No Twin Mustang Has Ever Been Restored…Until Now

Last of the long-distance escorts.

:focal(2511x1562:2512x1563)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/8a/ab8aef18-6d79-4277-b2ad-a61ddfc01e25/14a_fm2020_a_slocum_xpanddoc3_live.jpg)

As I walked into a hangar belonging to the Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum in Titusville, Florida last March, I ran into a familiar sight: a B-25 Mitchell bomber named Panchito. By some stroke of kismet, it was the same B-25 I had seen five years earlier as a reporter in Georgetown, Delaware, where I wrote about the bomber’s role as a mascot for a local boys’ baseball team.

The restored bomber was in Titusville to participate in the Space Coast Warbird Airshow. Sitting next to the B-25 was the man who had restored it, Tom Reilly. For the last 48 years, Reilly has restored 34 aircraft, including nine B-25s (counting Panchito).

“There are two types of people—bomber pilots and fighter pilots,” Reilly told me. “The fighter pilots always wear clean clothes. They don’t have any oil dripped on them. They don’t have any cuts. Bomber guys have grease on them.” Of the two camps, Reilly is firmly grounded among the bomber guys. His blue jeans are streaked with grease, and his hands show dirt and signs of sun damage, no doubt from years spent working outdoors in Florida.

In 1971, Reilly was working as a skydiving instructor in Kissimmee when he took a chance ride in a P-51 Mustang. The next day, he jumped into the airplane business. He bought four North American NA-64 Yales in Canada and doubled his money when he sold them. Since then, he has restored a B-24 Liberator, a P-40 Warhawk, nine T-6s, three Boeing B-17s, and the aforementioned B-25s.

A master restorer, sporting a baseball cap emblazoned “Tom Reilly Warbird Restoration Museum” with his signature stitched on the right side, Reilly can be brusque. Without knowing his impressive history, one could easily consider him arrogant. Once you get to know him, though, his kindness is apparent.

“He can be intimidating at times, and he can be an absolute sweetheart,” says Louisa “Weezie” Barendse, Reilly’s dogged researcher. She has scoured online sources for drawings and aircraft parts. “After a while, he expects you to not ask stupid questions,” she says. “He’s very serious when it comes to working on the airplanes.”

