Last Men Out

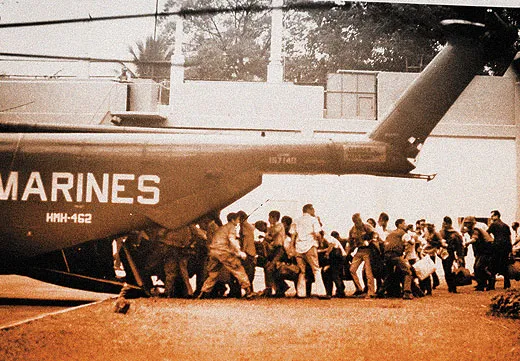

As Saigon fell, a small band of Marines pulled off the final evacuation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Last_Men_Out_11-01-11_1_FLASH.jpg)

During America’s final 24 hours in Vietnam, the Marines battled time, weather, and miscommunication to save as many people as possible. Saigon was about to fall, and the North Vietnamese army had cut off access to the coast, making a sealift impossible. A week earlier, when the provinces fell, foreign commercial air carriers ceased operations out of Saigon. Tan Son Nhut, the last friendly military airstrip, had been bombed, removing fixed-wing aircraft from the escape options. This story begins there.

APRIL 29, 1975. Major Jim Kean, commanding officer of Company C, gazed out the window of the abandoned secretary’s office on the second floor of the U.S. embassy in Saigon. The sky was the color of brushed aluminum, and the first of the cloud fortresses marching in from the sea had settled overhead. Kean, the ranking officer among the Marines remaining at the embassy, scanned the Marine Security Guard duty roster. He had 46 U.S. Marine security guards here in the embassy compound, 15 across town at the U.S. Defense Attaché’s Office, and the remains of two KIA on a slab at the Seventh Day Adventist Hospital somewhere in between.

Two years earlier, the Department of Defense, despite repeated public declarations of support for the South Vietnam government, had put into place secret plans for the emergency evacuation of Saigon. Although strategists had considered several options, the swift advance of the North Vietnamese army toward the city left only one alternative: a helicopter evacuation, code-named Frequent Wind, centered on the U.S. Defense Attaché’s Office (DAO) at the airport and the U.S. embassy. The embassy’s rooftop helipad was strong enough to support a Bell UH-1 Huey and, at least according to the engineers, an even larger and heavier CH-46 Sea Knight. The big Marine CH-53 Sea Stallions could use only landing zones on the ground.

A signal for the evacuation of Saigon had been worked out some weeks earlier: an announcer for the Armed Forces Radio would read the words, “The temperature in Saigon is 105 degrees and rising.” This code phrase was to be followed by a Bing Crosby recording of “I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas” playing continuously. The signal was known to all Americans, civilian and military, and thus to just about everyone else in the city.

The evacuation would take every chopper the Marines, Air Force, Navy, and Air America (a civilian airline operated by the Central Intelligence Agency) could muster.

AT 10:51 A.M. ON APRIL 29, 1975 —

13 years after the first American was killed in open combat with the enemy in Vietnam—Ambassador Graham Martin officially relinquished civilian control of South Vietnam and formally executed Operation Frequent Wind. It was now a military operation.

At 12:30 p.m., the first U.S. Navy A-7 Corsair jet attack aircraft and U.S. Air Force F-4 Phantom jet fighters, dispatched from bases in Thailand, crossed into South Vietnam airspace. Their mission was to provide cover for the initial wave of Marine Sea Stallions, Sea Knights, and Air Force Jolly Green Giants powering up on the deck of the Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Hancock and bound for the defense attaché’s compound at the airport. These squadrons, fielding a total of about 36 rescue helicopters, would also deposit a battalion of Fleet Marines as a show of force to secure the grounds.

Marine Brigadier General Richard Carey, in the communications room of the USS Blue Ridge, would oversee the evacuation. Once at the DAO compound, Carey reached Ambassador Martin by telephone at the embassy and asked how many evacuees remained.

