It All Started with Sputnik

An eminent space historian looks back on the first 50 years of space exploration.

With the launch of a basketball-size satellite on October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union ushered in the “Space Age” and changed the world. Sputnik 1, launched from the Soviet Union’s rocket test site near Tyuratam, Kazakhistan, was a mere 184-pound “hunk of iron almost anybody could launch,” as a U.S. Navy admiral characterized it, but it carried on its orbital trajectory a symbolism far beyond its size. It was a first step beyond this planet, and we have never known a time since when there has not been some human-made object in Earth orbit. It reversed the image of the Soviet Union as a backwater and placed the country on an international footing near to that of the United States. It also established spaceflight as evidence of progress and forward thinking among the nations of the world. Finally, it suggested to many that the destiny of humanity rested in the cosmos rather than on Earth. Belief in that destiny, for all its elusiveness, has motivated tens of thousands of people over the last 50 years to invent the machines and instruments and chart the course for planetary exploration and, perhaps, migration. (Click on the photos at left to see sample images from the Smithsonian book, After Sputnik: 50 Years of the Space Age).

In the United States the Space Age dawned with a mixture of excitement and worry. Scientists and engineers congratulated their Soviet counterparts, but political and cultural leaders called attention to the menacing significance of the achievement. After all, if this adversary could launch a satellite over our heads, it could also bring a nuclear weapon down on us. Sputnik signaled a perceived inferiority of American technological know-how, and fear prompted all manner of actions deemed necessary to “catch up” to the Soviet Union in space. The creation of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was one. Another was the National Defense Education Act of 1958, which appropriated millions for in science and mathematics education at all levels, from the elementary school to postgraduate. A generation 0f students benefited as educational programs nationwide received this infusion of new federal funding, an investment in education second only to the G.I. Bill after World War II, until the creation of the Department of Education in 1979.

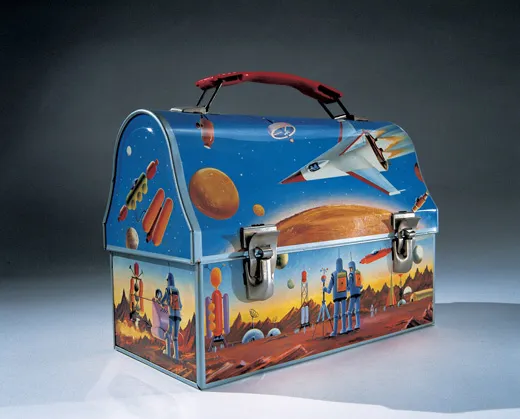

The generation of Americans who were in school during that momentous shift in priorities embraced space travel as a symbol of progress. Raised on visions of human colonies on the moon and Mars, and great starships plying galactic oceans—brought to the public by the likes of media magnate Walt Disney and German rocketeer Wernher von Braun—they saw prospects of a bright, limitless future beyond a confining, overcrowded, and resource-depleted Earth. One of the visionaries thrilled by Sputnik was 14-year-old Homer Hickam, who grew up to be a NASA engineer and author of the memoir Rocket Boys (which began as a short piece in Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine and was later adapted for the 1999 feature film October Sky). He watched “the bright little ball, moving majestically across the narrow star field between the ridgelines” of his home in Coalwood, West Virginia. It inspired him, and many like him, to devote their lives to the quest for space. Hickam recalled seeing it in the nighttime sky over his West Virginia home. “I stared at it with no less rapt attention than if it had been God Himself in a golden chariot riding overhead. It soared with what seemed to me inexorable and dangerous purpose, as if there were no power in the universe that could stop it.” Reflecting later that night on Sputnik, Homer Hickam decided that he wanted to be a part of what he considered a noble dream of space exploration.

