In 1956, the Soviets held first place — briefly.

Jet Race

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jet-Race-631.jpg)

Anatoly Gorbachev remembers that he was supposed to be flying from Peking back to Moscow that moonless night in October 1958. But his friend Garold Kuznetsov asked if he could take his turn in the pilots’ rotation. Kuznetsov was trying to prove himself as a captain of the Tupolev Tu-104A, the Soviet Union’s leap into jet-powered civil aviation, and needed to log flight time. Gorbachev said okay.

Both men knew what the Soviet public at large did not. Two months earlier, another Tu-104, flying across eastern Siberia, had encountered a powerful updraft and been pitched 4,000 feet above its cruising altitude. It then lost power and plunged 40,000 feet straight down. The bodies of the crew and passengers were strewn across more than a mile of forest-covered mountain terrain. Tupolev’s breakthrough airliner had experienced two other mid-flight engine failures in the first half of 1958, both of which had ended in miraculous recoveries.

Kuznetsov’s outbound flight to China passed without incident. But crossing the Urals on the return leg, his airplane hit turbulence and fell prey to the phenomenon ground crews already had a name for: podkhvat, or “the grab.” His -104 sailed helplessly upward, flipped over, and began diving, his descent looking like a gigantic corkscrew. Cockpit instruments failed, leaving Kuznetsov disoriented in the darkness.

Kuznetsov’s radio still worked, however, and for the last two minutes of his life he talked traffic controllers through whatever details he could gather of the aircraft’s performance—a human black box offering data for the great designer Andrei Tupolev and his workshop to study later.

At first, the imperious Tupolev refused to acknowledge any fault in his masterwork. “There is nothing wrong with the plane,” he is reported to have fumed after the 1958 string of accidents. “It is you who do not know how to fly it.” But prodded by the Soviet Council of Ministers, he eventually made changes that allowed the -104 to stay in use for two decades, ferrying 100 million passengers on visits to distant relatives or errands for the Soviet state.

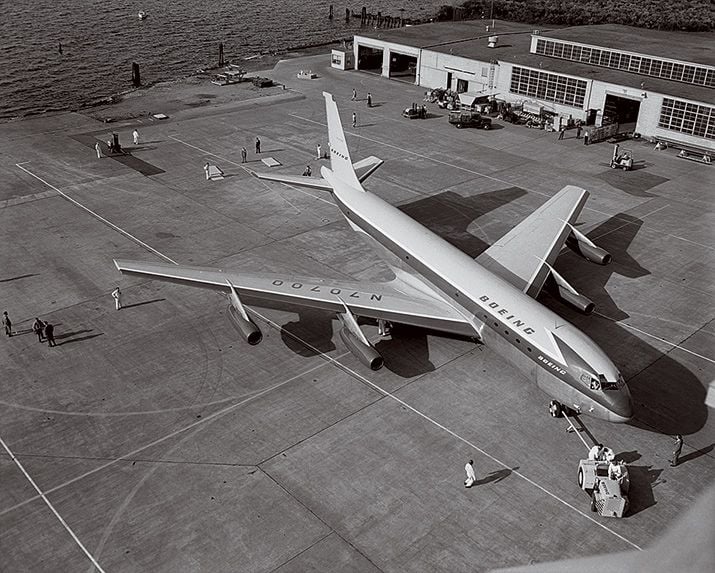

Before the Space Race, before the fatal fire on Apollo 1 or the deaths of three cosmonauts returning to Earth aboard Soyuz 11, there was a Jet Race, whose tragedies and triumphs are now mostly forgotten. Begun in the last years of World War II, when the combatants struggled to get military jets into the skies, the competition continued into the 1950s, when the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union were scrambling to field the first passenger jets.

The British were the first to build a passenger jetliner, the de Havilland D.H.106 Comet, which was tested in 1949 and started flying scheduled routes in 1952. But two years later, when two of the airliners broke up in mid-air within four months of each other, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the fleet grounded. The Soviets can claim the first continuous commercial jet service, which they began with the -104 in 1956, two years ahead of the debut of the iconic Boeing 707 and the resumption of flights by the Comet. The -104 also had its share of disasters, but Tupolev and the Soviets managed to learn from them and keep flying.

Almost half a century after the accident that killed his friend, Gorbachev is sharing tea and cookies with two other fliers from the original group of -104 pilots and reminiscing about those pioneering days. In 1958, Gorbachev was, at age 26, the youngest captain in the Soviet Union. Now 80, he is still the junior member of his peer group. His companions, Nikolai Grokhovsky and Vladimir Ushof, are octogenarians, stalwart and still more than a bit stentorian. The setting is a soggy winter afternoon at the Aeroflot Museum, a scarcely visited three-room affair hidden in a faceless office complex across the road from the domestic terminal at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport. Sitting at a foldout table amid a jumble of skyward-pointing model airplanes and jaunty stewardess uniforms from the 1960s, the three veterans talk about the old days until well after dark.

