Katharine Wright’s Knickers Too Risqué To Be Exhibited

Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit and the Barefoot Bandit’s pilot handbook also are among the items that museums can’t—or won’t—show you

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131029024050Wrights.jpg)

Harriet Baskas likes going to small museums that don’t get many visitors—collections of lightbulbs, hoards of Barbie dolls, piles of nuts. In these kinds of places, Baskas writes in her new book Hidden Treasures, “the volunteer on duty is apt to follow you around.” She often asks her minders to point out their favorite items. Sometimes, the best stuff isn’t on display; perhaps the artifact is too valuable, or extremely fragile. Or maybe it’s not on view because it is too politically or culturally sensitive.

Baskas uncovered many of these hidden treasures for a 26-part NPR radio project, which she’s now turned into a book. Of course we had to find out if she included anything aviation-related. And she did!

These pantaloons were likely worn beneath the dress Katharine Wright wore to the White House in 1909. Photograph: International Women’s Air & Space Museum, Cleveland, OH.

First up: Katharine Wright’s knickers. As Baskas writes, “Katharine was sometimes referred to as the ‘third Wright Brother,’ yet her life story and her role in the birth and growth of aviation has been generally overlooked. The collection at the International Women’s Air & Space Museum in Cleveland, Ohio, includes a dress that Katharine wore to the White House in 1909 when her brothers received the Aero Club of America award, as well as a pair of knickers. Only the dress is on display. “If we were an Edwardian museum or a fashion museum, the knickers be used in an exhibit,” collections manager Cris Takacs is quoted as saying. “We have not displayed them, in part because there are still some members of the Wright family around.”

If Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit goes back on display at the National Air and Space Museum, it would be in a special, climate-controlled case. Photograph: Mark Avino, NASM.

Next: Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit. The Apollo suits, says Baskas, were designed “to withstand temperatures of plus or minus 150 degrees Fahrenheit, radiation, and the possible penetration of particles traveling up to 18,000 miles an hour.” But they weren’t meant to last more than six months. Neil Armstrong’s spacesuit was displayed at the National Air and Space Museum almost continuously from 1973 to 2001, she writes, but was removed due to concerns about damage from humidity and light. It now lives in a cold vault at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia.

Unless you work for the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), you won’t be able to see this artifact. Photograph: Harriet Baskas.

Third on our list: The metal detector that screened terrorists at the Portland, Maine, airport on the morning of September 11, 2001.

The detector is now in the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) headquarters building in Washington, D.C., and isn’t meant to be part of a public tour. “TSA historian Michael Smith says that’s partly because his department has only two staff people,” Baskas writes, “but it’s mostly because the main goal of the project is to share the history of the agency with the TSA workforce, which now includes more than 50,000 people at more than 400 airports across the country. ‘A lot of people…they were just teenagers when it happened,’ says Smith. ‘So it’s important to tell that story to all of our employees.’”

At the time of the 9/11 attacks, Baskas writes, all of the screening equipment was owned by the airlines. “Delta Air Lines owned the Rapiscan machine the terrorists walked through in Portland, and after 9/11 the FAA pulled that machine off the line.” Eventually Delta put the machine in storage, where it remained until 2005, when the airline donated it to the TSA.

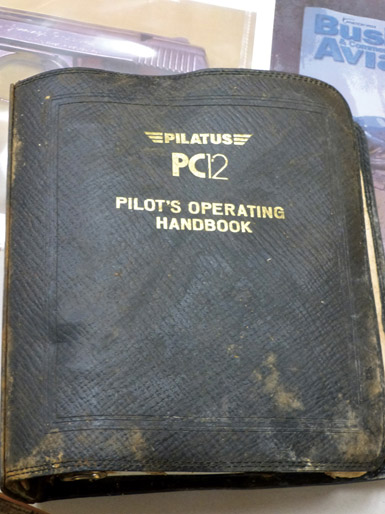

The “Barefoot Bandit” taught himself how to fly, in part, by using manuals he ordered online. Photograph: Harriet Baskas.

Last on our list is Colton Harris-Moore’s—aka the “Barefoot Bandit”—pilot’s operating handbook. Baskas notes that Harris-Moore became famous during “a multiyear crime spree that stretched from Washington state’s San Juan islands to Canada and the Bahamas and included dozens of burglaries and break-ins and the theft of cars, boats, bikes, and planes.” Harris-Moore was sentenced to seven years in state prison. In November 2012, the local sheriff’s office on Orcas Island called the Historical Museum and asked if they’d like multiple boxes of evidence from the trial. Included in the boxes were the pilot’s flight manuals that Harris-Moore used. The museum asked for input from the community on whether the items should be put on display, Baskas notes, as many of the locals were victims of Harris-Moore. Eirena Birkenfeld, the museum’s former community outreach coordinator, told Baskas “On the one hand is the fact that Colton Harris-Moore is now part of Orcas Island history. His presence dominated the island for many months. On the other side is the feeling that we shouldn’t be giving him any more notoriety.”