Karachi to Bombay to Calcutta

The struggle to start Air-India.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Karachi_to_Bombay_to_Calcutta_11-01-11_4_FLASH.jpg)

Like many things in India, civil aviation was subservient to the monsoon. Since the rains, which begin mid-June, have typically abated by early September, the subcontinent’s first regularly scheduled airmail service was to have been inaugurated on September 15, 1932. But that year, the rain and lashing wind persisted, making the Juhu airfield, Bombay’s first airport, a quagmire. In those days, the field was little more than a dried mud flat on the Indian Ocean coast, north of what was then the city center, and in what is now the hub of India’s famous film industry, Bollywood. It took another month before the airfield dried out enough to permit the first flight of the new service, a venture that would grow into Air-India, the national carrier.

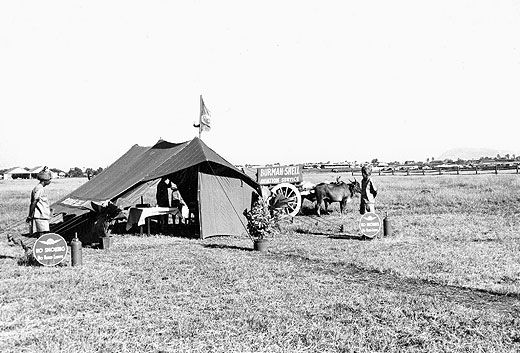

That it started at all was due to the persistence and vision of a tycoon and adventurer named J.R.D. Tata. In 1932, the 28-year-old industrialist cut a dashing figure. With his tidy mustache, trim frame, and pomaded hair, he looked like Errol Flynn. Finally, in October, after three years of lobbying the British colonial government, Jehangir Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, known to millions of Indians today as J.R.D., boarded a second-hand Puss Moth at Drigh Road airport in Karachi (in what is now Pakistan) for the flight to Bombay. Equipped with only a pair of goggles and the slide rule he used for navigating, J.R.D. took off with 120 pounds of mail. He stopped as planned in Ahmedabad, the halfway point in the 600-mile journey. “I was fuelled by Burmah Shell out of 2 gallon tins brought to the airfield in a bullock-cart,” J.R.D. remembered, according to materials in the Tata archives. “My only thought was to be on my way as quickly as possible so as to reach Juhu on schedule…and I managed to take off after 20 minutes in Ahmedabad after a lemonade and a brief talk to the press.”

The flight to Bombay (today, Mumbai) was “bumpy and hot” but otherwise uneventful, except for what an internal Tata Group review of the founding of the airline describes as the “killing of a bird which flew into the cabin of his machine.”

LAST YEAR, I visited Air-India Tower, the company’s headquarters in South Mumbai, and was surprised to see that J.R.D. Tata, who died in 1993, retains a large presence in the company. His picture adorns the walls of many offices, his office furniture is still in use (and treated like sacred relics), the screen savers on most computers scroll inspirational Tata quotations, and a bust of the man guards the building’s main doors. Kamaljeet Rattan, the airline’s spokesman, told me that when VIPs or high-ranking government employees call, their visits always begin with a ceremony during which the statue is given a flower garland, a tilak (a daub of sandalwood symbolizing the third, or mind’s, eye) is applied to his forehead, and Hindi devotional songs are sung. (Never mind that Tata wasn’t himself a Hindu.)

Employees who remember working with J.R.D. describe him as a saintly presence, in whom the staff was in awe. They recall him speaking quickly but quietly, with a slight French accent, and being prone to philosophical asides. They recount feeling sadness when Prime Minister Morarji Desai unceremoniously sacked him in 1978, without providing a reason.

Longtime Air-India executive Surendra Gupte told me he thought of J.R.D. “like a god.” He wasn’t kidding; under the glass on his desk were three pictures: two of the Indian god of knowledge, Ganesh, the other of J.R.D. Tata. Gupte remembers J.R.D. as a man who, while boarding an Air-India flight, refused to jump the queue; someone not afraid to take a meeting at his house in his pajamas or get under the hood of a troublesome automobile or put a reassuring hand on the shoulder of a young executive—things that would be anathema to the typical status- and class-obsessed Indian tycoon.

He wasn’t a pushover, though, according to Captain D. Bose, an Air-India pilot who served as the airline’s managing director from 1984 to 1987 and now chairs the J.R.D. Tata Trust. Bose says Tata “suffered no fools,” and would not hesitate to cut down an employee with a caustic remark for saying something J.R.D. disagreed with.

“He took a minute interest in the airline,” said Bose. “When he was on a flight, he would walk up and down the plane with his notebook and later write me letters outlining his suggestions. I remember once he asked me to research when we should serve the cheese course in first class. He wasn’t sure what to do because he said the French served it after dessert, but the Italians served it in between dinner and dessert.”