None of the pilots ever met the mighty Tupolev. But they remember him with respect despite his hot-blooded insult to their comrades who died flying his machine. “Tupolev did everything he could as a designer to ensure safety,” Ushof booms. “You have to remember that the Tu-104 flew at a completely new altitude, where meteorologists had no experience of the winds and currents.”

Considering the breakneck pace of the -104’s development, it seems a wonder that it flew at all. These days, when a new aircraft can spend a decade or more in design and testing, it is hard to imagine the pace of the early cold war, when aerospace manufacturers cranked out rapidly evolving generations of military aircraft and the technology spilled over somewhat haphazardly into civil aviation. The -104 was created in 14 months in 1954-55 on the platform of the Tu-16 long-range bomber, known in the West as the Badger, which was itself virgin technology.

During this hectic period, Andrei Nikolaevich Tupolev was at the height of his long, eventful career. Born in 1888 near the central Russian city of Tver, Tupolev went to college at the Moscow Imperial Technical School. One of his professors was Nikolai Zhukovski, the revered father of Russian aviation, who in 1909 taught the country’s first university course in aerodynamics.

Zhukovski and Tupolev stuck together after the Bolshevik revolution, creating the Central Aero/Hydrodynamics Institute, or TsAGI, in 1918, the cerebrum for a vast industry to come. The first aircraft with Tupolev’s name on it, a half-wooden monoplane designated ANT-1, flew in 1923. Two years later, Tupolev launched his first military craft, a reconnaissance sesquiplane called ANT-3.

In 1937, Tupolev’s ANT-25 carried Valery Chkalov over the North Pole to America’s Washington state, a feat generations of Soviet propagandists tirelessly glorified. “Andrei Nikolaevich’s real genius was as an organizer,” says Vladimir Rigmant, house historian and curator of the one-room Tupolev Museum, located at the Moscow headquarters of what is today called Public Stock Company Tupolev. “He could see a practical means for realizing complex ideas.”

Getting to see Rigmant, who has been employed at the Tupolev Works since the 1970s, is not easy. Like much of Russian industry, the company still acts like it has important secrets to protect. My persistence is rewarded with a trip into Moscow’s industrialized eastern quadrant to a squat 1960s office building that only a central planner could love.

Carefully unlocking an unmarked door off to one side of the large, bare lobby, Rigmant ushers me into his cabinet of treasures. He whips out a pointer to review a half-century’s worth of aircraft models jammed tail to nose in the constrained space, rushing through a litany of years and model numbers: Tu-2,Tu-70, Tu-205, Tu-154. On the wall is a family photo of the designer with his wife Julia, who worked closely with him.

Yet scarcely four months after Chkalov’s flight, Tupolev was caught in the madness of Joseph Stalin’s party purges. He was arrested as a saboteur in October 1937, and under torture confessed to a wide range of “crimes” against the Soviet people.

Stalin and his secret police chief, Lavrenti Beria, soon realized they had made a mistake, however. War was threatening Europe, and without its guiding spirit, Soviet aviation was in chaos. Tupolev was rescued from Moscow’s Butyrskaya prison in late 1938, and transferred to Bolshevo prison to head a new design bureau controlled by Beria’s secret police, the NKVD. There he created a Stalinist version of Schindler’s list, handing his captors the names of some 150 imprisoned engineers and scientists whom he declared essential to his patriotic work. Beria dutifully retrieved this elite cadre from throughout the Gulag archipelago, undoubtedly saving the lives of most of them.

While still prisoners, Tupolev and his fellow designers created the Tu-2 bomber. The Soviet supreme court granted Tupolev clemency as the Nazis overran western Russia in July 1941, just in time for him to evacuate his workshop to Omsk, in Siberia.

After the war, Soviet aviation was enriched by technology shared willingly or otherwise by the country’s Western allies. In 1944, four American Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers were forced to make emergency landings at Vladivostok after a raid on Japan. Stalin had them flown to Moscow and set Tupolev to work reverse-engineering them to create a Soviet version. The result was the Tu-4, which first flew in May 1947.

Simultaneously the master designer developed the Soviet Union’s first jet-powered bomber, using Rolls-Royce Nene and Derwent engines, which Britain briefly made available under license. This aircraft was the Tu-12, which flew in December 1947. In the early 1950s, Tupolev returned to turboprop technology for the Tu-95 strategic bomber—the Bear—which was still flying when the Soviet Union crumbled in 1991.

