America by Air: Jack Northrop’s ‘Beautiful Ship’

In 1931, a six-passenger airplane hinted at the many aeronautical wonders to come.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/b5/32b5c420-1819-41bf-afcc-2e66f5e1ccb2/13m_dj2021_northrop4aalphahopebettertk_a19761144000cp05_live.jpg)

The Northrop Alpha was introduced in 1931 to a “chastened and deflated” aircraft industry battered by the Great Depression. But the Scientific American reporter assigned to cover the National Aircraft Show in Detroit in July that year couldn’t help noting that the aircraft was “a beautiful ship, streamlined to the last degree,” and that it introduced remarkable advances to insulate passengers from noise, heat, and cold.

“The Northrop Alpha is a very modern airplane for its time,” says National Air and Space Museum curator F. Robert van der Linden. “It’s one of the first all-metal, semi-monocoque aircraft in service in the United States. That’s why it’s in the collection, and why it’s highlighted in the America by Air gallery.” In semi-monocoque construction, the aircraft skin is tightly stressed and absorbs some of the twisting and bending forces an airplane experiences in flight. The addition of stringers reinforces the structure, allowing the sheet-metal skin to carry most, but not all, of the weight. “The semi-monocoque structure is a crucial design element that reduces weight, thereby increasing payload,” says van der Linden.

The Alpha was designed to carry mail, but could carry six passengers if needed. Though the passengers were in a closed cabin, the pilot sat out in the open. “The pilots preferred it,” says van der Linden. “The early 1930s were a transition period, and the transition wasn’t in technology; it was in the mindset of the pilots. They didn’t trust instruments, and thought they couldn’t fly as well unless they were out in the environment. It was difficult to get them ‘inside,’ so to speak. There was a lot of resistance. This was one of several ‘compromise’ airplanes, which featured an open cockpit and an enclosed cabin.”

