Two showmen, one dirigible, and the flight that changed aviation

Kings of the air.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Kings-of-Air-631.jpg)

At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, a seven-month-long world’s fair celebrating Thomas Jefferson’s epic real estate deal a century earlier, more than 19 million visitors were treated to exhibitions of wonders from across the country and around the world. Underwritten by $15 million in stock purchases and federal and state funding, the fair was, in the words of one newspaper headline, “The Most Stupendous Entertainment the World Has Ever Known.” Not only did it host the 1904 Olympic games, it also featured an aeronautic competition, with a $100,000 grand prize. That’s how the first public, powered flight in the United States came to take place in St. Louis before thousands of witnesses and how international aeronautical celebrity wore, for a time, a distinctly American face.

Two faces, actually: “Captain” Thomas Scott Baldwin and Roy Knabenshue. Beginning with just a handful of flights in a rickety dirigible, they helped change the course of flight itself. Without them, Glenn Curtiss, Lincoln Beachey, and many others might never have flown, and the Wright brothers’ career would have taken a different turn. The introduction of flight to most of the country, and much of the world, might have been delayed by years. As Baldwin and Knabenshue hustled their way through the sky, their adventures changed lives and fortunes.

In 1904, Europeans appeared to lead the way in human flight. The exploits of aviation pioneers Otto Lilienthal, Alberto Santos-Dumont, and Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin were well known in the United States. Americans, on the other hand, weren’t offering much in the way of aeronautical success. December 1903 brought headlines ridiculing the catastrophic failure of Samuel Pierpont Langley’s Grand Aerodrome, and unreliable reports of secretive brothers from Ohio and their apparently successful flights on the North Carolina coast.

The press heavily favored Santos-Dumont to win the grand prize at the St. Louis fair. Headlines blared from Paris of the Brazilian’s stunning successes with dirigibles, like his epic circling of the Eiffel Tower. If anyone could navigate the fair’s 30-mile grand prize course—three times around a 10-mile L-shaped path—it would be Santos-Dumont. But it was not to be. After arriving in St. Louis to great fanfare, Santos-Dumont’s airship No. 7 was left overnight in the fair’s aeronautical concourse hangar. The next morning the silk envelope was found irreparably slashed. The sabotage was never solved, and Santos-Dumont returned to Paris.

The field was now wide open for the grand prize. Several tried, but none made it past the 30-foot-high fence surrounding the concourse, ostensibly there to shelter the airships from the wind. Twenty-nine-year-old Roy Knabenshue witnessed the whole disappointing spectacle. He was selling tethered balloon rides that offered spectacular views of the fair. To attract business, he once allowed the balloon to rise while hanging onto its tether underneath. Sliding along as he and the balloon rose, he paused now and again, hanging on one-handed hundreds of feet up, waving to the growing crowd below.

Knabenshue was an unlikely daredevil. The son of a respected newspaper publisher in Toledo, he had a job installing switchboards for the telephone company. But after seeing balloon ascensions at state fairs, he had to fly. He bought a balloon and hit the circuit. To save his family shame, he adopted the moniker Professor Don Carlos.

Knabenshue quickly learned the century-old entrepreneurial rigors and the quasi-science of carnival ballooning. (He once tested, with nearly fatal results, his theory that ascending directly into a thunderstorm—in a balloon filled with highly flammable hydrogen—would be safer than staying on the ground.) By the time Knabenshue got to the St. Louis fair, he was looking for a new attraction to land contracts. He found it when it walked up and said hello.

“Captain” Thomas Scott Baldwin needed no introduction. Everything about him was big: his size, his demeanor, his career. For years, he had been the greatest showman among American aerialists. Baldwin was a tightrope walker and trapeze artist, often performing stunts dangling beneath a rising balloon. Wearing a pink leotard with blue trunks, he gained international fame in 1887 with his first parachute jumps. The parachute’s shroud lines ended in a small iron ring that Baldwin simply held with his hands. Earning a dollar for every foot he dropped, he would step out of his balloon’s basket and hold on tight. He strongly cautioned against changing one’s grip on the way down.

Baldwin’s parachute act took him to Europe, South Africa, New Zealand, and Asia. Somewhere in his adventures, he became “Captain” Tom. Always looking for his next act, Baldwin became interested in the flights of Santos-Dumont, and began his own experiments with steerable balloons—dirigibles. His search for a powerful, lightweight motor ended in Hammondsport, New York, at the workshop of a young motorcycle manufacturer named Glenn Curtiss.

