Kursk

The greatest tank battle in history might have ended differently had it not been for the action in the air.

:focal(5426x1760:5427x1761)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/7a/e17aa30a-5868-4d5a-ad79-6758240c49b1/07c_am2015_kurskopener_live.jpg)

So stupendous was the clash of armies around the Soviet city of Kursk in July 1943 that until recently historians focused almost exclusively on the actions of the famous Panzer groups and Red Guard units—German and Soviet tanks, artillery, and infantry—that fought the exhausting, weeks-long battle. But at the end of the first day of combat—July 5—Soviet premier Josef Stalin was focused on another contest that he knew would affect the outcome of the battle for Kursk. He called on one of his commanders, Konstantin Rokossovsky, for an account of the day’s action, but before Rokossovsky concluded his report, Stalin interrupted: “Do we have control of the air, or not?” Rokossovsky could only promise that tomorrow they would.

At Kursk, both sides believed that ground forces alone could not win the day, and for the first time, each relied on masses of aircraft specially designed or equipped to destroy tanks. Both German and Soviet attack aircraft flew combat missions at the request of frontline units and were controlled by ground liaison officers attached to armored forces.

Key to the German effort was the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka, a gull-wing, two-place dive bomber that, at its most effective, punched through defenses with 37mm cannon mounted on pylons beneath its wings. Although a leftover from the Spanish Civil War—and with fixed landing gear, slower than most other aircraft in the sky—the Stuka was a dangerous weapon, especially in the hands of ground-attack experts like Hans-Ulrich Rudel. Rudel was a phenomenon. He logged more than 2,500 combat missions during the war and is credited with the destruction of more than 500 tanks and 700 trucks.

Even in the hands of merely competent pilots, the Stuka, sometimes loaded with two 110-pound bombs beneath the wings, instead of the anti-tank cannon, and a single 550-pound bomb beneath the fuselage, was extremely effective against armor. British test pilot Eric “Winkle” Brown picked the Stuka as the best dive bomber of the war. The commanding officer of a group evaluating captured aircraft, Brown had flown dozens of Axis and Allied types, and in his 1988 book Duels in the Sky, he ranks them. The Stuka was “in a class of its own,” he writes, rating it ahead of the U.S. Douglas Dauntless and Japanese Aichi Val. “It’s the only one that you can dive truly vertically.” At Kursk, the Germans had 400 of them.

For all its destructive power, however, the Stuka had little defensive armament and couldn’t survive without protection. Even Rudel was shot down 32 times (though all by ground fire) and wounded on many occasions, once so severely that part of his right leg had to be amputated. Thereafter, he flew with a prosthetic limb.

The Stukas were joined by armadas of Junkers Ju 88 and Heinkel He 111 medium bombers, all acting as long-range artillery. The twin-engine Henschel Hs 129 also helped provide close air support—but not very much; its two weak engines required constant maintenance.