The ambassador was hesitant to report specific numbers, yet managed to impart that the embassy evacuation had not proceeded according to plan. There were hundreds of people encamped on the grounds awaiting retrieval. Carey was floored. He was under the impression that the embassy, if not now emptied by buses, soon would be. There had been no planning for any major movements from that location. Carey radioed Admiral George Steele and informed him that an immediate adjustment in helicopter priorities was needed.

By now, the leading edge of the rain squalls had formed a curtain falling across the eastern edge of Saigon. The first wave of Marine pilots reported poor-to-zero visibility. Seventh Fleet air traffic controllers tracked the rain clouds on radar while simultaneously remaining alert for American craft straying out of the two predetermined corridors in and out of the city.

The Michigan corridor, at 6,500 feet, was reserved for inbound aircraft; the Ohio corridor, at 5,500 feet, for outbound. Soon enough, both pilots and air traffic controllers knew, the monsoon clouds would force their aircraft below the flight corridors and down into range of small-arms fire and rocket-propelled grenades.

Forty miles away, a light drizzle began to fall on the embassy compound. From the edge of the parking lot, Major Kean watched the helicopters overfly the embassy. He knew they were headed toward the DAO. Kean went inside and picked up the telephone, and was patched through to the DAO’s Colonel Alfred Gray. Gray told him that, as Kean suspected, General Carey and Admiral Steele had been under the impression that all but a skeleton staff had been extracted from the embassy by bus and convoyed to the DAO. Carey had scheduled only two airlifts for the embassy, to accommodate the ambassador and a small remaining Marine guard.

“I need choppers here, lots of them,” Kean said. He told Gray that in addition to the embassy staff, his Marines, and the 1,000-plus refugees already inside the walls, he was receiving estimates that there could be as many as 10,000 Vietnamese surrounding the compound.

Kean hung up and took an elevator to the roof. He found Master Sergeant Juan Valdez, the noncommissioned officer in charge, whom the men called “Top,” outside the incinerator room.

“Choppers on their way,” he said. Both men peered over the edge at the parking lot. “Fifty-threes down there”—Kean swiveled to check the helipad atop the incinerator room—“…-46s up here.”

IT WAS NEARLY 6 P.M. when Kean, on the embassy roof, heard the washboard thumping of the helicopter rotors in the distance. A moment later he spotted a flight of four Sea Knights banking hard and lining up in formation for successive descents. The Marines had already cordoned off four groups of refugees, each consisting of 20 to 25 people, and were herding them up the stairs to the roof for boarding on the empty CH-46s. Not long after, the CH-53s approached the parking lot.

The helicopters descended at 10-minute intervals. They found the top of the vertical tunnel, slowed their forward progress, hovered for an instant, then one at a time made the dizzying 70-foot drop as if hurtling down an elevator chute. If a helicopter crashed in the parking lot, there was nothing with which to move it, and thus no more choppers coming in.

There was less than an hour left before the sun went down. The pilot yelled: “How many left?”

“At least a thousand.”

“Fleet not gonna like that.”

Kean shrugged.

“I might be the last for a while,” the pilot said. “Deciding out there whether to fly after dark.”

Kean knew that even Marine pilots needed downtime. There was nothing he could say. He loaded the helicopter, watched it rise, and, once it had cleared the roof, saw the pilot jam his throttle forward as the helicopter curved out of sight, following the contours of the Saigon River.

As the sky turned black, Carey told Kean that as soon as the DAO evacuation was completed, the embassy would begin receiving CH-46s on the roof and CH-53s out of the parking lot. But as the twilight shadows lengthened, helicopter pilots descending into the embassy compound began encountering difficulties with visibility. The last few to make it in to the parking lot landing zone told Kean that Task Force 76 commander, Admiral David Whitmire, had ordered all CH-53 evacuations to cease at complete dark. They might be able to get on and off the roof, but there was no way they could chance a blind vertical descent to the parking lot.