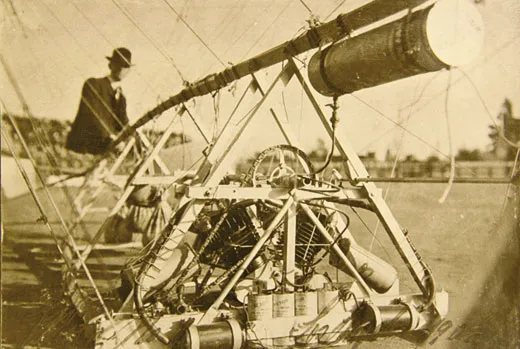

In August 1904, Baldwin completed his first airship back home in San Francisco, and gave the inelegant craft a decidedly ambitious name, perfect for advertising: the California Arrow. With a net covering an oblong, hydrogen-filled silk bag, it looked like a giant captured potato. Underneath was slung a triangular wooden frame that held the Curtiss engine, a rudimentary propeller, and the pilot. It was an acrobat’s machine. Although it had a rudder for steering, the pilot controlled pitch by making his way forward and backward along the frame. By the time Baldwin tested the ship, Santos-Dumont’s misfortune in St. Louis was old news. Baldwin arrived in St. Louis on September 10, 1904, with only the bag and the motor. He was in luck. The deadline for the grand prize had been extended to the end of October, and he needed to build a new frame. Soon after he arrived, he recruited the slender, lightweight Knabenshue to be the pilot. At 220 pounds, Baldwin was 100 pounds too heavy; the Arrow couldn’t lift him.

The two men built the frame and propeller, then inflated the bag. Six days before the deadline, they launched.

On October 25, 1904, the Arrow was taken out into the concourse. Knabenshue climbed aboard, and the Curtiss motor was started. It shook the frail frame violently. “I longed for a piece of rubber to put between my chattering teeth,” Knabenshue recalls in his unpublished autobiography. He yelled at Baldwin to get a mechanic, but Baldwin misheard and ordered the ad hoc ground crew to let go. Flying straight at the hangar, Knabenshue tugged the rudder and swung around—directly toward the dreaded fence. Heaving over some ballast, he watched the fence slip by underneath. America’s first public dirigible flight was under way.

With the motor spewing flame and black smoke, Knabenshue climbed, threading his way among the domes and spikes of the fair’s ornate palaces. Narrowly missing the giant Ferris wheel, he swung out over the grounds as tens of thousands cheered and gaped—someone at St. Louis was actually flying! And then it was over. The Curtiss coughed and died, and Knabenshue began to float east. He crossed the Mississippi and landed in a cornfield in East St. Louis. He missed the course altogether, but he, Baldwin, and the Arrow were heroes.

The newspapers roared. “Airship Arrow Scores Triumph!” “Aeronaut Knabenshue is Now Hero of the World’s Fair!” The flights continued until early November. Knabenshue thrilled the crowds with turns, circles, figure eights, and landings back at the concourse. Memories of failure evaporated, but sadly, so did the grand prize. Baldwin was awarded only $500 for demonstrating “dirigibility.”

It didn’t matter. Newspapers from New York to the Yukon trumpeted the pair’s success. The American public no longer needed Santos-Dumont nor anyone else from overseas for aerial heroes. Knabenshue and Baldwin headed for California, and for the next four years, the one-man dirigible owned the American sky.

Their partnership did not last long. The two turned in a set of stunning flights in Los Angeles: in one, Knabenshue was filmed in what he claimed was the first movie ever shot in the city; in another, he entered a race to Pasadena with the owner of a Pope automobile and won. Having earned nationwide fame, Knabenshue and Baldwin parted ways in the spring of 1905.

***

Returning to Toledo, Knabenshue quickly crowned himself King of the Air. He built two new airships, and instantly made a splash for his hometown crowd by landing on the roof of the Spitzer building. As he traveled all over the country, headlines followed his adventures, including a flight up Broadway and a landing in Central Park, a dawn flight around the Ohio state capitol in Columbus, Henry Ford’s personal offer to provide a new engine clutch (and go into business together), and a nearly suicidal high-wind flight in Brockton, Massachusetts. Knabenshue was carried around on a lot of shoulders.

Baldwin went to Portland, Oregon, for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. Still too heavy for his airship, he hired a short, athletic teenager he’d known from San Francisco to be the pilot: Lincoln Beachey. The young pilot’s precocious skill and daring made him the star of the show. It was Beachey’s first taste of fame. He would go on to help design a dirigible known as the Beachey-Baldwin, and thrill millions with his exhibition flying. Beachey would die in 1914, in a monoplane accident at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

Baldwin accumulated success for the Arrow, but he hit a snag, then a catastrophe. First, Professor John Montgomery of Santa Clara sued him, alleging he stole secrets that made the Arrow fly; then the 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck, and he lost everything.

A calamitous natural disaster was nothing for Tom Baldwin. He moved to Hammondsport and started over with Glenn Curtiss. Perhaps no one was more affected by Baldwin and Knabenshue’s success. Overnight, they had converted Curtiss into an airship engine builder, and his reputation was growing. Curtiss had exhibited at the Aero Club of America’s show at the New York Armory in 1906, where he caught the attention of Alexander Graham Bell, who was looking for motors for his nascent aerial experiments. And because of Baldwin, Curtiss met the Wright brothers.

