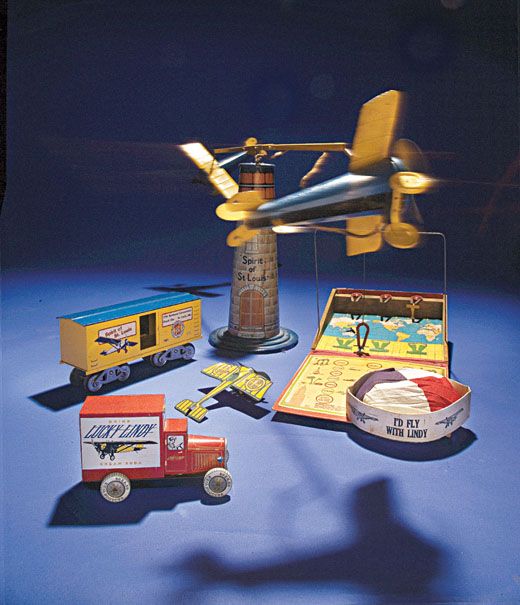

Lindbergh for Sale

Stanley King’s memorabilia collection.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/4c/1c4c5a00-3f8d-4290-8ea3-05d270d700fe/lindbergh-388-sept06jpg__800x600_q85_crop.jpg)

Stanley King started with buttons. An artist, musician, and founder of a lucrative fabric-design business in New York City, King has had the financial wherewithal to buy thousands of pieces of memorabilia relating to some of his favorite subjects: George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, American jazz, and, perhaps most passionately, Charles Lindbergh. In 2002, King donated his vast collection of Lindbergh memorabilia to the National Air and Space Museum, and on June 20, nearly 400 of the artifacts went on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia.

Born two years after Lindbergh’s 1927 New York-to-Paris solo flight, King, as a child, became fascinated by Lindbergh. “Here was a young man who changed the world,” he says. Later, a 20-something King bought his first chunk of Lindbergh memorabilia. “There was a little hobby store in Manhattan that I walked into, and they had a bunch of stuff from Lindbergh’s 1927 welcome to New York,” he says. He happily paid 25 cents apiece for dozens of buttons and ribbons, but that was just the beginning. Lindbergh, flying the Spirit of St. Louis, had toured the 48 states following his return to New York, and at every stop, souvenirs were for sale. King soon discovered that Lindbergh had spawned a merchandising bonanza. “There was china,” he says. “And the next thing, it’s curtain fabric and drapery and tapestry and clothing and pillowcases. And quilting. And I’m saying ‘This is unbelievable.’ ”

King says that during the 50-plus years he has collected all things Lindbergh, he has spent about $200,000. “I’ve never been shy with something,” he says. “If somebody said, ‘This is $500,’ that was it. I wanted it, and I thought it was important. But I started collecting when those buttons were 25 cents, and then the market moved along. I mean there are things I’ve paid 10 and 20 thousand dollars for. There’s one group of telegrams that were bought from the estate of his lawyer. All the congratulatory telegrams” that were sent after Lindbergh’s transatlantic triumph. To find these treasures, King patronized such auction houses as Christie’s and Sotheby’s, and he regularly peruses the goods available from the online auction house eBay, where he bought a toy Spirit of St. Louis glider, the only example he’s ever seen.

Before King sold his textile business in 2003, he lived and worked on an entire story of a building on Fifth Avenue. Half of the space was a studio for King’s staff, and the other half was a cavernous apartment dominated by the Lindbergh collection. “I must have had 20 Spirit of St. Louis’s hanging from the ceiling,” says King. “And volumes of memorabilia” displayed on lighted shelves. “I had weather vanes from farms that were done like the Spirit of St. Louis. Imagine people coming up and just absolutely flipping out. And then I’d serve them lunch as well.”

As much as King enjoyed living in a virtual museum, he started wondering what he should do with all the Lindbergh stuff. His children didn’t want the collection, and King had no desire to sell it. “I said I should give it to some place that it could be shared with a lot of people,” he says. His first choice was the Museum, since that is where Lindbergh’s airplane is displayed, and aeronautics curator Dom Pisano was delighted to accept. The King collection has 800 major objects and thousands of smaller pieces, including sheet music, menus from banquets Lindbergh attended, and photographs.

Museum specialist Carl Bobrow has spent more than a year cataloging each Lindbergh item. Much of the King collection is now viewable online. “To work with Lindbergh items is just a treat,” says Bobrow. In fact, he has been inspired to write a book documenting the King collection as well as other Lindbergh artifacts.

As for King, he looks forward to making the trip from New York to see his collection on display. He won’t come empty-handed: “I must have another 20 items to bring down,” he says.