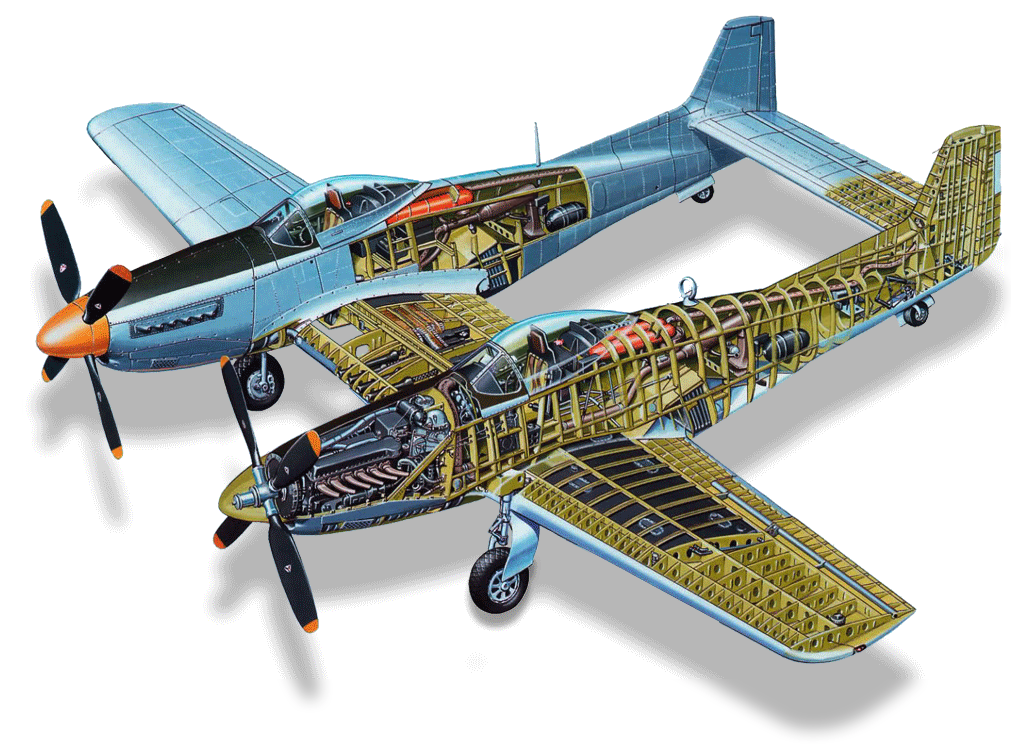

Reilly’s latest undertaking might be his most challenging: a North American XP-82, the second prototype—but the first to fly—of the U.S. Army Air Corps’ Twin Mustang. Invented by German-born aircraft designer Edgar Schmued and greenlit by the U.S. Army Air Forces’ General Hap Arnold in 1943, the Twin Mustang is unique: It mates two North American P-51 fuselages with a common center wing and a horizontal stabilizer. Schmued’s double aircraft could accommodate a two-man crew, which would lighten workload and reduce pilot fatigue—a necessity for the airplane’s expected long-range missions. In February 1947, Colonel Robert E. Thacker flew a P-82B nonstop from Hawaii to New York without refueling. The 5,051-mile flight is the longest nonstop flight ever made by a propeller-driven fighter.

The P-82 arrived too late in World War II for its original mission as a bomber escort in the Pacific, but it performed a crucial, if short-lived, role in the Korean War: flying combat patrols over the 38th parallel. Before its ultimate retirement in 1953, the aircraft, which had been redesignated as the F-82, would also fly ground-attack missions in South- and North Korea.

The rarity of the Twin Mustang has only increased. Of the 272 manufactured by North American, Reilly’s is one of five remaining and the only surviving prototype. (Only two prototypes were built. The first prototype was scrapped at Maryland’s Naval Air Station Patuxent River in 1953.) His is currently the only P-82 in flying condition, though that distinction came unexpectedly when test pilot Ray Fowler accidentally flew the fighter on New Year’s Eve 2018 over Reilly’s airfield in Douglas, Georgia.

“It was cold, and we wanted to put a little bit of air underneath the wings just to test the stick,” says Reilly. “It had so much horsepower, and it accelerated so much faster than a regular D-model Mustang, which is usually what [Fowler] flies” that it became airborne before Fowler intended it to.

While aviation geeks rejoiced over the resurrected fighter’s unintentional flight, the occasion marked only one step in a long journey that involved a global scavenger hunt. Reilly boasts that he can rebuild anything, but tracking down the Twin Mustang parts posed the greatest hurdle of the project. When he describes his quest, he reiterates one word: magical. “It became an incredibly magical project where virtually everything went perfectly right, all at the right time,” he says.

The XP-82’s rising originated where many warbird restoration stories begin: in the backyard of the late Walter Soplata, who had amassed a junkyard collection of aircraft at his farm in Newbury, Ohio. When Reilly found the first piece of the Twin Mustang puzzle, the fighter was in bad shape. The second prototype had lived a full and bruising life as a test aircraft for the Air Force and later the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (the predecessor to NASA). The XP-82’s run with NACA lasted from 1946 until 1949, when the aircraft skidded off an icy runway. With a twisted fuselage and bent propellers, the XP-82 was damaged beyond repair when it was acquired by Soplata, who proceeded to hack away at its inboard section and unbolt its wings.

The XP-82 would remain in a sad state until December 2007, when Reilly was picking his way through Soplata’s snowy yard as he surveyed the collector’s aircraft for an IRS appraisal. Reilly turned over a piece of tin to reveal what he assumed was a P-51 fuselage, but Soplata told him it was the left fuselage of an XP-82.

The sight was almost mythical for Reilly. He had seen an F-82 decades earlier, and despite his affinity for bombers, had fallen in love with the Twin Mustang and longed to purchase one. It’s now become his favorite aircraft. “It was just sleek, and it was different I guess,” he says. “I had seen all the fighters in the world, but I had never seen one of these.”

Reilly purchased the left fuselage, and then pooled the contributions of 40 investors—without revealing to them which airplane he intended to restore. He knew that if word got out that an XP-82 was available, other warbird collectors would pounce.

“It’s one of the last warbird projects to buy,” says Reilly. “There’s no B-17s. There’s hardly any Mustangs. There’s no Corsairs. No P-38s—none of these projects exist any longer. Everything that was out there has been gobbled up.”

His clandestine search brought him to a wreck in Alaska, where he found an F-82 tail section and outboard wings. In Colorado, Reilly bought a badly damaged right fuselage and had his team copy the bent pieces. He also procured 40,000 pages of plans for the XP-82 (through the E model F-82) from a collector in California who had preserved the blueprints by transferring them from microfiche to DVDs.