Even in this frenzy of military invention, Tupolev did not forget airliners. He scavenged parts of his precious Superfortresses to make a trial civilian version of the Tu-4. And as soon as the Tu-16 was aloft in 1952, he began lobbying the Communist hierarchy for a passenger variant. Tupolev’s conversion plans made little progress while Stalin was alive. The dictator traveled, with rare exceptions, by train, and thought ordinary citizens should do the same. In Stalin’s mind, airplanes and the limited resources available to build them were for war.

On the other hand, Nikita Khrushchev, the premier who took power after Stalin died in 1953, loved flying. He saw civil aviation as a pillar in his grand strategy to “catch and overtake” the West. Tupolev was invited back in late 1953 to pitch the civilian Tu-16 idea to the Communist Party Central Committee, and by June 1954 had an order to get cracking. The Tu-104 was on its way.

Converting a spanking new jet bomber to civilian use turned out to be not so simple. The bomb bay, for example, had to be transformed into a baggage compartment. But the core problem was that a passenger liner needed a pressurized cabin, and numerous extra holes cut into the fuselage for windows and doors.

The British investigation into the Comet failures was delayed because both crashes had taken place at sea, making wreckage recovery difficult. Tupolev from the first rightly suspected the airplane’s body had suffered metal fatigue. One of his adjustments was simply to add heft to the -104, thickening the fuselage skin to 1.5 mm, compared to the Comet’s 0.9 mm. The extra weight halved the -104’s range to 1,900 miles and considerably increased fuel costs, but the apparatchiks approved of Tupolev’s caution.

Tupolev also opted for round windows instead of the Comet’s square ones, eliminating the corners as pressure points. He built an enormous testing pool at TsAGI’s headquarters, outside Moscow, where jet mockups could be submerged to simulate atmospheric pressures. And he outfitted the -104 with avionics that Soviet aircraft hadn’t used before, such as radar.

By the late 1950s, Tupolev’s shop had burgeoned to about 10,000 employees and occupied a sprawling complex in the industrialized eastern part of Moscow; across the street from the design center was a factory for prototypes. This mass of humanity was efficient enough that the -104’s first test flight took place two months ahead of schedule, in June 1955.

By March 1956, Khrushchev was ready to use Tupolev’s creation to score an international PR victory. He ordered the -104 to fly to London carrying officials who were laying the groundwork for an East-West summit there. According to a Russian TV documentary, Khrushchev himself wanted to ride the little-tested jetliner into Heathrow, and Tupolev had to race to the impetuous leader’s dacha to talk him out of it.

For British aviation professionals still mourning the loss of the Comets, the -104’s arrival was a mini-Sputnik moment: an unsuspected Soviet technological advance falling from the sky, causing both admiration and anxiety. “The Russians are far ahead of us in the development of such aircraft and jet engines,” retired RAF Air Chief Marshal Philip Joubert de la Ferté told the BBC at the time. “Many in the West will have to change their views on the progress made by Soviet aircraft technology.”

Julia Tupolev’s interior for the -104 was a sensation in itself. Confounding stereotypes of Bolshevik austerity, it offered lavish comfort in the air. “The cabin fittings seemed to be from the 1930s Orient Express school of luxury,” with porcelain toilets and heavy curtains, a former ground staffer at Gatwick recalled decades later in an online enthusiasts’ forum. Pilot Vladimir Ushof remembers that the cabin was “in the style of Catherine the Great.” Within a year or two, economy conquered Mrs. Tupolev’s aesthetics, and the -104 was reconfigured with standard row seating for 70 passengers rather than the original 50.

The aircraft’s triumphant reception could not mask trouble under the hood. Tupolev had not managed or bothered to control the fiery exhaust the hastily converted bomber emitted at takeoff. “Sheets of flame from the aircraft’s ‘wet start’ [starting a turbine engine with fuel already pooled in it] would cause a spectacular exodus of ground staff,” a former Gatwick employee recollected.

Back home in Russia, first-generation -104 pilots were doing their best to iron out other serious wrinkles before the airplane took on innocent members of the general public. For one thing, runways both inside and out of the Soviet Union were too short for the new jet, which took off at 186 mph, compared with an average of 124 mph for piston-engine aircraft. According to the -104’s specs, safe takeoff and landing required a 1.5-mile runway. When the airplane started flying, only one Soviet civilian airport, at Omsk in central Siberia, met the requirement. The tarmac at France’s Le Bourget, where the -104 was naturally sent to show off at the biannual Paris airshow, was 1.4 miles long. Amsterdam, an early commercial destination, offered just 1.1 miles.

Landing was further complicated by the -104’s absence of a reverse gear. If a pilot felt the brake was insufficient to halt the barreling 67-plus-ton craft, he could deploy two parachutes from the tail. This strategy held its own risks, though. “If you had a crosswind, the plane could start spinning like a weather vane,” Gorbachev recalls, adding an understatement: “This created certain complications.”