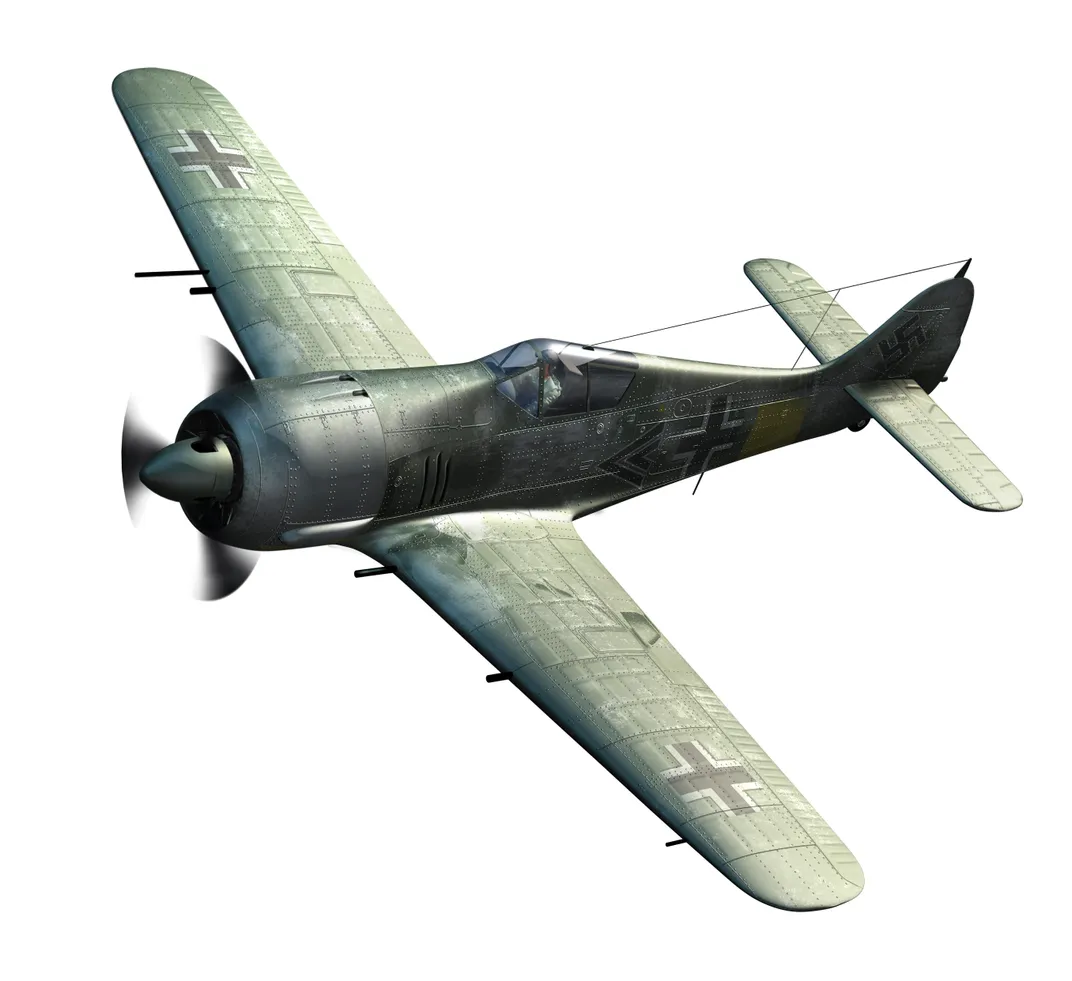

At Kursk, the job of protecting the German bombers fell mainly to Messerschmitt Bf 109 G and Focke Wulf Fw 190 fighters. These were almost evenly matched against Soviet Yaks and Lavochkins. The German fighters were slightly more advanced, but the Soviet fighters had the advantage in numbers. The real disparity between the two sides lay in the experience of the pilots. Although in January 1943 the Soviets had instituted a new tactical training program, in which pilots practiced combat maneuvers and methods of attacking small, mobile targets, the German pilots had had more effective practice: years of aerial combat. One German fighter squadron the Soviets faced included 11 pilots who had scored aerial victories; one of them, Joachim Kirschner, was credited with 148. On the first day of combat at Kursk, he made it 150.

In the Soviet corner, Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik dive bombers were aided by sturdy Petlyakov Pe-2s, less numerous but more maneuverable than the heavily armored Ilyushins. The Sturmoviks were known to the Soviets as “flying tanks,” partly because of the armor—as much as 2,000 pounds of it—encasing its forward fuselage. The rear fuselage, on the other hand, was made of wood. Later models of the Il-2 flew with rear-facing gunners, who, unprotected, suffered four times the injuries and deaths that pilots did.

In his memoir, pilot V.S. Frolov recalls surviving an attack after his airplane was struck: “I was unconscious for a moment, then felt a jet of cold air burst into the cockpit. Opening my eyes, I pulled the control stick and leveled out from a dive just above the tree tops. I shot a glance back and saw an enormous hole in the wing root and the fuselage…. There was no response from the gunner.” Frolov nursed the Il-2 back to base, but as he approached the aircraft began to disintegrate. When it struck a shelter it broke apart. Frolov, covered in blood, was dragged from underneath the cockpit wreckage. His gunner was dead.

Sturmoviks were equipped with 37mm cannon as well as rocket and grenade launchers. The bomber could also dispense small anti-tank bombs. With 192 armor-piercing bombs in four cartridges, the Sturmovik would fly over tank formations, releasing a bomb every 20 yards and blanketing a 3,500-square-yard area with fire. The frontline Sturmovik force at Kursk was more than 750 strong.

The Eastern Front

When Hitler launched his armies against the Soviet Union, in June 1941, the first operation was an air strike against Soviet airfields. Caught by surprise, the Soviets lost 1,800 aircraft by the end of the first day, and 4,000 by the end of the week. German forces then roared 600 miles east, reaching Moscow and fighting until winter set in, forcing retreat. The following year, a second offensive brought German soldiers to Stalingrad, but after a long, infamous siege, a Soviet counterattack resulted in the surrender of 100,000 soldiers of the German Sixth Army. If nothing else, by the end of Stalingrad, the two sides had proved they were willing to absorb titanic losses.