“His main characteristic was humility,” said Gupte. “And he led by example. Even after he was sacked, he held no grudge at all. His burning desire was that the airline would thrive and retain its past glory. The most amazing thing about him was his love for the airline. It was his baby.”

J.R.D. WAS THE SON of Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata (R.D.), who was a relation of Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, the founder of the so-called House of Tata. Jamsetji was a Parsi, one of some 110,000 Indian Zoroastrians, whose ancestors fled Persia and settled in Gujarat (now a state in western India) more than 1,000 years ago. Jamsetji made his fortune in textiles and weaving, but soon branched out. In the generations before J.R.D. ascended to the chairmanship of the Tata Group, the company established India’s first iron and steel companies, a hydroelectric power company, and the Indian Institute of Science.

Born in Paris in 1904 to a French mother, the young J.R.D.—“Jeh” to his friends and family—spent summers in Hardelot, in northern France. One of the Tatas’ neighbors was Louis Blériot, the Frenchman who in 1909 would make the first airplane flight across the English Channel. Blériot built a hangar on the beach, and J.R.D. found an early influence in Blériot test pilot Adolphe Pegoud. “To me Pegoud was one of the bravest and most foolhardy men that ever lived,” Tata told R.M. Lala, his biographer.

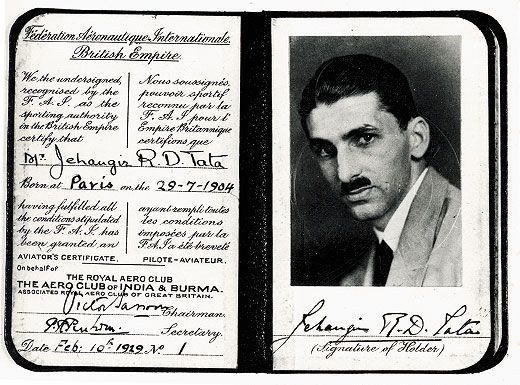

J.R.D. moved to Bombay in 1925, where he took an unpaid apprenticeship with Tata Group. (He ascended to the chairmanship in 1938, a position he held until 1991, overseeing the Tata empire in addition to retaining the chairmanship of Air-India.) When a flying club opened in Bombay, he got his pilot’s license in 1929, becoming the first pilot in India to do so, after only three hours and 45 minutes in the air. Of the achievement, he told Lala: “No document has ever given me a greater thrill than the little blue and gold certificate delivered to me on 10 February 1929, by the Aero Club of India and Burma on behalf of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. The fact that it bore the Number 1 added to my pride in owning it.”

A year later, Tata participated in the Aga Khan Prize race, in which the Muslim leader offered £500 to the first Indian to fly solo from England to India or vice versa. Tata took up the challenge, flying a Gipsy Moth from Karachi to the airfield at Croydon in England, by way of Basra, Gaza, Cairo, Tripoli, Naples, Rome, Marseilles, and Paris. His competition was a Sikh, Manmohan Singh, and an 18-year-old pilot named Aspy Engineer, who would later become the chief of staff of the Indian air force, and who won the race.

THE TATA NAME is everywhere in India. In Mumbai it’s on cars, trucks, billboards, and skyscrapers. The Tata Group has subsidiaries dealing in virtually every commodity: automobiles, mobile telephones, steel, shoes, life insurance, fertilizers, salt, bottled water, lentils. About the only thing they don’t have anymore is an airline.

In the nationalized airline Air-India, the visible record all but expunges the Tata name—and J.R.D.’s legacy. “Today’s Air-India pilots are not thinking about J.R.D.,” Bose said. “When I was flying, J.R.D. was a constant presence. As a young man, you’re busy with your flying and your career. They don’t have time to reflect on the airline’s founder.”

The leafy Tata “campus” in Pune, about 110 miles east of Mumbai, is a company headquarters that, among other things, serves as a training compound for hospitality workers in Tata hotels, the flagship of which is the Taj Mahal Palace, the luxury hotel adjacent to the Gateway to India in Mumbai. At the Tata Central Archives there, I found early Tata Air Lines documents, among them a 1933 speech Tata gave about air travel to the Bombay Rotary Club.

“Up to the end of 1929,” Tata told his audience, “apart from a few experimental flights, commercial aviation proper could have been suitably described by a zero so far as [India] was concerned. Considering the relatively advanced stage which air transport had reached by then in most of the other countries of the world, it may be asked why India of all countries should have been so conspicuously backward. Were there any obstacles in the way peculiar to India with which other countries were not handicapped?”

