonesse in honor of the village where Charles and Robert returned safely to earth. Balloons inspired hats, hair and clothing styles, jewelry, snuffboxes, wallpaper, chandeliers, birdcages, fans, clocks, furniture, tableware, and more.

A world-class collection of late 18th century consumer goods commemorating the birth of the Air Age is on view at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia. Visitors can see a set of balloon-back chairs with embroidered seats illustrating the great events of early balloon history, as well as chests of drawers, dressing tables, and writing desks with intricate wood inlays depicting the launch and landing of the first aeronauts.

U.S. citizens heard about the new field of aeronautics from American diplomats living in Paris who were caught up in the excitement. “All the Conversation here at present turns upon the Balloons…and the means of managing them, so as to give men the Advantage of Flying,” Benjamin Franklin wrote. One of his associates commented that among “all our circle of friends, at all our meals, in the antechambers of our lovely women, as in the academic schools, all one hears is talk of experiments, atmospheric air, inflammable gas, flying cars, journeys in the sky.”

Franklin reported that small balloons made of scraped animal intestines were being sold “everyday in every quarter.” His grandson, William Temple Franklin, released one of these little gas bags in his bedroom, where it “went up to the ceiling and remained rolling around there for some time.” Grandfather Benjamin emptied the membrane of hydrogen and forwarded it to English friends, along with instructions for generating hydrogen to fill it. That winter, Franklin visited a friend’s home for “tea and balloons,” and attended a fête at which the duc de Chartres distributed “little phaloid balloonlets” to his guests. At another memorable entertainment, staged by the duc de Crillon, the aging diplomat witnessed the launch of a hydrogen balloon some five feet in diameter that kept a lantern aloft for more than 11 hours.

Sixteen-year-old John Quincy Adams, one of the youngest members of the American diplomatic community in Paris, also mentioned the small balloons that street venders were selling. “The flying globes are still very much in vogue,” he wrote on September 22, 1783. “They have advertised a small one of eight inches in diameter at 6 livres apiece without air [hydrogen] and 8 livres with it.... [S]everal accidents have happened to persons who have attempted to make inflammable air [hydrogen], which is a dangerous operation, so that the government has prohibited them.”

Why the excitement? For many, the colorful balloons rising over the rooftops of Paris symbolized a new era in which science and technology would effect startling change. The balloon was proof that a deeper understanding of nature could produce what looked very much like a miracle. What else was one to think of a contrivance that would carry people into the sky?

And if men and women could break the chains of gravity, could they not also cast off the shackles of tyranny? Across the Atlantic, Americans were demonstrating that ordinary citizens were perfectly able to govern themselves without the assistance of a king. Among the people of France and England, discontent was bubbling away just beneath the surface. The balloon seemed to be the harbinger of a liberating new age.

The balloon-related objects filling several large cases at the Udvar-Hazy Center are some of the Museum’s oldest items. They are reminders of a time when flight was new and the sight of human beings flying through the air still seemed nothing short of miraculous.