Just Doing Their Job

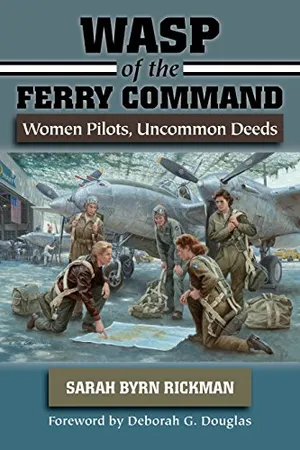

WASP of the Ferry Command.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/dc/c0dc95a3-4aee-49c8-a042-4a9d5df9fc08/wasp_congressional_gold_medal.jpg)

During World War II, thousands of male pilots were stationed overseas, so the job of ferrying new aircraft from manufacturing plants to U.S. military bases sometimes fell to women. Beginning in 1942, female civilian pilots, flying for the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP), completed more than half of these domestic ferry flights. Drawing from letters, diaries, and oral histories, Sarah Byrn Rickman recounts the personal stories of many of the pilots in her latest book, WASP of the Ferry Command. Rickman spoke with senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in August.

Why did you decide to write this book?

If the WASP program is, as some say, the best-kept secret of World War II, then the story of the WASP of the Ferry Command is buried deep in the locked vault of time. I wanted to bring that story to light. In early 1940s America, many women did not drive, and even if they did, they wouldn’t have considered driving across the state line, much less across country—alone. But these women pilots mastered cross-country traveling at the controls of the fastest aircraft we possessed at the time.

Are there any inaccuracies or myths about the WASP that continue to be reported?

Yes. There’s a myth that the WASP ferried aircraft overseas. Fact: They did not. General William H. Tunner assigned his two top women pilots, Nancy Love and her second-in-command, Betty Gillies, to ferry one B-17 in a group of 200 B-17s bound for Prestwick, Scotland, in September 1943. When General “Hap” Arnold got wind of it, he ordered the flight stopped. Two male pilots were dispatched to Goose Bay, Labrador—where the B-17 and its crew were weathered in—with orders that the women return to base and the male pilots take the flight the rest of the way to Scotland. Arnold did not want women flying into a battle zone, and promptly issued a memo to that effect. After that, no other overseas flights for women were scheduled.

During your research on the WASP, were you ever surprised by anything?

I’ve been studying the WASP for 25 years now. I’ve personally interviewed approximately 45 of the women as well as a handful of their relatives. I’ve found no mold, other than love of flight. Many never flew again after the war, but that had more to do with economics, opportunity, marital status (which in most cases came soon after the war) and motherhood. Several went back to flying later in life. Some never left it. A few hung on for awhile after the war ferrying surplus aircraft, but the thrill, the excitement, the big, fast Army planes, were a thing of the past and most quit in disgust or sheer disillusionment. I think, for most, flying became an exciting, heady opportunity and moment in time, and the coming of such a moment—like World War II—is very, very rare. The real surprise, for me, is the number that applied—more than 25,000 women. But only 1,830 were accepted, and 1,102 went on to serve.

What is the legacy of the WASP?

They are called heroines. But these young women rarely were called upon to do heroic things. They studied, worked hard, learned; they went to school, hit the books, and they flew. Heroines? No. Real women doing a demanding job that required skill and dedication? Yes. And they got pretty good at it. They are women worth emulating, not putting up on a pedestal. Thank them for their service—they gave a chunk of their youth in the process.

How are their contributions viewed today?

Many view their contributions through rose-colored glasses, and I think that does the WASP a disservice. Their contributions were real and needed at the time. They are old women now, with old women’s ailments, losses, memories of the good and bad, but when the talk turns to flying, their eyes light up, smiles break across their faces, and they begin to tell you about one of their flights 70 years ago. Every one of them will still jump at the offer of a flight, even if she has to be lifted and folded into the airplane she used to get into by jumping up on the wing and throwing her leg over the side of the cockpit. She’ll take that ride—be it a Stearman or a P-51 rigged with a backseat. And if the pilot-in-command gives her stick time, it all comes back.