Kean asked a CH-53 pilot to relay the message that he would have the parking lot lit up like Broadway, and ordered a squad of Marine guards to round up and fuel every vehicle remaining in the compound. Within 10 minutes, the landing zone was encircled by glowing headlights.

But by 1 a.m. the vectoring helicopter pilots were having difficulty making out the now-dimming headlights.

Dazed by fatigue, it took the Marines at the embassy some moments to realize that the whap-whap-whap of the helicopter rotors was no longer beating against their eardrums. Had the evacuation operation ended with hundreds of people still within the embassy compound? No one seemed to know. Out on the Blue Ridge, Carey reached the war room and confronted Task Force 76’s Admiral Whitmire.

Whitmire told him that on orders from “Washington,” he had grounded all flights out of concern for flight safety.

Carey tried to hold his temper. In a calm voice he noted to Whitmire that by the time the pilots had completed their mandatory rest time and got back in the air, the only soldiers left to greet them in Saigon would belong to the North Vietnamese forces fighting to take Saigon.

From ready rooms, chow lines, and bunks across a plethora of ships, pilots were summoned and ordered back into the air, and the first Marine squadrons began to ascend from the decks. Dawn, and all that it implied, was four hours away.

“Hear that?”

Master Sergeant Juan Valdez glanced from Major Kean to the sky and then to his watch. It was 2:15 a.m., and two Marine H-46s were vectoring over the embassy. Kean was already crouched on the helipad when the first Sea Knight descended. He ran to the cockpit, and the pilot leaned out the window and shouted.

“Nineteen more flights behind me, sir. That’s it.”

The major took a mental head count. There were at least 850 more evacuees scattered around the compound, not counting the 200 or so Marines, as well as a few remaining American civilians and other service members. More than 1,000 people did not divide into 20 helicopters. He knew there was no use arguing with the pilot. He would do the best he could.

At 3:30 a.m., Carey received a flash message from the White House. President Ford had grown tired of his polite requests being ignored, and his orders were succinct: he wanted Ambassador Martin out. Immediately. Moreover, no more Vietnamese were to be evacuated.

Captain Gerry Berry, piloting the CH-46 Lady Ace 09, and his wingman, Captain Klaus Schagat, had been in the first wave of Marines to pluck evacuees from Saigon. Since they’d lifted off from the deck of the USS Dubuque, they had flown 32 round trips into and out of Saigon in the 15 hours.

As Berry touched down on the embassy roof, he grabbed a grease pencil from his pocket and began to write on the frayed and creased laminated card on the clipboard strapped to his leg. The note read, “Ambassador Will Depart With Me. Now.”

Kean advised Berry that he needed confirmation. Berry’s crew chief handed Kean a headset; General Carey was on the other end. Carey told Kean that the order had come directly from the president. “All remaining lifts,” Carey added, “will be limited to U.S. and amphibious personnel.”

“General, my Marines are on the wall, and then there’s the front door of the embassy,” Kean began. “Between my Marines and that front door are some 400 refugees still awaiting evacuation. I want you to understand clearly that when I pull my Marines back to the embassy, those people will be left behind.”

Carey’s voice crackled over the air. “And I want you, Major, to understand that the president of the United States directs.”

As a dazed, hunched Ambassador Martin shuffled toward the helicopter, one of his bodyguards handed him the folded embassy flag. The ambassador stepped into the waiting Sea Knight. It was 4:58 a.m., April 30, 1975.

As Berry landed on the Blue Ridge, his crew chief’s voice came over the intercom.

“We going back in for those Marines?”

DESPITE THE RADIO conversation with Carey, Kean had not quite given up on the arrival of more rescue helicopters. After Berry’s CH-46 lifted off, he waited in vain for another helicopter.

“No more CH-53s,” Kean announced. “Just Americans now. Roof.”