Never one to mince words, Tata answered his own question: “Lack of vision and initiative on the part of Government.”

India, Tata believed, was ripe for a service to fly mail and passengers. “Climatic conditions (for the greater part of the year), nature of the ground, distances, inadequacy of railways and roads, keenness of the people are all in her favour,” Tata told the Rotary Club.

J.R.D.’s partner in the new venture was Nevill Vintcent, a South African aviator and former Royal Air Force pilot. Born in 1902, Vintcent was a pugilist and an early proponent of flight in India, flying all over the subcontinent in the 1920s as a surveyor and barnstormer. In fact, it was Vintcent who took a proposal for an Indian airmail service to the Tatas. “I have tried to stress the fact that if Tata Sons are given this route it will give a great fillip to commercial flying in India,” Vintcent wrote of his negotiations with the government in a 1931 letter to J.R.D. “If the route is state operated I maintain that it will effectively put a stop to any further efforts by private firms to develop other routes, as they will argue that after the spade work has been done, the state reaps the benefit. I also maintain that private enterprise will develop flying far more quickly than the state can hope to do, and will consequently provide more openings for Indians in this profession.”

In March 1929, just six weeks after J.R.D. received his license, Tata Sons Limited (as the conglomerate was called then), with Vintcent as a partner and chief pilot, submitted to the colonial government its first proposal for establishing a regularly scheduled airmail service to peninsular India. Tata Aviation Services would extend the existing service, which Imperial Airways, the precursor of British Airways, provided from England to Karachi. There at Karachi, the Tatas’ airline would collect the mail and fly it to Bombay and Madras (now Chennai). One of “two single engined American planes”—according to an internal Tata Group history—would connect with Imperial Airways in Karachi once a week, weather permitting, and fly to Bombay, a journey that would take around eight hours, compared with nearly 45 hours by rail.

The entire airline would consist of two airplanes, two pilots, and two ground engineers, one “apprentice” (meaning an Indian) engineer, four coolies, and two chowkidars, or guards. And all of this for the government investment of just 100,000 to 125,000 Indian rupees (worth about $680,000 today), the bulk of which J.R.D. said would be recoverable through the extra airmail postage. Still, the government pleaded poverty.

Despite the Depression-induced austerity, the British government was keen to open the subcontinent to airmail service. At the time, the French Air Orient Company operated a service between Marseilles and Saigon, and the Royal Dutch Line’s KLM was operating between Holland and the Dutch East Indies. Due to government restrictions that J.R.D. found “incomprehensible,” mail bound for India and Burma was permitted to be carried by both of these services only as far as Karachi, where it was loaded onto a train bound for Calcutta, even though the aircraft were also bound for Calcutta.

Finally, Tata and Vintcent made an offer the British couldn’t refuse, offering to start the airline at almost no cost to the government. On April 24, 1932, Tata Air Mail was born, with the signing of a 10-year contract. The deal involved no government subsidiary, only a small stipend per pound of mail carried. Under the agreement, Tata Aviation Services would get free use of government aerodromes, but if the service was infrequent or unreliable, it could be cancelled. Furthermore, Tata Aviation Services was required to employ British subjects and use British airplanes—so much for the “American” aircraft. Tata and Vintcent bought another Puss Moth, this at a time when other civil air transport services were already using four-engine Armstrong Whitworth Atalantas.

After landing at Juhu on that first flight, the mail that was to continue to Madras was transferred to the second Moth, flown by chief pilot Vintcent, who spent the night in Bellary (about 500 miles away) before continuing on to Madras, on south India’s east coast. An internal history says simply: “This marked the beginning of the Indian air transport.”

IN 1933, ITS FIRST FULL YEAR of operation, Tata Aviation Services flew 160,000 miles, ferrying 23,800 pounds of mail and freight and 155 passengers on the Karachi-Bombay-Madras route. In 1936, the company introduced Waco biplanes, and in 1937 added service to New Delhi. The next year it was renamed Tata Air Lines.

In 1940, Nevill Vintcent traveled to England to meet with Lord Beaverbrook, who asked Tata Sons to supply the Ministry of Aircraft Production with 200 Tiger Moth training airplanes. Vintcent headed to the de Havilland factory in Canada to learn how to produce the aircraft; when he returned to India, Tata Sons built a factory at their own cost. A few months later, the Ministry of Aircraft Production decided it didn’t want Tiger Moths, and asked Tata Sons to build 400 Horsa gliders instead. Vintcent headed back to England to make preliminary production arrangements. On the return flight, his bomber was shot down and he was killed. Several months later the ministry sent a telegram to Tata Sons cancelling the Horsa contract.