The Germans made their third assault, Operation Citadel, in the summer of 1943. During post-Stalingrad fighting, the Soviets had driven a wedge into the German line west of Kursk (see map, opposite). Citadel was planned as a pincer assault, with one army commanded by General Walther Model driving south from Orel, and another, commanded by Field Marshall Erich von Manstein, pushing north from Belgorod. The two were to meet at Kursk, thereby encircling and destroying Soviet forces in the bulge. Informed by British intelligence sources, the Soviets knew the tanks were coming and where they would strike.

Learning a lesson from the Germans, the Soviet air force began attacking German air bases in April. The first strike destroyed 18 vital Junkers Ju 88 and Dornier Do 17 photo-reconnaissance aircraft. Between May 6 and 8, the Soviet air force flew 1,400 sorties against 17 German-controlled airfields and railways, destroying 300 rail cars in three ammunition trains. A third air operation, from June 8 to 10, hit 28 airfields and claimed the destruction of more than 500 German aircraft. An exaggeration? Unquestionably. Both sides exaggerated numbers in this battle, but the attack destroyed enough key airplanes to impair Luftwaffe reconnaissance.

In the meantime, as Germans waited for tank deliveries, the Soviets dug trenches, strung barbed wire, laid landmines, built tank traps, and positioned the heaviest concentration of gun emplacements in the history of warfare.

With reports that the Soviets would strike on July 5, the Red air force took to the air long before dawn. From four airfields, 84 Sturmoviks launched, hoping to hit German fighters at their bases near Kharkov in Ukraine. But at the same time, the Soviets had also begun an artillery barrage, and to counter it, the Luftwaffe had been dispatched to bomb the gun emplacements. The Soviet dive bombers ran smack into the German fighters. For many Soviet pilots, this was their first combat mission; some had less than 30 hours of flight time. The Germans easily sliced through the Red air force formations, but Luftwaffe fighter escorts were diverted from their planned mission to protect Stukas and strafe ground troops. Instead they had to defend their own airfields against Soviet bombers and attack aircraft.

Shock and Awe

As hundreds of tanks hammered at one another, German infantry and Panzer divisions, supported by Ju 87s, pushed forward. Bomb-carrying Stukas rolled in directly above anti-aircraft artillery sites. In vertical dives, the Ju 87 pilots kept airspeed under control by deploying air brakes. To prevent the aircraft from colliding with their released bombs, a U-shaped “crutch” shoved the bombs clear of the propeller. Pullout was automatically controlled.

A typical attack on a tank was wholly different. The dive began at an angle of five to 10 degrees and at just over 210 mph. “Our ‘cannon planes’ took a terrible toll of the Russian armor,” recalled Ju 87 radio operator Hans Krohn in a 1987 book of personal accounts collected by F.S. Gnezdilov. “We attacked at very low altitude—I often feared that we were going to hit a ground obstacle with our landing gear—and my pilot opened fire at the tanks from a distance of only 50 meters. That gave us very little margin to pull up and get away before the tank exploded, so immediately after the cannons were fired I always prepared myself for a very rash maneuver. At the same time, in that moment I had to be very watchful because in this area the Russian fighters were very active and they sure were most serious adversaries!”

From airfields to the east, Soviet Sturmoviks, both the extremely vulnerable single-seat version as well as the improved two-place model—joined the battle in great numbers. In July 1943, the Soviets had deep reserves; more than 2,800 Il-2s were available. They were needed. Sturmovik losses were heavy and gave rise to a tactic known as the Circle of Death. As many as eight Sturmoviks would arrive over a target and establish an orbit. The dive bombers would take turns attacking targets with bombs, rockets, and cannon, rejoining the circle to provide defense. Wing-mounted machine guns made it possible for each pilot to defend the aircraft ahead of him. The tactic gave less experienced Sturmovik crews a fighting chance, but the Soviets were more than willing to trade one for one.

In the dawn hours of opening day, the Germans dominated the air over the front with waves of fighters sweeping the skies clear of Soviet aircraft, while German bombers pounded opposing armored columns below. By 7 a.m., however, as the Panzers advanced, swarms of Soviet fighters and attack aircraft joined the fray. With tanks and armor clashing below and airplanes raining from the sky, black smoke engulfed the battlefields, turning day into night.

To the men in the tanks and trenches at Kursk, it became an appalling war of attrition. In the Soviet archives, authors David M. Glantz and Jonathan Mallory House found descriptions of the battlefield for their 1999 book The Battle of Kursk. One Soviet veteran reported, “It was difficult to verify that anything remained alive in front of such a steel avalanche…. Acrid gases from the exploding shells and mines blinded the eyes. Soldiers were deafened by the thunder of guns and mortars and the creaking of tracks.”

