Just One Word: Plastics

The world’s first all-composite airplane may fly again.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Just_One_Way_11-01-11_2_FLASH.jpg)

Decades before you could buy a mass-produced composite aircraft, Leo Windecker booked a Cessna 172 demo ride. After a hammering from turbulence in the south Texas sky, Windecker examined the airplane’s all-aluminum construction. “He was horrified by how flimsy it was,” recalls his son Ted, an aerospace engineer in Austin.

The eclectic dentist/inventor, who died last year, had experimented with glass-fiber-reinforced materials and contemplated molding recreational vehicles. Now he thought, Why not a plastic airplane?

“In our garage in Sugar Land,” Ted says, “Dad shaped a block of styrofoam like a Piper Comanche wing and coated it with a sealer, fiberglass cloth, and polyester resin.” Some of his patients, scientists at nearby Dow Chemical Company, provided advice and higher-tech Dow materials, and with their backing, CEO Herbert Dow, an airplane enthusiast, okayed funding for a composite airplane. “Dad never returned to dentistry,” Ted says.

Windecker envisioned a fixed-gear trainer. Herb Dow preferred a sportplane to rival the popular Beechcraft Bonanza—a fateful target market.

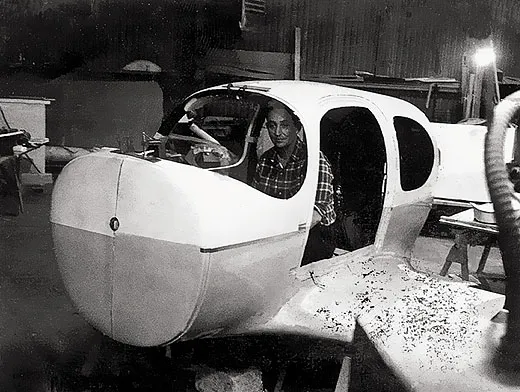

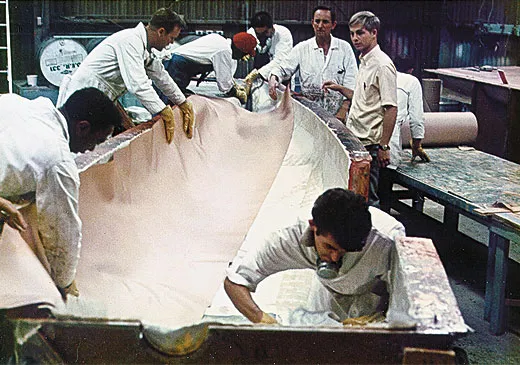

While Windecker’s sons, Ted, Bob, and Skipper, swept shop floors, organized tool bins, machined metal, and fabricated wing components, Leo and his wife, Fairfax, researched nonwoven unidirectional fiber and exotic epoxy resins. A patented composite, Fibaloy, resulted: lighter than aluminum, twice as strong. In heated vacuum molds, Fibaloy wings were baked as integral units—wiring, fuel lines, and plastic tanks enclosed—while the fuselage popped out in halves, to be glued together like model airplane pieces.

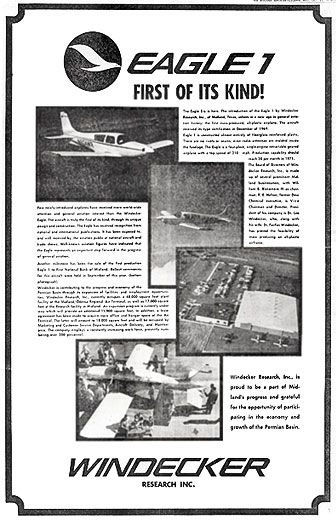

In 1967, a consortium of Midland, Texas civic boosters acquired Windecker Research. Successful real estate and oil men, most former military pilots, “they knew little about manufacturing airplanes,” Ted Windecker says. Rancher and land investor William P. Blakemore, with his huge financial clout, became majority stockholder and alpha-chairman. Ted contends Blakemore undercapitalized the project.

The first prototype incorporated fixed landing gear. But Windecker president Ken Smith mandated retractable gear, designed in-house. “In my opinion, that one decision alone killed the company,” says Dan Black, founding board member and former Air Force pilot. New engineers were recruited, mostly from Cessna. “Obviously, these people didn’t have a lot of experience designing retractable landing gears,” Ted says. Successive revamps failed structural tests and hemorrhaged money and labor, setting certification back by months. One exasperated gear component supplier finally asked, “What’s this for? A Boeing 747?”

Rivet-free and nearly seamless, the Eagle was an aerodynamic banana peel. Its fuselage displayed silhouettes of Bonanzas, Cessnas, and Bellancas—aircraft the Eagle outpaced in races above Midland oil fields.

During the final spin test, a company pilot had to bail out—with Federal Aviation Administration inspectors watching. Ted and Bob Windecker re-engineered the struture, lightening the tail and increasing its effectiveness in spin recovery. (All three brothers had by now taken on engineering and management positions.) In December 1969, it won certification as the world’s first all-composite airplane.

Aviation magazines declared it a game-changer, with a sticker price within $500 of a Beech Bonanza’s. But the board of directors rejected an aviation analyst’s recommendation to sell $20 million of stock to fund mass production, instead selling a mere $4 million worth. When the money came in, the board diverted most of it to other purposes.

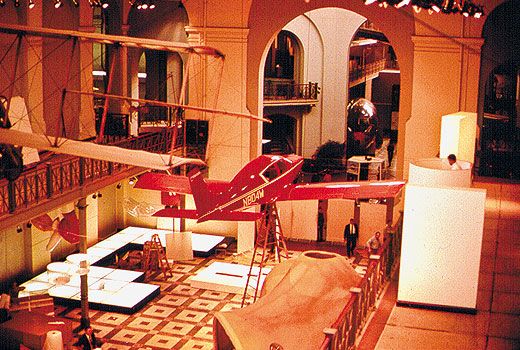

Leo Windecker returned to research. “Keeping an engineer in marketing and production never works,” he told me in 2006. To boost the Eagle’s radar reflectivity for civilian airport operations, he planned to install non-structural metal components. Now he sold Pentagon officials two radar-slippery non-metallized versions. Designated YE-5 by the Air Force and code-named CADDO by the Army, the stealth forerunner vanished into classified evaluation. Meanwhile, a skeleton crew in Midland hand-made about one Eagle a year: Build one, sell it, build another.

In 1974, visions of mass-produced Eagles returned. Lehman Brothers, one of several refinance offers, proffered a $20 million bailout with one stipulation: The renamed Windecker Industries had to file protective Chapter 11. But Blakemore vowed his name would never be associated with bankruptcy, Ted says. Lehman Brothers moved on. After just nine airplanes, so did the Windeckers. “It was a fantastic venture,” Dan Black says wistfully.

Today, general aviation’s best seller is Cirrus’ all-composite SR22. Leo Windecker lived to see it all and wasn’t surprised. “Aluminum,” he told me in 2007, “was never a very good material to build airplanes out of anyway.” In April 2009, Ted acquired the Eagle’s type certificate from Composite Aircraft Corporation, which had owned it since 1977. “We are raising capital to return an updated Eagle to the market,” he says.

Stephen Joiner writes about aviation from his home in southern California.