Despite the devastating loss of Vintcent, the airline expanded after the war, when J.R.D. entered a partnership with the Indian government, which bought a 49 percent stake in the airline, with an option to buy another two percent. In 1953, citing a policy of nationalizing all transport services, the Socialist-leaning government exercised the option, and the airline was nationalized.

J.R.D. RETAINED the chairmanship of Air-India until 1978, but nationalization never sat well with him. In a 1953 telegram to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, he wrote that the “nationalisation scheme is not sound and will not result in the creation of an efficient and self supporting air transport system…. [And] I can only deplore that so vital a step should have been taken without giving us a proper hearing.” (For his part, Nehru noted in a letter J.R.D. Tata’s “evident distress” on learning that nationalization had taken place.)

“He had enormous popularity throughout his own country and the world in the early 1970s,” said the late R.E.G. Davies, former air transport curator at the National Air and Space Museum. “He was well respected in the industry at a time in which aviation services were almost entirely dominated by European and U.S. airlines. He managed to lead an indigenous Asian airline into the top ranks, and the recognition he received was both technical and social. Technical, because the Air-India fleet was always modern and competitive. Social, because thanks to the efforts of him and [then Air-India commercial director] Bobby Kooka, the onboard service was both elegant and efficient—and very Indian. At the heyday of Air-India, J.R.D. Tata was one of the most respected and adored leaders of any airline in the world.”

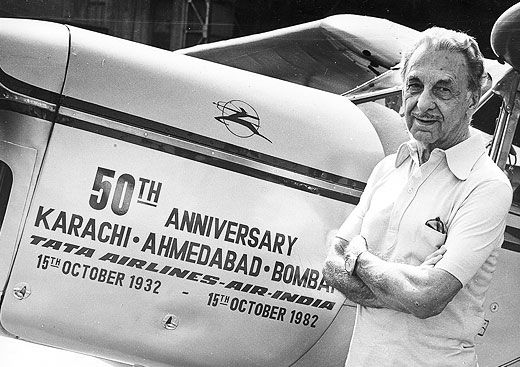

ON OCTOBER 15, 1982, 50 years to the day after Tata Aviation Services’ inaugural flight, a 78-year-old J.R.D. Tata, dressed in the light blue safari suit that had become his late-period trademark, took off from Drigh Road in Karachi in a Leopard Moth (a suitable Puss Moth couldn’t be found) bound for Bombay to commemorate the birth of Indian civil aviation.

J.R.D. had appointed Captain Bose to organize the flight. Bose remembers the board meeting in which Tata announced that he wanted to reenact the journey. “There was silence all around,” Bose said. “No board member dared open his mouth, but we all thought it was a dangerous idea,” given J.R.D.’s age.

Bose was charged with finding the airplane, then coordinating with de Havilland on its refurbishing. “Once this was done,” said Bose, “he didn’t want anything to do with me. He wanted to be in total control of the flight, and he didn’t want to be made to feel that he was in any way incapable of handling it himself.” In fact, Surendra Gupte, who worked closely with J.R.D. on the 50th anniversary celebrations, told me that J.R.D. confided to him before the flight that he had recently suffered a mild heart attack and that his doctor advised him against making the flight.

Afterward, J.R.D. told reporters that this flight too was uneventful.

“Ten minutes before the scheduled hour of 4 o’clock,” according to an account published in the Bombay newspaper Mid-Day, “Mr. J.R.D. Tata’s Leopard Moth was sighted over Bombay. But being a stickler for punctuality, he hung on over the horizon till the appointed hour.

“Then he came over the old Juhu airport and, like any other young daredevil airman, he swooped low over the [tent] holding some 1,500 invitees…. Then, taking a full circle, the Leopard Moth made a perfect three-point landing.”

When asked by reporters after the flight why he did it, J.R.D. expressed sentiments echoing the ones that led him to form India’s first and most enduring airline. “I felt rather shaken that in recent times there was a growing sense of disenchantment in our land,” he said, a possible reference to the country’s stalled economic development at the time. “There was a loss of hope, aspirations, and enthusiasm and a fall in morale amongst our youth. This flight, I hope, will rekindle a spark of enthusiasm and the desire in them to do something for the good of our country.”

Today’s Air-India passengers may join in J.R.D.’s wish. The carrier has fallen on hard times of late. Its legendary cabin service and punctuality is in decline; a delivery of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner has been deferred because of lack of cash; and the company is in talks with banks, hoping to restructure 200 billion rupees of debt. The elegance for which Air-India was once known has faded.

David Shaftel, a writer from New York City, now reports from Mumbai, India. His last article was “Brooklyn’s Jewel: Floyd Bennett Field” (Oct./Nov. 2010).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Karachi_to_Bombay_to_Calcutta_11-01-11_1_GALL.jpg)