Kean sprinted toward the Marine security guards. “On my signal we will withdraw calmly in a semicircle toward the embassy front door,” Kean told each squad leader. “No running, no shouting.”

They formed three concentric half-moons of about 15 men each. As the entire mass of Marines edged slowly backward, the 400 or so Vietnamese began to stir.

For one moment it seemed as if events were transpiring in slow motion. The Vietnamese stared blankly at the American troops as the outermost perimeter, its flanks collapsing in on itself, backed into the lobby. Perhaps half of the Marines in the second perimeter had made it inside before a giant roar drowned out even the sounds of artillery falling on the city’s outskirts.

“Here they come!” someone shouted, and the front gates gave way like matchsticks.

The Marines slammed shut the double doors and bolted them. They rode the elevators to the sixth floor, locked the power off, threw the keys down the shafts, then started for the stairwells. With the outside perimeter abandoned, it was now a race against time—a race against whoever would be next to storm up the embassy stairs.

Kean did the math. There were about 60 Marines and a few men from other services scattered about the rooftop. “I figure it will take three, maybe four runs at most,” he said to the men.

General Carey paced the deck of the Blue Ridge and read the cable in disbelief. Somewhere along the line, someone had misinterpreted Captain Berry’s coded transmission, “The tiger is out of his cage.” Instead of understanding that the ambassador had left the embassy, it was inferred that all Americans had been evacuated from Saigon. The airlift was now considered complete. The helicopters had been ordered grounded.

Frantic, Carey telephoned Lieutenant General Lou Wilson in Honolulu. “General,” replied Wilson, “I want you to inform the entire chain of command there of one important fact. I will personally court-martial anyone, regardless of service or rank, who halts any flights while Marines remain unaccounted for. Are you clear on that?”

Carey said he was.

It did not take long for hundreds of angry South Vietnamese to flood up the embassy stairwell, breaking the chain link barriers as they came. The Marines heard the gates crash, one by one, until the mob was directly outside the barricaded steel door leading to the roof.

In the distance, the Marines heard the beating rotors of a helicopter approaching. The poor souls in the stairwell heard it too. There was a brief pause in the pandemonium, and then the door’s hinges creaked and began to buckle.

As the first Sea Knight’s rear wheels bounced onto the helipad, the sky was the clear blue of watery ink, somewhere between night and dawn. The helo’s engine geared down, and Schagat, Berry’s wingman, leaned out and grinned.

Berry hovered above, waiting to take Schagat’s place. For a brief moment, as Berry gazed toward the southeast, he was certain that the sun had risen pocked with black dots, like a swarm of angry bees. He realized that the “bees” darkening the skies above the South China Sea were hundreds of South Vietnamese helicopters issuing from the coast and making for the fleet.

Schagat’s chopper was up and gone within 10 minutes. As Berry’s aircraft swooped down, Kean took another head count and turned to Valdez.

“Never get us all in,” Valdez said.

Kean looked around. “Top,” he said. “Give me nine guys I can bet my life on.”

When Lady Ace 09 was loaded and ready to lift off, Berry gave Kean the thumbs-up. The pilot was checking his control panel when the major walked to the cockpit. Berry pulled the headset from his ear and leaned out the window.

“Make sure you get back for us,” Kean said. “Don’t leave us here.”

In Washington, D.C., Secretary of State Henry Kissinger had been assured that Graham Martin had finally departed the embassy, on the last American helicopter to leave Saigon, and was now safe with the Seventh Fleet.

Now Kissinger had one final task: to face a press corps that, in his words, would go to any length to confirm “that everything that had ever happened [in Vietnam] had been an unforgivable mistake.” As he crossed the passageway between the White House and the Executive Office Building, he studied the statement he was about to read, the statement he was certain would be ignored. He would try to tell the newspeople that it was too soon for a postmortem on Vietnam, that the wounds to the country were still too raw. They would not understand. They wanted blood.