In the fall of 1906, Baldwin was flying his California Arrow II at the Dayton fairgrounds. Curtiss was there as a mechanic. It was not exactly a coincidence. Curtiss wanted to sell motors to the Wrights. They met when the Wrights came to see Baldwin perform (and even joined a rescue party when the Arrow escaped its mooring). The Wrights invited Baldwin and Curtiss to their Dayton shop and showed pictures of their Flyer. Although Curtiss initially saw aviation as a new market for his motors, his personal interest in flying grew. In June 1907, with Baldwin’s encouragement, he flew one of Baldwin’s ships for the first time. A few months later, Bell invited him to join the Aerial Experiment Association (AEA) to pursue heavier-than-air flight. Curtiss was on his way to the airplane.

And the airplane was on its way to the public. The Wright brothers had already triumphed, privately, and were approaching a public debut. In the meantime, Santos-Dumont briefly recaptured headlines when he hopped his first airplane, the 14-bis, in Paris in 1906. The heroes of St. Louis stuck with the dirigible as long as they could. There was still plenty of business. It wasn’t always easy, as Knabenshue discovered when he attempted to launch a team. With four new ships and novice pilots, he set out in 1907 with $425,000 in pending contracts. But he later noted, “With partly or poorly trained pilots I hoped to collect this money. My banker must have been a very patient and believing man….” In one day, two of his pilots crashed and destroyed their ships, and Knabenshue’s own ship exploded. He struggled through the rest of the season, then disbanded his team.

Meanwhile, Baldwin convinced the U.S. Army that a dirigible would be a sound investment, and he was awarded a contract for the military’s first powered flying machine. Curtiss built the motor, and together they arrived at Fort Myer, Virginia, to conduct tests in public. On August 4, 1908, the two made their first practice flight. But four days later, Wilbur Wright flew before an audience of thousands in Le Mans, France, and everything changed.

Curtiss and the AEA had actually built and flown three airplanes by that time, and Curtiss had even won the Scientific American trophy for a straight-line, one-kilometer flight. Henry Farman of France had flown a kilometer in a crude circle. (In their 1905 private flights in Dayton, the Wrights had flown 38 times that distance.) But at Le Mans, Wilbur’s sweeping, banking turns and figure eights—plus the Wrights’ revolutionary propeller—placed the brothers far beyond anyone else in the air.

The Wrights had done it. With paying customers, and a patent to boot, the airplane had truly arrived, and the Wright brothers now owned the sky.

***

Knabenshue, Baldwin, and their dirigibles reunited in St. Louis for the city’s centennial in October 1909, but competed for attention with Glenn Curtiss, who was flying his Gold Bug biplane, having just won the first Gordon Bennett Cup race, held in France. The gasbag’s last stand came in January 1910 at Dominguez Field in Los Angeles (see “The Big Race of 1910,” Dec. 2009/Jan. 2010). Knabenshue and Beachey vied valiantly for attention as Curtiss and French aviation enthusiast Louis Paulhan sped past them and overwhelmed the crowd.

As aviation moved rapidly ahead, Knabenshue and Baldwin did too. Baldwin set up shop in New York and designed his own airplane: the Red Devil. He went back on the road as an exhibition pilot, even returning to Asia. Knabenshue became the Wright brothers’ exhibition team manager. It didn’t last long. The deadly business dried up after less than two years, and Knabenshue started over. He built a non-rigid dirigible capable of carrying 13, and launched a passenger service in Los Angeles, then Chicago. Both ventures failed.

World War I engulfed them all. Baldwin joined the Connecticut Aircraft Company to build airships for the Navy, then ran the Curtiss training facility in Newport News, Virginia. In 1917, he was commissioned as an actual captain in the Army Signal Corps. From Akron, Ohio, he supervised the inspection of all airships and balloons coming out of the United States. He left the service with a promotion to major and a stable job at Goodyear.

Knabenshue struggled. He failed to sell his passenger airship to the Navy but continued to promote dirigibles. He devised elaborate schemes for Zeppelin-like passenger airships—even passenger service to Hawaii. Finally, he went to work for the National Park Service, spearheading aviation projects (including the purchase of the service’s first airplane and autogyro). But as his health failed, he was practically exiled to White Sands, New Mexico. When he retired, he had to plead for a meager pension.

Baldwin died suddenly of a heart attack on May 17, 1923; he was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

Knabenshue faded away, living quietly with his wife in a trailer park outside Los Angeles. Every now and again, he’d resurface in the press, and once on national television. Ever the entrepreneur, he tried selling his story to Hollywood. He even tried to get back in the air, building a reproduction of one of his early ships. He was denied permission to fly. But Orville Wright remembered Knabenshue. On the 40th anniversary of the 1904 St. Louis flight, he sent Knabenshue a telegram saying, “Don’t you remember it, and doesn’t it give you a thrill when you think of it?” Knabenshue died in poverty on March 6, 1960.

Paul Glenshaw is director of the Discovery of Flight Foundation and co-producer of the 2009 documentary Barnstorming. His last article for Air & Space, “Inches to Go” (Dec. 2012/Jan. 2013), reported on a University of Maryland team’s effort to build and fly a human-powered helicopter.