John Young, True Believer

The longest-serving astronaut was also among the most visionary.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/64/3a64ecbc-037d-4f51-9825-685eb7fe735e/young_gt_3.jpg)

Even if he hadn’t made two trips to the moon and walked on its surface, John Young, who died last Friday at the age of 87, would still be a space legend. No astronaut has ever done, and probably never will do again, anything quite as steel-nerved as when Young—at the unheard-of age of 50—and co-pilot Bob Crippen rode the untried space shuttle into orbit on its maiden flight on April 12, 1981. Back on Earth two days later, Young spoke like the True Believer he always was: “We’re really not too far, the human race isn’t, from going to the stars.”

But the longest serving astronaut, who made six trips into space during his four decades at NASA, was never starry-eyed. As much as anyone who ever climbed on top of a rocket, Young was unblinkingly mindful of the risks of flying in space. Crippen recalled the time he and Young went to the Thiokol factory in Utah to witness the testing of a shuttle Solid Rocket Booster. After the thunderous test-firing was over, a Thiokol exec turned to Young and said, “Well, John, how’d you like to ride one of those?” Replied Young, “I’d much rather ride two of ‘em.” In other words, if only one of the shuttle’s twin SRBs ignited at liftoff, it would be a very bad day.

Young’s deadpan one-liners and country-boy drawl masked the keen intelligence of a talented engineering pilot (read this profile from the September 2005 issue of Air & Space). Houston space center director Robert Gilruth once told an associate, “John Young is the best engineer I’ve got.” As chief of the astronaut corps, a post he held from 1974 to 1986, Young often brought his sharp-eyed scrutiny to bear on the safety of his people. In the months before the shuttle Challenger exploded during launch in January 1986, Young was clearly worried that in the push to make spaceflight routine, NASA was getting too close to the edge. “We’re going to kill somebody,” he would say to a room full of astronauts at their Monday-morning pilot meetings. After the accident, his memos alerting managers to potential disasters became public knowledge, and some speculated they contributed to his being “kicked upstairs” into a management position, ending his spaceflight career.

Even then, Young was a tireless crusader for space exploration. He firmly believed humans must become a multi-planet species if they are to survive, and would often cite a list of extinction-level threats, from asteroid impacts to super-volcanoes. I can remember how frustrated he was, during the mid-1990s, that a quarter-century after the last Apollo landing, NASA still had no firm prospects for going back to the moon.

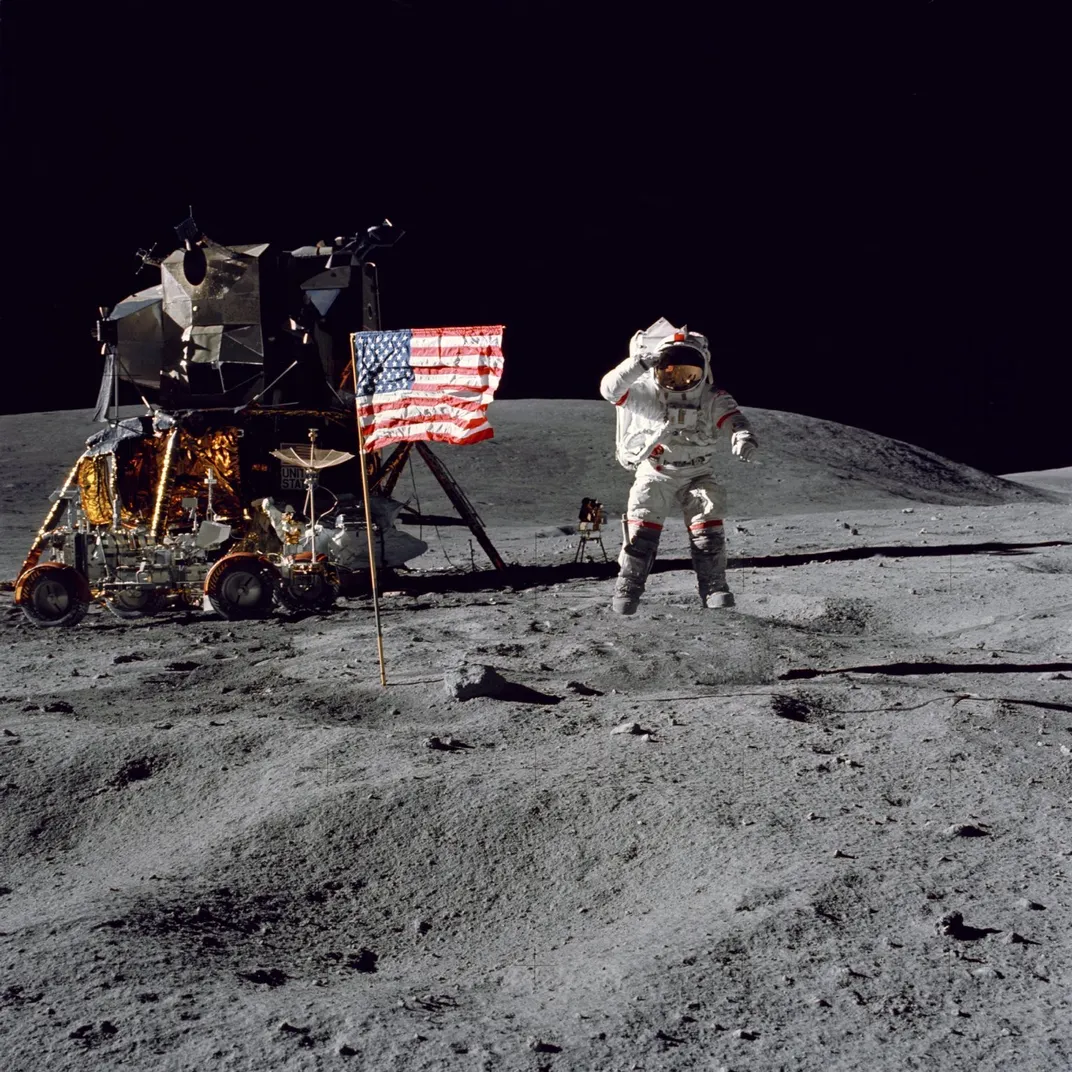

Young never lost his interest in the world he had explored in 1972, as commander of the Apollo 16 lunar landing. He would often show up at the annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston, and was always anxious to hear about new discoveries. When others claimed the moon was a far less exciting destination for NASA than Mars, Young was quick to disagree. “It’s anything but boring,” he told me in 1989. “We don't even begin to understand it.” Young’s footprints are still there, for anyone who wants to take on the formidable task of trying to fill them.