After Kissinger concluded his plea for a period of introspection, a reporter asked the question on everyone’s mind: “Mr. Secretary, there are reports that there are still Marines at the embassy in Saigon. Can you confirm that, and why are they still there?”

Kissinger, visibly flummoxed, could only stare at the upturned faces in the gallery. He turned abruptly and hurried from the podium. He found an aide and demanded a telephone. He needed to get in touch with the Seventh Fleet, or anyone who could confirm this horrible error. And then he needed to speak to the president.

THEY HAD ALL HEARD the stories about North Vietnamese prison camps. The Hanoi Hilton. The Tiger Cages. Staff Sergeant Mike Sullivan intuited the thoughts running through each man’s mind. It wasn’t supposed to end like this. Vietnam was supposed to be another Korea, a country divided in the middle, the southern half kept safe by an uneasy truce backed by American might. “Everybody bring it in,” he said.

One by one the Marines gathered about him. One asked, “You think the fleet’s even still out there?”

“Of course it is,” Sullivan said.

“I ain’t ending up in no camp,” said another, who motioned toward one of the machine guns. “I got my spot picked out.”

“We better take a vote,” Sullivan said. He had no doubt how it would come out. But he wanted to make it official.

One by one, each man voted to fight.

Kean looked over the rampart and checked his watch. It had been just over an hour.

Sergeant Terry Bennington, squatting behind his M-60, and Corporal Dave Norman, lying on his back on the helipad, spotted it simultaneously: a slender white contrail painting the blue sky far to the southeast.

“Major Kean.”

In the time it took Kean to raise his binoculars, the contours of the CH-46 became visible. Four Marine AH-Cobra gunships flew cover on the compass points— above, below, and to either side of the Sea Knight, criss-crossing in attack formation every half mile.

The sniping turned into a barrage as the chopper banked for its final approach and the CH-46 set its great black tires down on the rooftop helipad. Its crew chief dropped the tailgate. The glass in the side windows had been shot out.

Kean ran to the cockpit and shouted above the beating blades, “Waitin’ for you. Didn’t think you were coming.”

The Marine pilot, Captain Tom Holben, grinned and gave the thumbs up. The Cobra gunships, nose down for optimal firing, swooped like hawks above the embassy. High above them, a Navy A-7 Corsair attack jet left its own vapor trail in the form of interlacing circles.

Kean led the Marines up the ramp. “Pop the gas,” someone yelled, and Gunnery Sergeant Bobby Schlager pulled the pins on two canisters of tear gas. He rolled them out the gunner’s door. They hissed, tumbled off the helipad, and came to a stop.

It took a moment for everyone to realize the mistake. The rotors were sucking the gas vapors into the cockpit and the cabin of the helicopter. The pilots were blinded. The helicopter hopped and lurched, its skids bouncing once, twice, three times off the landing zone.

Through the fog, Valdez could just make out the door to the roof. It bulged, buckled, and then broke.

Holben and his copilot’s eyes were red with fatigue and the effects of the tear gas, but in a moment most of it had blown off. They could see if they squinted. Just as the mob surged up the outside staircase and onto the sun-baked roof, Holben lifted off.

During Operation Frequent Wind, which many referred to as the American Dunkirk, U.S. Marine helicopter pilots flew 682 sorties into Saigon. A total of 395 Americans and 4,475 Vietnamese and third-country nationals were evacuated from the U.S. Defense Attaché’s Office, with another 978 Americans and 1,220 Vietnamese and others rescued from the U.S. embassy. Altogether, more than 7,000 people were lifted out of the city before it was occupied by North Vietnamese troops and the Viet Cong.

Bob Drury has written two books with Tom Clavin (Halsey’s Typhoon and The Last Stand of Fox Company) and is a contributing editor for Men’s Health magazine. Tom Clavin is the author or coauthor of 11 books, and the former editorin- chief of The Independent, a weekly newspaper chain.