The most grueling assignment of all, however, was flying in the rear gunner position of a Stuka or Sturmovik. The gunners sat facing backward as the world around them turned into a gruesome panorama of tracers, flame, and smoke. One gunner at Kursk, Sergeant Erwin Hentschel, eventually accumulated over 1,300 missions with Hans-Ulrich Rudel. By the end of Citadel, Rudel, with Hentschel defending him, claimed to have destroyed more than 100 tanks. No matter how inflated the claim, one must give credit to Hentschel for having ridden through at least that many harrowing attacks. Both Rudel and Hentschel were awarded the Knight’s Cross, one of Nazi Germany’s highest awards for bravery.

According to Soviet records, by the end of the day on July 5, Luftwaffe pilots had shot down 250 aircraft, 107 of them Sturmoviks. Luftwaffe logs indicate 74 German airplanes lost. Perhaps because of Stalin’s question to Rokossovsky, Soviet bombers harassed German positions all night, depriving the exhausted troops of sleep. The Germans were unable to mount a similarly tormenting nighttime effort.

Turning Point

As the battle progressed, the Soviets changed tactics. On July 7, they massed their Sturmoviks and fighter cover into formations of 30 or more. The numbers overwhelmed German interceptors. During the exchanges, Soviet Yak-1s shot down Stuka pilot Kurt-Albert Pape, a Knight’s Cross holder with over 350 missions. On July 8, German ace Hubert Strassl, with 67 claimed victories, was lost. Stuka pilots Karl Fitzner and Bernhard Wutka, both with Knight’s Crosses and 600 missions each, were shot down and killed. The Germans were losing irreplaceable veterans, while the Soviets were stifling Panzer ground advances.

Each night, the Soviets analyzed the day’s results and adjusted. They allowed the pilots flying fighter cover more independent action. Flights were split and arranged in echelons by altitude. Fighter groups were allowed to roam ahead freely over German-held territory in sweeps similar to the German tactic. The turning point in the air contest came on July 9, days ahead of positive results on the ground. Soviet fighters decimated the Stuka ranks. Sorties by the Ju 87s dropped to about 500, half of the opening day’s total.

Coincidentally, that morning, Ivan Kozhedub, flying an La-5, spotted two Messerschmitt Bf 109s positioning for an attack. Kozhedub turned head on toward the leader. “I was the first to shoot,” he recalled. “I held the firing button, squeezed and blasted away a long burst, and it was sufficient! The leader turned over from his steep dive and I saw him hit the ground.” The leader was legendary ace Günther Rall, who had 151 claims. Rall survived the crash landing and was back in the air that afternoon.

As mechanized units surged, then withdrew, confusion reigned. In early morning fog, a Soviet tank unit plunged into the deep trenches dug to stop German tanks. On July 12, a Heinkel He 111 bomber attacked the 11th Panzer command group on the north bank of the North Donets River, the bomber crew believing the group to be Soviets. Two staff officers died, and the Sixth Panzer Division commander, General Walther von Hünersdorff, and 12 other officers were wounded.

The same day, the Soviets began Operation Kutuzov, a counterattack intent on trapping the German forces fighting in the Orel bulge. The assault was halted at Khotynets by German aircraft, saving two armies from being surrounded. General Model sent a telegram to the German high command: “For the first time in the history of the war, the Luftwaffe, without the support of ground troops, deprived the fighting ability of a Russian tank brigade.”

Though halted, the Soviets fanatically defended every square foot. Intense German air support was required to move even the slightest distance forward. In one instance, the Soviet 200th Tank Brigade withstood 12 attacks by massed Panzer tanks and relentless

air attack; only after suffering grievous losses did the brigade pull back a short distance.

By the end of the first week of the campaign, Luftwaffe sorties began to drop off sharply due to attrition and fuel shortages. Meanwhile, Soviet sorties increased. The commander in the south, von Manstein, repeatedly asked the German high command for reinforcements, but two months before, Allied forces in Tunisia had taken a quarter of a million German soldiers prisoner, and no reinforcements were sent. On July 12, seeing the small gains made at Kursk—and the great cost—Hitler instructed his commanders to withdraw. The following day, Hans-Ulrich Rudel wrote in his diary, “Not many words are spoken in our Gruppe during these days, only what is most important is said. The severity of the struggle is weighing heavily on all of us. It is the same situation in all other units.”

Aircraft, tank, and personnel losses at Kursk have been subject to much dispute, but given each side’s own accounting, it is possible to list at least these losses: The Germans record 194 aircraft and 280 tanks lost. The Soviets acknowledge losing 1,130 aircraft and between 1,600 and 1,900 tanks. The Germans suffered 56,000 casualties; the Soviets, 177,000. In some ways, Kursk looks like the war as a whole: As many as nine million people in Germany died; the Soviet Union lost 24 million.

By the end of July, Operation Citadel was over. The Soviets had gained air supremacy and went on full offense…all the way to Berlin.