Jim Lovell, From Carriers to the Moon

The veteran astronaut is honored with the National Air and Space Museum Lifetime Achievement trophy.

:focal(1155x804:1156x805)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0d/1b/0d1b3c8a-83a2-4bc2-b855-662c7385aaae/16g_am2016_lovell-james09_live.jpg)

James Lovell may be best known as the commander of Apollo 13. During that April 1970 mission, the service module’s cryogenic oxygen system failed, putting the astronauts’ lives in danger. For four tense days, he and crewmates John Swigert and Fred Haise, along with NASA ground controllers, worked to return their spacecraft safely to Earth.

But Lovell, the 2016 recipient of the National Air and Space Museum’s trophy for Lifetime Achievement, is being honored for the many accomplishments during his career—which started early.

“I was interested in rockets and astronomy long before the Glenns and the Shepards of the world could spell rocket,” Lovell joked in a 1999 oral history recorded at NASA. “I was interested in it way back in high school.”

The Milwaukee boy who avidly read Jules Verne novels as a child was, by the mid-1940s, in high school and building his own rockets: He would stuff mailing tubes with gunpowder and glue, then launch them from a nearby field.

Watching nervously across the street was Marilyn Gerlach, Lovell’s future wife. (They’d met in the school cafeteria lunch line, flirting shyly over meat loaf and succotash.)

“I wanted to become a rocket engineer,” recalled Lovell in 1999. When the obsessed teen wrote to the American Rocket Society asking for advice, the organization suggested he attend either MIT or Caltech. Unable to afford the tuition, Lovell took an ROTC scholarship at the University of Wisconsin. After two years he transferred to the Naval Academy. He hoped to become a pilot, his choice after rocket engineer.

Three and a half hours after Lovell graduated from the academy, he and Gerlach married. Lovell immediately headed to flight school.

By 1953 Lovell was dispatched to Moffett Field in California and assigned to Composite Squadron Three, an aircraft carrier group. Six months later he made his first nighttime carrier landing, off the coast of Japan. Lovell recalled in 1999 his response to the assignment: “I told the skipper, ‘You know, I’m having a little trouble flying in the daytime yet, and you want me to go out at night?’ ” Flying a F2H Banshee, Lovell searched for the USS Shangri-La. It was slightly more challenging than he’d expected: He was using a light he’d invented to illuminate his knee board, and it accidentally short-circuited his instrument panel, so Lovell had to locate the carrier by the trails of phosphorescent algae churned up in the carrier’s wake. A master of understatement, Lovell would recall the event years later: “It was a great experience, and I learned an awful lot.” (The memory became a famous scene in Apollo 13. In the film, Tom Hanks recalls the fear of not being able to find the carrier in all that blackness, a foreshadowing of the possibility of not making it home to Earth.)