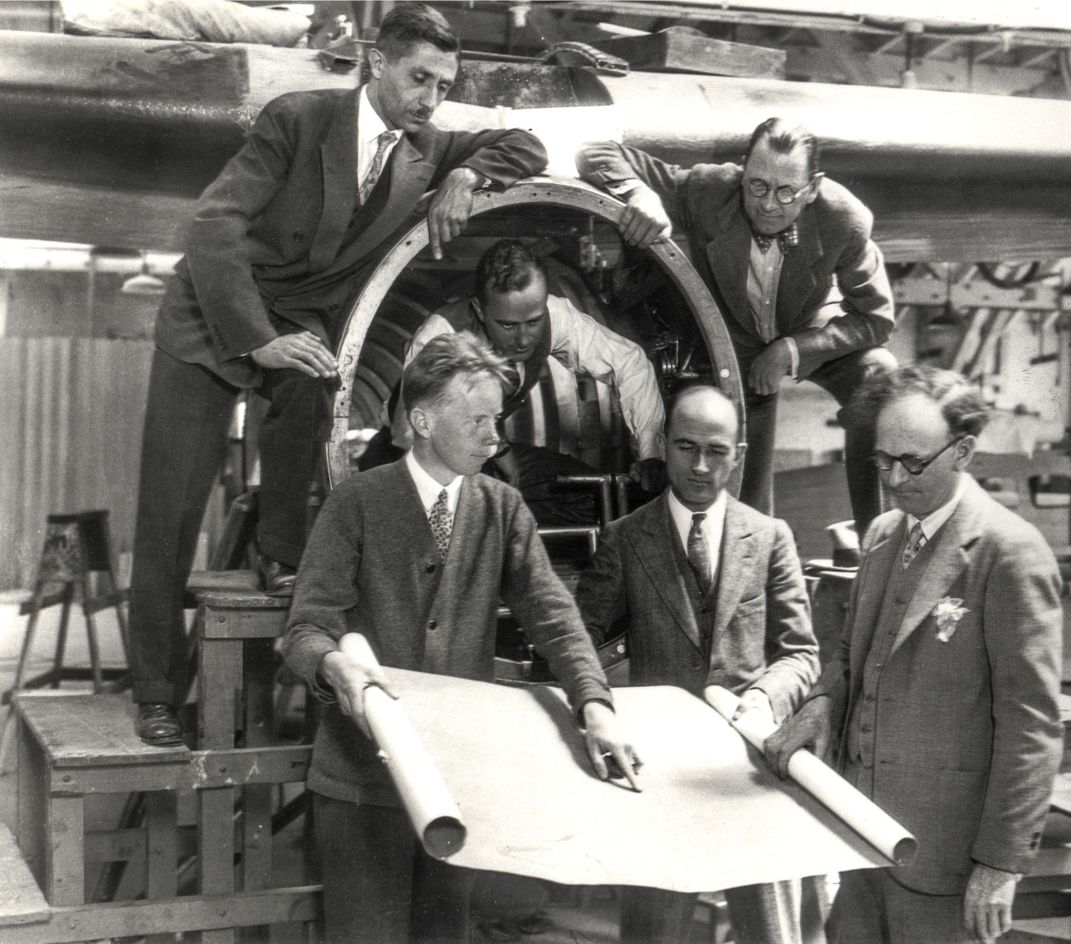

The aircraft was the brainchild of Jack Northrop, a self-taught engineer who had worked with the Loughead brothers in Santa Barbara, and with Douglas Aircraft in Santa Monica, before joining Allan Loughead at the newly formed Lockheed Aircraft Company in 1927. There Northrop would design the innovative Vega, used by Wiley Post in his 1931 record-setting around-the-world flight, and by Amelia Earhart in 1932 when she became the first woman to make a nonstop, solo transatlantic flight.

The Alpha wasn’t just a thing of beauty. Besides its stressed-skin construction, its cantilever wing featured an internal frame made of aluminum sheets, formed into channels and riveted to one another as well as to the wing skin. The result was a lighter, inexpensive, rugged wing that would be later adapted to the Douglas DC-3.

The Alpha influenced aeronautical design in another way: The initial version had the unstreamlined tripod landing gear found on other aircraft of the time. But by 1930, Northrop was studying both retractable landing gear as well as “wheel-pants,” covers that would smooth the airflow around extended gear. In a 1994 article in Technology and Culture, historian Walter Vincenti tells the story of the wind-tunnel tests Northrop conducted on a model of the Alpha at the California Institute of Technology. Engineers were surprised to discover that the reduction in drag was nearly the same for both retracted and “pants-type” landing gear. Wheel-pants would appear first on the Northrop Beta; eventually, all of TWA’s Alphas had their original tripod landing gears replaced.

After larger twin-engine transports took over passenger flights in commercial aviation, the Northrop Alphas turned to carrying freight, including, says van der Linden, freshly cut gardenias, silk worms, medical serums, and auto parts.

The Museum’s Alpha was the third built, and had multiple owners. In 1930, Colonel C.M. Young, the Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics, flew it to inspect airports and runways. It would later be sold to Transcontinental & Western Air, Inc.; in 1933, in his role as technical advisor to TWA, Charles Lindbergh flew the aircraft at least once. The Alpha went through several more owners before arriving at the National Air and Space Museum in 1976, just in time for its grand opening on the National Mall.

Northrop’s genius put him squarely in the middle of the early U.S. aviation industry—not only did he work with the Lockheeds and for Douglas—but he also designed the wing of the Ryan M-2, which was used on the Spirit of St. Louis. “He got around,” says van der Linden. “Everybody thinks about his amazing flying wing. But everything he did before and after the flying wing was equally impressive.” The world got its first true look at Jack Northrop’s genius with the Northrop Alpha, which matured into the Gamma, one of history’s most capable airplanes of exploration.

America by Air is made possible by the support of these founding donors: American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, United Airlines, Alaska Airlines, JetBlue, Frontier Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines, Spirit Airlines