Nevertheless, the Tu-104 entered regular passenger service in September 1956 and served Aeroflot faithfully for more than 20 years. About 200 were built. They enabled those Soviets privileged enough to be cleared for foreign travel to fly nonstop around Europe, and ordinary citizens to more conveniently reach remote domestic destinations like Irkutsk, near Lake Baikal.

To prove the first journey to London was not a fluke, Khrushchev sent the Bolshoi Ballet back on a -104 later in 1956. At one point, Aeroflot landed three -104s at Heathrow simultaneously, to disprove a British press report that only one prototype was operational.

When the -104 did run into trouble, it was not from the takeoffs and landings that harrowed the pilots, nor from the fuselage, which Tupolev’s measures indeed rendered sturdier than the de Havilland Comet’s. Rather, the aircraft could not always remain stable in the wicked currents it encountered at its little-explored cruising altitude.

After four incidents of “the grab” in 1958, an inquiry was launched. With no public outcry to fear, the Kremlin kept the -104 flying, though reducing its maximum altitude to 10,000 meters (32,841 feet), and gave Tupolev a month to come up with remedies. Soviet engineers identified the basic flaw in the aircraft’s angle of attack in flight, and changes were made in the wing design and flight controls, which resolved many, but not all, of the problems.

In the early 1960s, Ushof joined a -104 squadron devoted to ferrying government grandees, and flew Khrushchev’s successors, Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin, on state business at home and abroad. (Khrushchev himself stuck mostly with a personal pilot named Nikolai Tsybin, who, the -104 flyers remember with some lingering superiority, never got the hang of handling jets.) But Soviet civil aviation’s moment of glory on the world stage was brief. In 1958 the Boeing 707 began offering passenger service with a range of 6,250 miles, more than triple the -104’s, and the Soviet Union never really caught up.

Transport bureaucrats wasted valuable years debating whether jet travel was suitable for civilians after all—today, the pilots guess that the doubts were partly spurred by the -104’s serial accidents. Tupolev’s own next effort, the Tu-114, was a conversion of the Tu-95 transcontinental bomber. The most prolifically produced Soviet airliner of the 1960s was another turboprop, the Ilyushin Works’ Il-18.

It wasn’t until 1972 that Tupolev returned with the first jet he designed from scratch as a passenger carrier, the Tu-154. Within the Communist sphere of influence, it was a hit. More than 1,000 Tu-154s were manufactured, and some 200 are still flying.

Aeroflot retired the Tu-104 in 1979. The military kept a few around for staff transportation until 1981, when a -104 crashed on takeoff from Pushkin, near Leningrad, killing 52, including most of the top commanders of the Soviet navy’s Pacific fleet. Investigations determined that the airplane was overloaded, but the catastrophe stirred the ghost of Garold Kuznetsov, and the rest of the fleet was mothballed.

In the post-Soviet period, Russian civilian aircraft makers have performed dismally. Aeroflot, which is still in service as Russia’s international flag carrier, and the new privatized airlines that have taken over most domestic routes have all moved to retool with Boeings and Airbuses, despite steep import tariffs. Russian-made MiG and Sukhoi warplanes continue to sell around the world, but the only recent Tupolev sale on the civilian side was to Syria, whose national airline agreed in 2011 to buy three Tu-204s for a reported $108 million. Given subsequent events in Syria, even that deal looks questionable.

The Kremlin focused its civil aviation efforts over the past decade on developing the so-called Sukhoi Superjet, a 75- to 90-seat single-aisle craft designed to compete with Embraer and Bombardier in the global short-haul market. So far, the Brazilians and Canadians have little to fear.

While the Superjet made what was supposed to be its maiden flight in 2008, just a dozen or so are actually in service today, mostly with Aeroflot. The only international customer to date is Armenia’s national airline, Armavia.\A contract with Indonesia’s Kartika Airlines was set back—along with the Superjet’s prospects in general—when a demonstration flight in May 2012 crashed into a mountain in West Java, killing all 45 people on board. Even the patriotic ex-Tu-104 pilots can muster little enthusiasm for the unlucky short hauler. “They can build it, but who will buy it?” quips Anatoly Gorbachev as he waits for a crowded bus that will creep through the evening rush-hour traffic from Sheremetyevo into Moscow.

Back in town, the great Tupolev Works on the Yauza River is physically as well as economically diminished. The design center soldiers on in the same unprepossessing building as Vladimir Rigmant’s museum. But the factory has been torn down and in its place stand gleaming new condos sporting the name “Tupolev Plaza.” Yet the humble rooms, for decades, spawned technology that matched the world’s best and sometimes claimed the title.

Craig Mellow is a freelance journalist in Staten Island, New York.