Perhaps the most unexpected gem he unearthed was the P-82’s lefthand-turning engine. Reilly’s aircraft, the first prototype to fly, initially had upsweeping props: the left fuselage had a counter-rotating lefthand-turning engine (a Packard V-1650 Merlin). The right fuselage had the standard righthand turner. (Only one flight was ever made with this configuration.) The Merlin engines would go on to power the initial production models until failed contract negotiations with Rolls-Royce forced the Air Force to switch to the Allison V-1710 for later versions of the Twin Mustang. The Merlin engine, though, produces an appealingly throatier sound than the Allison.

Unable to track down the elusive lefthand-turning engine, Reilly decided to negotiate for an engine core that could be rebuilt. Just as he was writing the check, he got a call from Mike Nixon, an expert restorer of Merlin V-12 engines in California. Nixon had discovered a never-used Merlin lefthand-turning engine sitting in a garage—in Mexico City. “I said, ‘Buy it,’ ” says Reilly. “Didn’t even ask the price. How this one spare got to Mexico, we have no clue and we’ll never know.”

As Reilly widened his search for parts and word leaked out that the XP-82 might come together, he began receiving donated parts from well-wishers, including a canopy from North Carolina and a rare automatic-direction-finder radio crank from England. “It’s such a rare airplane,” he says. “It’s not a Mustang, it’s not a Corsair—it’s an XP-82. It’s rare. So people are sending me stuff.”

The attention to detail on Reilly’s XP-82 is stunning, down to the brass mount for the aircraft’s fire extinguisher and the original World War II radios that include a detonator switch designed to explode the radios in the event of a crash and capture by the Germans or Japanese. Only a few of Reilly’s modifications prevent the XP-82 from being a perfect replica. For example, he has installed MT composite propellers for lack of steel ones made by Aeroproducts.

“You’re doing your best to roll the clock back, and some things you just can’t,” says Bill Parks, a mechanic who is part of the XP-82 restoration team.

For parts that can’t be purchased or salvaged, Reilly’s machinists, Vick Paris and John Eiler, stepped in. A native of Jackson, Michigan, Eiler is retired after working three decades as a tool-and-die maker in the automotive industry. He joined the XP-82 team eight years ago. Since then, he has machined more than 300 parts for the aircraft along with his son, John Eiler Jr., who programs the machines on a computer. “They’re new parts, but made exactly like the original,” says Eiler senior. “You couldn’t tell mine from the original one.”

The team’s commitment to originality paid off: The XP-82 took home four awards at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s 2019 AirVenture in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, including the Phoenix Award, which Reilly received for restoring an airplane that was considered beyond help.

Maintenance on the XP-82 has proven demanding since few Twin Mustangs exist and Reilly has already drained the world of parts, says Max Hodges, a volunteer mechanic on the XP-82. Hodges is also an experienced commercial pilot, and he got the opportunity to fly the XP-82 from the right seat alongside test pilot Ray Fowler leading from the left.

During the flight, Hodges experienced the same disorienting effects of flying a double aircraft that earlier Twin Mustang pilots withstood. In his book, Twin Mustang: The North American F-82 at War, author Alan Carey writes: “From an operational standpoint, some pilots felt a psychological discomfort of impending doom of a mid-air collision when they caught sight of the co-pilot/radar operator’s fuselage out of the corner of their eyes.”

The XP-82’s bewildering complexity, from its scarce parts to its unsettling effect on pilots, might be part of the appeal for Reilly. Back out on the airfield in Florida, Sharon Mason, who worked as Reilly’s office manager at his former warbird museum in Kissimmee, greeted Reilly under the wings of Panchito. The two worked together on B-25s as well as on a B-24 Liberator, a rotted bomber that had served as a coastal aircraft in India. In that case and with the XP-82, Reilly welcomed the task of putting together an aircraft when others said it couldn’t be done. “He’s drawn to a challenge,” says Mason. “He says, ‘I’m going to do it.’ ”

The XP-82 might be Reilly’s greatest challenge to date, but it’s likely not his last.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/00/a70007f4-8c4d-4919-8859-75ffaa029abd/14j_fm2020_c_paulshootingrandallbuckingrivetsonwing_live.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/bc/13bce666-39ca-40d4-9cfc-de5f4082cb13/14v_fm2020_g_face1cropped_dsc0777_live.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/48/464853e8-0eae-429b-9673-10511014aa73/14g_fm2020_b_xp-82naca_live.jpg)