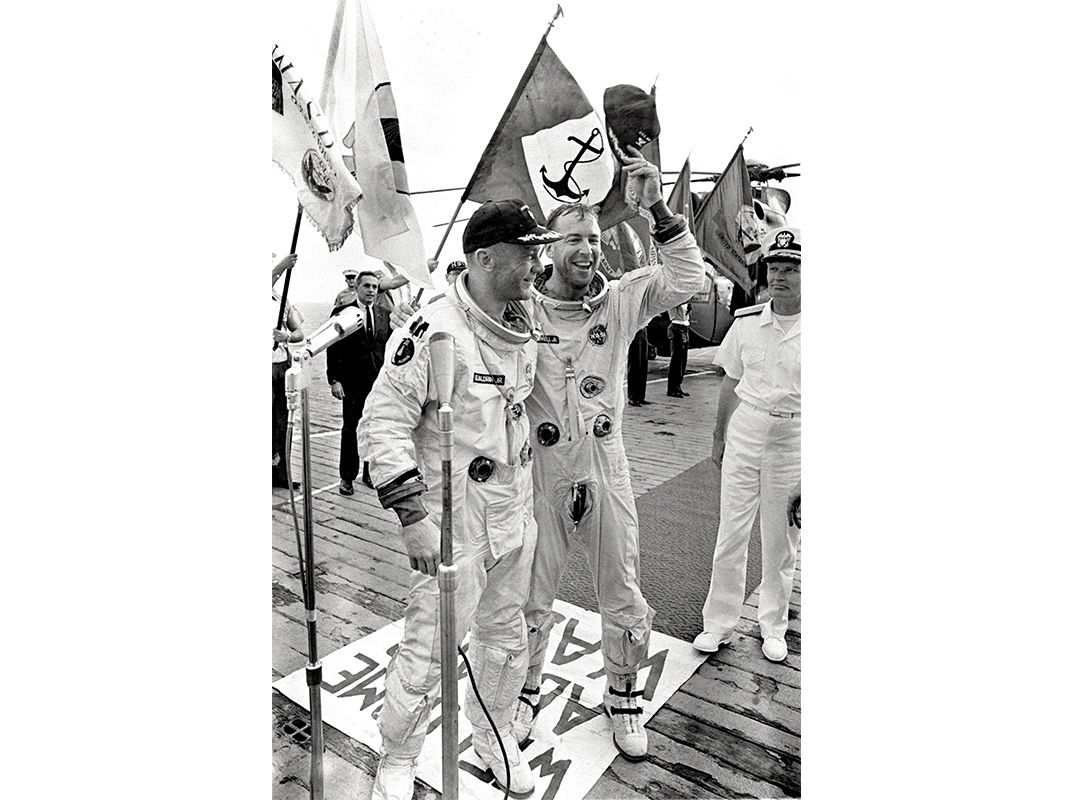

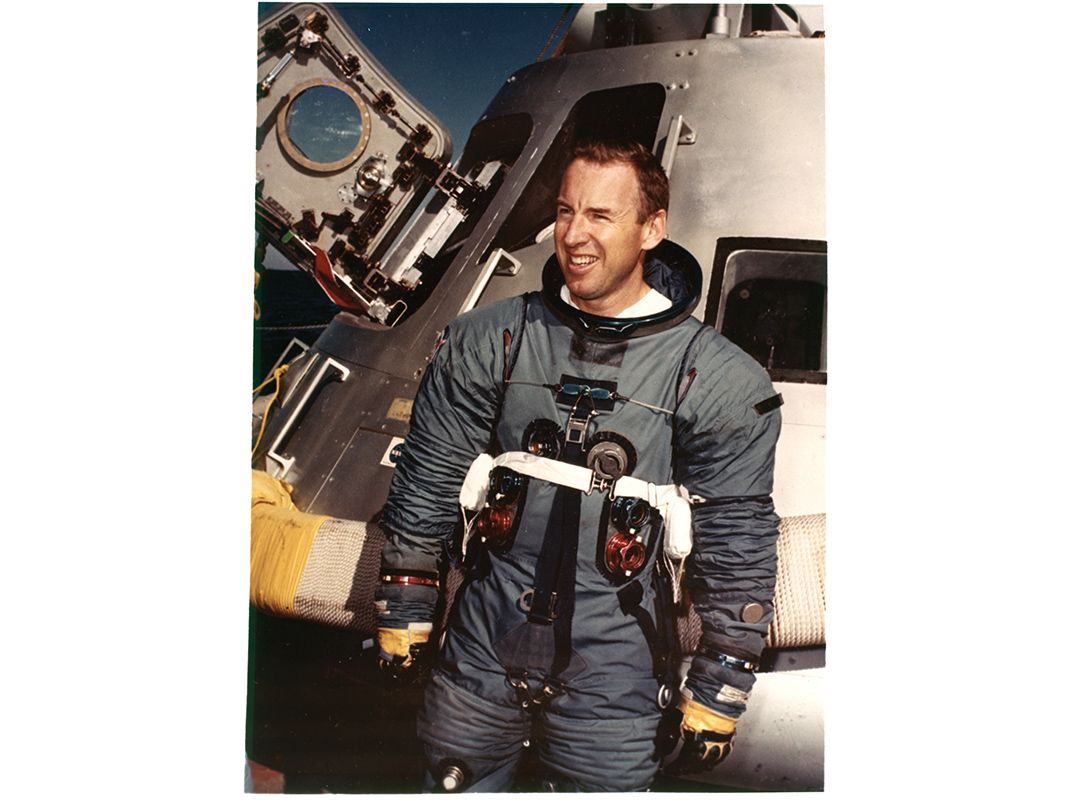

Lovell would eventually make 107 carrier landings, and go on to teach plebes how to fly the FJ-4 Fury, the F8U Crusader, and the F3H Demon. Then he headed to the naval base at Patuxent River, Maryland, to become a test pilot. His experience as a naval aviator and test pilot got him into NASA’s second group of astronaut trainees—for the Gemini missions—in 1962. (A minor medical condition kept him from being one of the original Mercury 7.) Over the next 11 years he would spend a total of 715 hours in space, a record not surpassed until Skylab.

Many artifacts from Lovell’s space career are in the Museum’s collection. Visitors can see the small, battered Gemini 7 capsule in which Lovell and Frank Borman orbited Earth for 14 days in 1965, demonstrating that humans can live in weightlessness. Back then, NASA, worried about leaks in the spacecraft, required astronauts to wear spacesuits at all times. In his oral history, Lovell recalled the suits as hot and bulky. While Borman waited in vain for NASA to give him permission to remove his suit, Lovell shucked his, causing his young son to later exclaim, “My Dad orbited the Earth in his underwear!” Borman and Lovell—who ended up sharing a toothbrush on the mission—remain good friends. In 1999, Borman said, “Jim Lovell was a wonderful guy to spend 14 days with in a very small place.”

In 1966, Lovell commanded Gemini 12, the 10th and final manned flight of the program, which helped demonstrate that an astronaut could safely work outside the spacecraft. Visitors can see many items from that mission, including the hatch-closing lanyard Buzz Aldrin used on his three spacewalks.

Lovell’s next mission was Apollo 8, which some—including Lovell—argue was NASA’s finest moment. “We saw the far side of the Moon, which no one had ever seen before,” Lovell recalled. “That was the high point of my career. I think it was the high point of NASA’s career, too.” The collection contains more than 70 items relating to the six-day spaceflight, of which Lovell was command module pilot and navigator.

As spacecraft commander of Apollo 13, Lovell became the first man to journey to the moon twice. Some 140 hours into the stress-filled mission, his amiable nature remained intact: Although sleep-deprived, cold, and weary, Lovell was still able to quip to ground control, “Well, I can’t say that this thing hasn’t been filled with excitement.”

Lovell was given the Lifetime Achievement Award for a variety of reasons, says curator Roger Launius: “His many accomplishments as a naval officer and astronaut have made a lasting impact on the aerospace program. He accumulated more than 7,000 flight hours, including 4,500 in jet aircraft and 715 hours in space. A pioneer in the American space program, Captain Lovell participated in four historic NASA missions. It’s a pretty illustrious career. And he’s a remarkable spokesperson for air and space activities.”