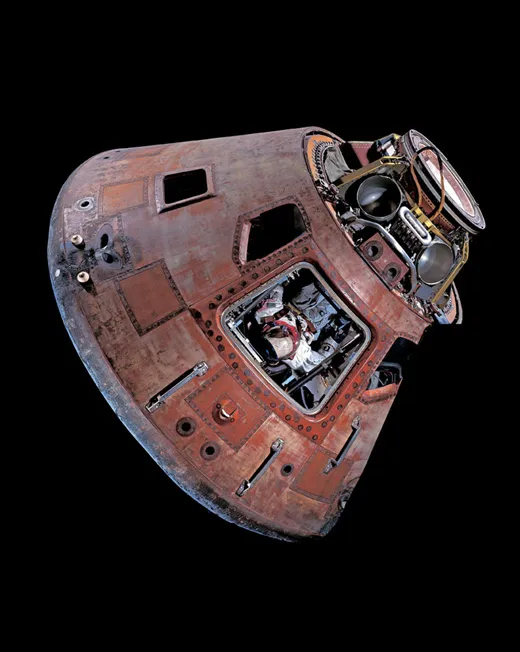

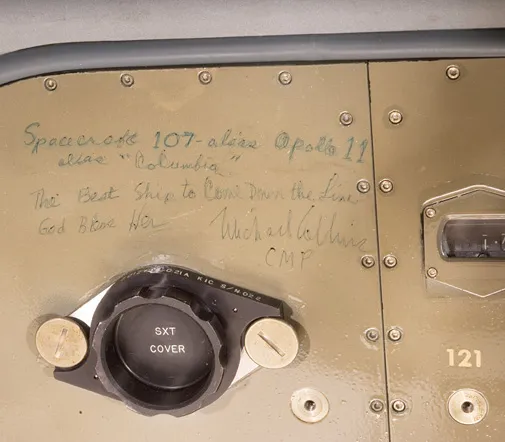

The first 15 years of the Space Age proved to be some of the most exciting of my lifetime—though I was probably four or five years old before I realized that rockets were not supposed to explode during launch. From the repeated failures of those early launch vehicles, we learned that spaceflight was not going to be easy; perhaps that is why the term “rocket science” entered our lexicon as a measure of difficulty. But the pace of discovery in the early years was also dizzying. On January 31, 1958, just four months after Sputnik 1 caused a sensation, the United States launched its first Earth satellite—Explorer—which documented the existence of what became known as the Van Allen Belts, rings of charged particles encircling Earth. The following year, Pioneer 4 sailed past the moon (after four of the aforementioned launch failures) and a Russian Luna probe crashed into it (on purpose). From the tentative first steps into space with satellites and suborbital astronaut flights through the breathtaking orbital missions of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo, the 1960s offered a vicarious thrill ride igniting the imagination of millions. As a 15-year-old, I sat with friends on the hood of a car on the night of July 20, 1969, looking at the moon and listening to the Apollo 11 astronauts on it. I understood the feeling expressed by novelist Ray Bradbury, who captured the emotion of that early heroic era of spaceflight when he commented: “Too many of us have lost the passion and emotion of remarkable things… Let us not tear up the future, but rather again heed the creative metaphors that render space travel a religious experience. When the blast of a rocket launch slams you against the wall and all the rust is shaken off your body, you will hear the great shout of the universe and the joyful crying of people who have been changed by what they’ve seen.”

The moon landings changed us. Certainly the Apollo program was one side of a political contest, a surrogate for war. But it also stretched our imaginations and made us believe that anything we set our minds to we could accomplish. “Yes, indeed, we are the lucky generation,” commented CBS television news anchor Walter Cronkite, for we “first broke our earthly bonds and ventured into space. From our descendants’ perches on other planets or distant space cities, they will look back at our achievement with wonder at our courage and audacity and with appreciation at our accomplishments, which assured the future in which they live.”

Opportunities in space appeared boundless. We expected to see made real the vision of spaceflight depicted in the classic 1968 science fiction movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey, wherein Stanley Kubrick depicted a human race moving outward into the solar system. A great space station orbited Earth, serviced by a reusable, winged spacecraft traveling from the globe’s surface. In this film, activities in low Earth orbit have become routine; in the first segments, many of the functions are carried out by commercial enterprises. The shuttle to the space station is flown by Pan American, the station has a Hilton hotel, and communications are supplied by AT&T.

Instead we got the space shuttle. For the last two decades of the 20th century, it confined us to lowEarth orbit. I found myself agreeing with the character of Leo McGarry, the White House chief of staff in the television drama “West Wing,” when asked about NASA’s activities: “Where’s my jet pack, my colonies on the moon? Just a waste.” The Apollo generation felt betrayed by the space shuttle, which was invented not for the exploration we thought Apollo had promised, but for reliable and inexpensive access to space. Even that purpose, as the early rocket failures foreshadowed, was too difficult to achieve. After two tragic accidents—Challenger during launch on January 28, 1986, and Columbia during reentry on February 1, 2003—many agreed when NASA administrator Mike Griffin branded the program a “mistake” in autumn 2005. No wonder a consensus emerged after the second accident that by 2010 the vehicle should be retired. Had an International Space Station not been half-completed, and had the shuttle not been necessary to finish the work, it probably would not have returned to flight at all.

If the human spaceflight effort seemed moribund at the end of the twentieth century after the ambitious effort to reach the Moon, a robust robotic science program provided continual excitement. Since the dawn of the Space Age flights to every planet of the solar system have expanded them from points of light in the nighttime sky to unique worlds of remarkable variety and complexity. The stunning missions to explore the outer solar system—Pioneers 10 and 11, Voyagers 1 and 2, Galileo, and Cassini—have yielded a treasure of knowledge about our universe, how it originated, and how it works. Exploration of Mars has shown powerfully the prospect of past life on the red planet. Missions to Venus and Mercury have harvested knowledge about the origins and evolution of the inner solar system. The stunningly successful Hubble Space Telescope has transformed our understanding of the cosmos. Most important, we have learned that so far as we know Earth is the only place where everything necessary to sustain our life is, as Goldilocks found in the fairy tale, “just right.”

For all their accomplishments these robots have not replaced the dream of human movement beyond Earth that astronauts flying to the Moon engendered. Many of us still believe that humanity has only a finite period of time to colonize other worlds before resources on Earth are unable to sustain human migration. Resource depletion—and perhaps environmental degradation, climate change, or nuclear war—could soon close off this opportunity. Carpe diem! Many of the Apollo generation believe that if we do not seize this opportunity while circumstances on Earth permit, interplanetary travel will eventually become impossible.

Whether or not it proves attainable in the future, President George W. Bush’s call on January 14, 2004, to reach the moon and Mars during the next thirty years makes clear that a belief in a limitless frontier in space still motivates us. Thousands may yet heed the siren call of space and walk in the footsteps of “Everyman,” described in a poem by Mary Jean Holmes as the figure who enabled the astronauts to explore the moon. Holmes writes:

For I’m the man who took up tools and laid out the designs.

Of starships, I’m the one who built their sleek and burnished lines.

I’m everyman who ever fashioned cold refined steel

Into the dreams of spaceflight, I’m the one who made them real.

The first fifty years of space exploration were marked by fantastic dreams and a compelling sense of destiny in space, and the thrill of exploration continues into the next half-century. During the second fifty years of the Space Age, who knows what discoveries will alter the course of the future? A limitless future for humanity in space remains the critical but elusive goal of the Space Age. Russian spaceflight pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky said it best, “The Earth is the cradle of the mind, but we cannot remain forever in the cradle.” What Sputnik taught us is that this cradle is not a cage and that we can leave it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/launius-main.jpg)